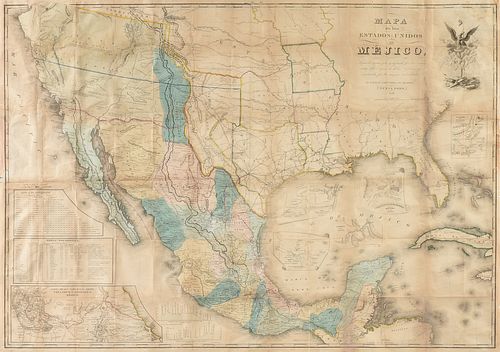

A LATE MEXICAN-AMERICAN WAR ERA MAP, "Mapa de los Estados Unidos de Mejico, Revised Edition," JOHN DISTURNELL, NEW YORK,1848-1850,

About Seller

6116 Skyline Drive, Suite 1

Houston, TX 77057

United States

Simpson Galleries has been serving Houston’s need for the very best in antique sales venues for more than fifty years. Beginning in 1962, William Simpson started educating himself and others in the art of collecting fine antiques and art objects. Simpson Galleries' commitment to excellence and accur...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

| $200,000 | $25,000 |

About Auction

Sep 20, 2020

Including a rare document collection; clocks and timepieces; works by Porfirio Salinas, Frederic Remington, Édouard Cortès, Dorothy Hood, François Gall, Charles Russell, Peter Hurd, Henriette Wyeth, Mitchell Johnson, Gary Niblett and Frank Tenney Johnson; and French, English and American furniture. Simpson Galleries online_auctions@simpsongalleries.com

- Lot Description

A LATE MEXICAN-AMERICAN WAR ERA MAP, "Mapa de los Estados Unidos de Mejico, Revised Edition," JOHN DISTURNELL, NEW YORK,1848-1850, hand colored copper plate engraving on paper, the Gulf of Mexico with four inset maps, "Map Showing the Battlegrounds of (Palo Alto) the 8th and 9th, May 1846, by J.H. Eaton," "Plan of Monterrey and its Environs," "Chart of the Bay of Veracruz," and "Tampico and its Environs," at far right, "Diagram of the Battleground (of Buena Vista) February 22nd and 23rd 1847," in the lower left, "Table de Distancias.," "Tabla Estadistica.," and "Carta de los Caminos & Desde Vera Cruz Y Alvarado a Méjico," accompanied by two profiles of the routes "...between Mexico and Veracruz," and "...between Mexico and Acapulco," the upper right with engraving of Mexican eagle with snake in its beak, perched on cactus with names of Mexican states lettered on pads, above a bow and arrow; the hand coloring ordered as follows: Green-Spanish Boundary 1786, Blue-Boundary Proposed by Mexican Commissioners, Yellow-Boundary Claimed by the United States," with quotation, "Prior to the Revolution Texas and Coahuila were united to form one of the Federal States of the Mexican Republic," Red- Route of Gen. Taylor in south Texas and north Mexico, and Gen. Kearny's Route in the north tracking his "March of the 1st Dragoons" from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, Pink-Boundary Proposed by Mr. Trist U.S. Commissioner, presented with a gilt embossed green cloth cover board, "Map of the Republic of Mexico, Published by J. Disturnell, New York." 30" x 42" Note: The particular map noted for numerous editions with notable mistakes; this map is a rare example of a map that both has gross inaccuracies and served as an important tool for the United States and Mexican governments during land disputes and negotiations at the end of the Mexican American War. The present map includes detailed hand-drawn routes and boundaries that formed the face of the modern American landscape.The red route indicated in the Southern Texas/Northern Mexico area tracks future President Zachary Taylor's military expeditions during the Mexican-American War. "In the summer of 1845, Taylor, now sixty years old and stationed again at Fort Jesup, was ordered by the Polk administration to defend the recently annexed Texas republic. Commanding what would now be called the "Army of Occupation," Taylor moved his troops to Corpus Christi, at the mouth of the Nueces River, where he awaited reinforcements. By March 1846, with an army that now numbered 4,000, he moved further south, to the Rio Grande. When Mexican troops attacked U.S. forces in late April, President James K. Polk used the attack to ask Congress for a declaration of war. On May 18, though heavily outnumbered, Taylor defeated Mexican forces at Palo Alto; the following day he engaged the Mexican army again at Resaca de la Palma, driving it back to Matamoros. With the United States and Mexico now at war, Taylor established a base of operations at Camargo, on the Rio Grande, while he awaited reinforcements from the War Department, which had issued a call for volunteers. In September 1846, his army now numbering 6,500, Taylor marched south to lay siege to Monterey, Mexico's largest northern city, which was garrisoned by the 5,000-man Army of the North, commanded by General Pedro Ampudia. After three days of fighting, Taylor took the city, signing an eight-week armistice with Ampudia, who was allowed to withdraw. The news of the victory was offset in Washington by President Polk's belief that Taylor had missed an opportunity to end the war by allowing Ampudia to evacuate the city. The War Department ordered Taylor to terminate the armistice immediately, and pointedly refrained from congratulating the general on his victory. This brought an immediate chill to relations between Taylor and the Polk administration, which was undoubtedly aggravated by reports that the general was being courted by the Whig Party as a possible candidate for the presidency in 1848. The rift between Polk and Taylor became even wider when Washington decided at year's end to open up a new theater of operations in the south, under the command of Winfield Scott. Ordered to assume a defensive position and place a large portion of his army under Scott's command in anticipation of an amphibious landing at Vera Cruz, Taylor refused to be relegated to a secondary role. In defiance of orders from both Scott and the War Department, Taylor pushed south, encountering the Mexican army at Buena Vista, below Saltillo. Taylor's army repulsed several Mexican assaults on February 22 and 23. Although both sides claimed victory, the battle ended in a stalemate. Nonetheless, Taylor's Army of Occupation remained firmly in control of northern Mexico, and the battle was hailed as a great victory by the American press. The Battle of Buena Vista added further luster to Taylor's political fortunes. Known as 'Old Rough and Ready' for his simple manner and modest appearance, Taylor was now the most celebrated hero of the war. Still bristling at his treatment by the Polk administration, Taylor agreed to accept the nomination of the Whig party, despite the fact that he had not been active in politics, nor did he appear to hold particularly strong political convictions. Indeed, Taylor did not share many of the core Whig beliefs, such as support for a protective tariff, the national bank, and internal improvements. Nonetheless, the war hero easily defeated the Democratic candidate, Lewis Cass, whose support in the North was undercut by the Free Soil party, headed by long-time Democratic standard-bearer Martin Van Buren." - an excerpt from UT Arlington Library's Special Collections, A Continent Divided: The U.S. Mexico War, and with special thanks. The route of General Stephen W. Kearny in the north indicated, also in red in the north, established for the first time the United State's military control of the lands spanning from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas westward to Los Angeles. "The start of the U.S.-Mexico War found Kearny at Fort Leavenworth, where in May 1846 he gathered troops charged with conquering New Mexico and California. Kearny's forces left Fort Leavenworth in June 1846. Numbering 1,558 men, the "Army of the West" consisted of a battalion of Missouri Volunteers, two companies of regular infantry, five squadrons of the First Dragoons, Doniphan's Regiment of Missouri Mounted Volunteers, an interpreter, about fifty Indian guides, and a small body of Army Topographical Engineers. On July 22, the army reached Bent's Fort. Soon afterward, Kearny sent word to New Mexico Governor Manuel Armijo that the Americans intended to take possession of New Mexico. On August 15 the Americans entered Las Vegas, New Mexico, and three days later entered Santa Fe without opposition, Armijo having fled. Promising to respect New Mexican property and religion, Kearny established a legal code for New Mexico and installed Charles Bent, an American trader, as territorial governor. Kearny now received new orders from Washington, promoting him to the rank of brigadier general and instructing him to aid in the conquest of California...As Kearny headed west, resistance to U.S. rule flared in California. As his small force approached San Diego, where it planned to link up with Commodore Robert F. Stockton's marines, Kearny's weary dragoons encountered a force of 150 Californios. At the Battle of San Pascual on December 6, Kearny was seriously wounded and 18 of his men killed. The force was rescued the following day by the timely arrival of a relief column led by Stockton. While the dragoons rested, Stockton prepared to retake Los Angeles. In late December he and Kearny led a joint Army-Navy force of about 600 men out of San Diego. Defeating Mexican and California troops at the battles of Rio San Gabriel and La Mesa, Stockton and Kearny's troops entered Los Angeles. Signing the Treaty of Cahuenga, which ended Californian resistance to U.S. occupation, Stockton turned over military command to Kearny and appointed John C. Fremont governor."- an excerpt from UT Arlington Library's Special Collections, A Continent Divided: The U.S. Mexico War, and with special thanks. Layering each territory boundary by color gives the viewer an instant look at the intense negotiations that took place between Nicholas Trist in pink and the Mexican government in blue. The University of Texas at Arlington writes, "Nicholas P. Trist, the American diplomat who negotiated the treaty that ended the U.S.-Mexico War...Just as he was beginning to enter into negotiations with the provisional Mexican government that had been hastily organized at the town of Querétaro under a new President, Manuel Peña y Peña, Trist received word from Secretary of State James Buchanan that he (Trist) had been recalled by an impatient President Polk. Buchanan's dispatch stated further that if the Mexicans wanted peace, they would have to send an emissary to the United States. Realizing that to abandon his work and leave Mexico at that crucial juncture would almost certainly have negative consequences for both countries, Trist decided to ignore the recall, which General Scott and all three Mexican negotiators, Luis G. Cuevas, Bernardo Couto, and Miguel Atristain, encouraged him to do. On February 2, 1848, Trist signed the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo on behalf of the United States while Cuevas, Couto, and Atristain signed for Mexico. The treaty's most far-reaching provisions included recognition by Mexico of the Rio Grande as the boundary of Texas, the United States government's assumption of $3 million Mexico owed to private U.S. citizens, and Mexico's agreement to sell Upper California and New Mexico, a vast expanse that makes up the present-day states of California, Arizona, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico, and part of Colorado, for $15 million. When the treaty reached Washington, Polk was outraged that Trist, who technically had no authority to make an agreement with Mexico on account of his recall, had ignored the President's order. At first, Polk considered discarding the agreement but realizing that all his principal war goals had been accomplished and that the country was in no mood to prolong the conflict, he sent it to the Senate, which ratified the treaty on March 10, 1848. Both houses of the Mexican Congress ratified it on May 19." -an excerpt from UT Arlington Library's Special Collections, A Continent Divided: The U.S. Mexico War, and with special thanks.Attributed as an eighth edition or later, with special consideration to the appearance of the inset maps in the Gulf of Mexico. This revision containing the inset maps in the Gulf coinciding with the Presidential term of Zachary Taylor and the end of the Mexican-American War. The inset maps celebrate Zachary Taylor's many military achievements. The present map with special hand coloring notes the fundamentally transformative time for the United States at the end of the Mexican-American War, which effectively established the United States of America from coast to coast, fulfilling Manifest Destiny. No longer would the United States boundary ever change or waver as much as this map with hand color indicates it once did. An invaluable and education addition to any American map collection.Some stains, losses, creases, joined neat line, tears at edges, float mounted with repairs and indrawing, waving, Simpson Galleries strongly encourages in-person inspection of items by the bidder. Statements by Simpson Galleries regarding the condition of objects are for guidance only and should not be relied upon as statements of fact and do not constitute a representation, warranty, or assumption of liability by Simpson Galleries. All lots offered are sold "AS IS." NO REFUNDS will be issued based on condition.

Condition

- Shipping Info

-

**SIMPSON GALLERIES, LLC. DOES NOT PROVIDE SHIPPING SERVICES OR SHIPPING QUOTES.** Shipping may be secured through - The UPS Store: auctions@epicpartnershipco.com 281-764-9551, The UPS Store: store1733@theupsstore.com 713-942-7775, PACK-N-SEND: sales@pack-n-send.com 713-266-1450, ACTS Crating and Transportation Services: crating@actsintl.com 713-869-2269, NAVIS Pack & Ship: 17013tx@gonavis.com 713-352-3038, A Better Mover Inc: travis@abettermoverinc.com or abettermover@yahoo.com 404-754-0111, or the shipper of your choice. We are open for shipper pick-up Tuesday - Thursdays from 10 am to 3 pm or by appointment.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB