Jean-Léon Gérôme (French, 1824-1904) Evening Prayer

Lot 266

About Seller

Bonhams Skinner

274 Cedar Hill Street

Marlborough, MA 01752

United States

Founded over four decades ago, Bonhams Skinner offers more than 60 auctions annually. Bonhams Skinner auctions reach an international audience and showcase the unique, rare, and beautiful in dozens of categories, including the fine and decorative arts, jewelry, modern design, musical instruments, sc...Read more

Estimate:

$400,000 - $600,000

Absentee vs Live bid

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $10 |

| $100 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $3,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $30,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

| $300,000 | $25,000 |

| $500,000 | $50,000 |

| $1,000,000 | $100,000 |

About Auction

By Bonhams Skinner

Sep 21, 2018

Set Reminder

2018-09-21 14:00:00

2018-09-21 14:00:00

America/New_York

Bidsquare

Bidsquare : Fine Paintings & Sculpture

https://www.bidsquare.com/auctions/skinner/fine-paintings-sculpture-3427

Bonhams Skinner bidsquare@bonhamsskinner.com

Bonhams Skinner bidsquare@bonhamsskinner.com

- Lot Description

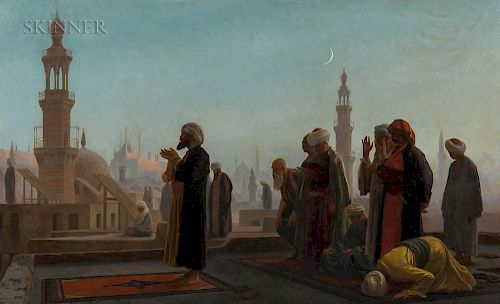

Jean-Léon Gérôme (French, 1824-1904)

Evening Prayer, or Prayer in the East

Signed "J.L. GEROME" c.l. along the edge of the wall of the roof, identified on a presentation plaque and on an encapsulated exhibition label from the Union League of Philadelphia (see below) affixed to the back of the frame, "BVC -19240-" inscribed in black ink across the center horizontal bar, and with a gummed label with the typed number "H-513" also on the back of the panel.

Oil on cradled mahogany panel, 19 1/2 x 31 7/8 in. (49.5 x 81.0 cm), framed.

Condition: Minor dots of retouch to sky, retouch to edges to cover frame abrasion, a treatment report from the Art Conservation Department, Buffalo State College, accompanies the lot.

Provenance: Sam Mendel (1814-1884), Manchester, UK, from at least 1 July 1870 until 22 September 1873 (known as Prayer at Cairo); Agnew's, London, from 22 September 1873 until 29 October 1873 (sold as Prayer at Cairo); to Henry William Ferdinand Bolckow (1806-1878), Middlesbrough, UK, in October, 1873 (known as Prayer in the East); by descent to Mrs. Henry William Ferdinand Bolckow in 1878; to Christie, Manson and Woods, London, Modern Pictures, May 5, 1888, as Lot 18 (sold as Prayer in the East); purchased from above by Goupil; to Boussod, Valadon & Cie. ("BVC - 19240") (sold as Prayer in the East); purchased from Boussod, Valadon & Cie. in New York by William P. Henszey (1832-1909), Wynnewood, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, on September 28, 1889 (known as Evening Prayer); through to M.M. Pochapin, President, Art Movement, Inc., New York (as Evening Prayer); purchased by W.G. Dickenson, Lockport, New York, March 16, 1945, from the National Hall of Art, Art Movement, Inc. (as Evening Prayer); then by descent.

Exhibitions: Royal Mining, Engineering, and Industrial Exhibition (International and Colonial), Newcastle-upon-Tyne, United Kingdom, 1887 (no. 905, as Prayer in the East), lent by Henry William Ferdinand Bolckow; Union League of Philadelphia, Loan Exhibition of Paintings by Eminent Artists Belonging to a few Citizens of Philadelphia, May 11-27, 1893 (no. 58, as Evening Prayer), lent by William P. Henszey; Union League of Philadelphia, Art Loan Exhibition, May 11-27, 1899 (no. 67, as Evening Prayer), lent by William P. Henszey.

N.B. A letter of authentication from Emily M. Weeks, Ph.D. will accompany the work. The painting will also be included in Dr. Weeks's revision of the artist's catalogue raisonné. We would like to thank Dr. Weeks for preparing the catalog note that follows immediately below.

In the 1860s, Gérôme began a series of pictures depicting Muslim men at prayer. These would become a signature theme of the artist's, and among his most popular Orientalist works. The present painting, Evening Prayer, holds a special place within this important group. A "perfected" version of one of Gérôme's most evocative compositions, with all of the technical hallmarks and intellectual nuances of his art, it has recently been confirmed as an original work by his hand, and returned to the artist's oeuvre. (1)

Gérôme's path to Orientalism began in 1856, when he traveled to Egypt for the first time. (Earlier in his career, he had made his name with light-hearted Néo-Grec genre scenes and archaeologically exacting images of the classical past.) In Cairo, he accumulated a virtual library of souvenirs, costumes, and local crafts, as well as photographs, sketches, and drawings, which served as inspiration for his studio works. Subsequent trips to the region made during the 1860s and 1870s expanded his repertoire of subjects, confirming his talents as an ethnographer and his reputation as a privileged witness to all aspects of Middle Eastern life.

In the present work, Gérôme depicts the daily maghrib, or evening prayer, performed on the housetops of Cairo. (2) In the background, the distinctive skyline of the city is visible, with the Mosque of Muhammad Ali and the Madrasa of Sultan Hasan helping to identify the geography of the site. (3) Gérôme's figures are executed with comparable documentary care: The men face east, towards Mecca, as the crescent moon and direction of the waning light suggest. They demonstrate each of the ritual postures associated with the prayer, from the initial standing qiyam to the last prostrate sajda. The motivation for this encyclopedic view was likely a favorite reference of Gérôme's: Edward William Lane's An Account of the Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians, first published in London in 1836, also described these poses, in pictures and in text. (4)

Despite these glosses of realism, Gérôme's image is far from true. A minaret from the Madrasa of the Amir Sarghitmish (1356), placed prominently on the left, should be miles from this scene, and the rooftop wind scoops are likewise curiously placed. (5) (To catch the prevailing winds that sweep through Cairo, they should be facing north.) Several of the men, moreover, inspire a strong sense of dejà vu. They reappear in others of Gérôme's compositions, in various contexts and dress. (6) Rather than a sign of ignorance, however, or a thoughtless oversight, these were deliberate choices by the artist, made for aesthetic effect. (7)

Such artistic liberty did not diminish the overall popularity of Gérôme's Middle Eastern works, nor jeopardize their worth. At least three painted versions of the present subject are known, and numerous reproductions and copies were made during the course of the artist's career - a testament to its success. (8) The original painting in the Hamburger Kunsthalle, exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1865, shares many of the same features with the present picture, including its formidable size. It is the differences between the two, however, that are most important here: In the present work, the absence of background figures and the substitution of a striking man in red - a favorite model of the artist's - serve to focus all attention on the devotions of the group, and the poetry of prayer.

In the nineteenth century, making versions of a favorite or highly coveted subject was the standard practice of many artists, and held a specific societal value. Those without the resources to purchase a popular Salon painting could, by these means, enjoy similar works in their own homes, particularly through the production of a reduction, or smaller version of the piece. (9) For those who wished for a grander addition to their well-hung walls, a répétition was the answer to their needs. This was understood to be a later version of a painting, of roughly the same size. Owing to a few compositional differences - a requisite of this type - the répétition was considered to be an original and costly work of art. As Patricia Mainardi explains: "The correct term for an artist's later version of his own theme . was . . . répétition, the same word used in performance for a rehearsal. In performance, we never assume that opening night is qualitatively better than later presentations - first performances are, in fact, usually weaker than subsequent ones, which gain in depth from greater experience and familiarity with the material." ("The 19th-century art trade: copies, variations, replicas," The Van Gogh Museum Journal 2000, pp. 63-4.). Evening Prayer, then, the last of the three painted versions of this subject to be made, and the only répétition that is known, may be interpreted as Gérôme's most valuable a - Shipping Info

-

Please visit http://www.skinnerinc.com/services/payment-and-shipping/ for information regarding the collection of items purchased at auction.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB