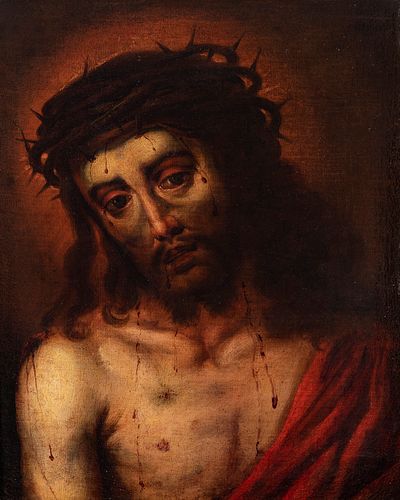

Sevillian school; second half of the seventeenth century. "Ecce Homo". Oil on canvas. Relined.

Lot 63

About Seller

Setdart Auction House

Carrer Aragó 346

Barcelona

Spain

Setdart Subastas was born in 2004 and is currently the first online art auction in Spain with solidity, prestige and reliability guaranteed by our more than 60,000 users. Setdart has a young, dynamic and enterprising team ready to successfully manage the purchase and sale of art works through custom...Read more

Estimate:

EUR€2,500 - EUR€3,000

$2,688.17 - $3,225.81

Absentee vs Live bid

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| EUR€0 | EUR€10 |

| EUR€200 | EUR€25 |

| EUR€500 | EUR€50 |

| EUR€1,000 | EUR€100 |

| EUR€3,000 | EUR€200 |

| EUR€5,000 | EUR€500 |

| EUR€10,000 | EUR€1,000 |

| EUR€20,000 | EUR€2,000 |

| EUR€50,000 | EUR€5,000 |

About Auction

By Setdart Auction House

Nov 3, 2021

Set Reminder

2021-11-03 08:00:00

2021-11-03 08:00:00

America/New_York

Bidsquare

Bidsquare : OLD MASTERS

https://www.bidsquare.com/auctions/setdart-auction-house/old-masters-7786

Setdart Auction House sofia@setdart.com

Setdart Auction House sofia@setdart.com

- Lot Description

Sevillian school; second half of the seventeenth century. "Ecce Homo". Oil on canvas. Relined. Measurements: 53 x 40 cm; 72 x 59 cm (frame). In this devotional canvas, painted for an altar or private chapel, the theme of Ecce Homo is represented, very common in this type of paintings. Of simple and clear composition, with the face of Christ in the foreground, the absence of narrative details deepens the expressive power and pathos, designed to move the soul of the faithful who pray before the image, within a tremendist sense very typical of the baroque in Catholic countries. The theme of Ecce Homo belongs to the cycle of the Passion, and precedes the episode of the Crucifixion. Following this iconography, Jesus is presented at the moment when the soldiers mock him, after crowning him with thorns, dressing him in a purple tunic (here red, symbolic color of the Passion) and placing a reed in his hand, kneeling and exclaiming "Hail, King of the Jews!". The words "Ecce Homo" are those pronounced by Pilate when presenting Christ before the crowd; their translation is "behold the man", a phrase by which he mocks Jesus and implies that Christ's power was not such in front of that of the leaders who were judging him there. Formally this work is dominated by the light treatment, very contrasted and dramatic, based on a spotlight that falls directly on the figure of Christ. The dramatism that stands out in the scene reflected in the blood of the body that falls on the body of Christ, contrasts with the austere attitude and of recollection that denotes the posture of the body. It is this body composition that brings the artist closer to the work of Murillo. Considered by some as the painter who best defines the Spanish Baroque, Bartolomé Esteban Murillo exerted a remarkable influence among his Sevillian contemporaries and, after his death, his wake can be found in other schools even to this day, especially in religious art. In the 18th century his language and iconographic formulas were widely followed and repeated, and during Romanticism numerous copies of his works were made. However, it will be in the Baroque of the eighteenth century when the importance of his influence is most appreciated, spread by his numerous disciples and followers. In fact, in that century he was the best known and most appreciated Spanish painter outside Spain, the only one of whom Sandrart includes a biography in his "Academia picturae eruditae", a work of the late seventeenth century. In the last decades of the 17th century, the emotional, sweet and delicate sentimentality of Murillo prevailed in Seville over the more dramatic one of Valdés Leal, and hence the predominance of his influence in the following century. However, as time progresses, we will find ourselves before an increasingly superficial influence, which focuses on the imitation of models and compositions, but leaving aside his plastic language, in favor of formulas more typical of the new century.

- Shipping Info

-

In-house shipping available. Please inquire at admin@setdart.com.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB