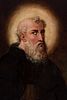

Spanish school; Last third of the 16th century. "San Antón". Oil on panel. Hemmed.

Lot 64

About Seller

Setdart Auction House

Carrer Aragó 346

Barcelona

Spain

Setdart Subastas was born in 2004 and is currently the first online art auction in Spain with solidity, prestige and reliability guaranteed by our more than 60,000 users. Setdart has a young, dynamic and enterprising team ready to successfully manage the purchase and sale of art works through custom...Read more

Estimate:

EUR€7,000 - EUR€9,000

$7,526.88 - $9,677.42

Absentee vs Live bid

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| EUR€0 | EUR€10 |

| EUR€200 | EUR€25 |

| EUR€500 | EUR€50 |

| EUR€1,000 | EUR€100 |

| EUR€3,000 | EUR€200 |

| EUR€5,000 | EUR€500 |

| EUR€10,000 | EUR€1,000 |

| EUR€20,000 | EUR€2,000 |

| EUR€50,000 | EUR€5,000 |

About Auction

By Setdart Auction House

Jun 30, 2021

Set Reminder

2021-06-30 08:30:00

2021-06-30 08:30:00

America/New_York

Bidsquare

Bidsquare : Old Masters

https://www.bidsquare.com/auctions/setdart-auction-house/old-masters-7134

Setdart Auction House sofia@setdart.com

Setdart Auction House sofia@setdart.com

- Lot Description

Spanish school; Last third of the 16th century. "San Antón". Oil on panel. Hemmed. Presents repaints and losses in the upper areas. Measures: 128 x 57 cm. According to legend, St. Anthony Abbot was born in Egypt in 251, and at a very young age he retired to the solitude of the desert. Towards the end of his life, he visited Paul the hermit, superior of the anchorites of the Thebaid, miraculously fed by a raven that day carried in its beak double ration of bread. Some time later, upon learning of the death of his venerable brother, he went to bury him with the help of two lions. In addition, in Catalonia, adventures and miracles were attributed to him, which served as a theme for Jaume Huguet for his altarpiece of Saint Anthony in Barcelona. The order of the Antonines was founded in the 11th century under the invocation of Saint Anthony as a holy healer. To maintain their encomiendas and hospitals, the Antonines dedicated themselves to raising pigs. They enjoyed the privilege of letting their animals, recognizable by the bell that jingled on their necks, roam the streets of the villages and the communal lands. Hence one of the most popular attributes of the saint is an animal with a cowbell around its neck, usually a pig. The extraordinary popularity of Saint Anthony is due, however, to his fame as a healer saint, and that is why he is represented here with a crutch as an iconographic attribute. Usually, this saint is represented as a bearded old man wearing a hooded sackcloth, a common garment of the Antonines. Apart from those already mentioned, another of his most frequent attributes is the tau. Spain is, at the beginning of the 16th century, the European nation best prepared to receive the new humanist concepts of life and art due to its spiritual, political and economic conditions, although from the point of view of plastic forms, its adaptation of those introduced by Italy was slower due to the need to learn the new techniques and to change the taste of the clientele. Sculpture reflects perhaps better than other artistic fields this eagerness to return to the classical Greco-Roman world that exalts in its nudes the individuality of man, creating a new style whose vitality surpasses the mere copy. Soon the anatomy, the movement of the figures, the compositions with a sense of perspective and balance, the naturalistic play of the folds, the classical attitudes of the figures began to be valued; but the strong Gothic tradition maintains the expressiveness as a vehicle of the deep spiritualistic sense that informs our best Renaissance sculptures. This strong and healthy tradition favors the continuity of religious painting that accepts the formal beauty offered by Italian Renaissance art with a sense of balance that avoids its predominance over the immaterial content that animates the forms. In the first years of the century, Italian works arrived to our lands and some of our artists went to Italy, where they learned first hand the new norms in the most progressive centers of Italian art, such as Florence or Rome, and even in Naples.

- Shipping Info

-

In-house shipping available. Please inquire at admin@setdart.com.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB