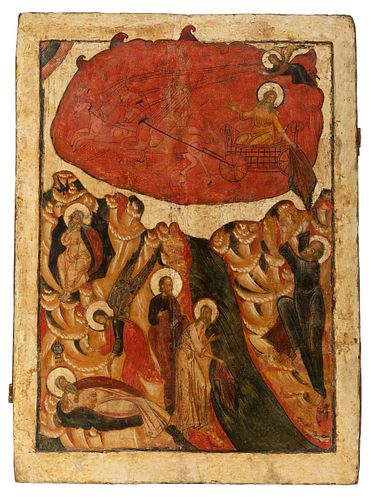

Russian school, 15th-16th c. 15TH-16TH C. "Ascension of Elijah". Tempera on panel.

Lot 13

About Seller

Setdart Auction House

Carrer Aragó 346

Barcelona

Spain

Setdart Subastas was born in 2004 and is currently the first online art auction in Spain with solidity, prestige and reliability guaranteed by our more than 60,000 users. Setdart has a young, dynamic and enterprising team ready to successfully manage the purchase and sale of art works through custom...Read more

Estimate:

EUR€15,000 - EUR€18,000

$15,625 - $18,750

Absentee vs Live bid

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| EUR€0 | EUR€10 |

| EUR€200 | EUR€25 |

| EUR€500 | EUR€50 |

| EUR€1,000 | EUR€100 |

| EUR€3,000 | EUR€200 |

| EUR€5,000 | EUR€500 |

| EUR€10,000 | EUR€1,000 |

| EUR€20,000 | EUR€2,000 |

| EUR€50,000 | EUR€5,000 |

About Auction

By Setdart Auction House

Sep 23, 2021

Set Reminder

2021-09-23 10:00:00

2021-09-23 10:00:00

America/New_York

Bidsquare

Bidsquare : RUSSIAN ICONS

https://www.bidsquare.com/auctions/setdart-auction-house/russian-icons-7431

Setdart Auction House sofia@setdart.com

Setdart Auction House sofia@setdart.com

- Lot Description

Russian school, 15th-16th c. 15TH-16TH C. "Ascension of Elijah". Tempera on panel. Measurements: 115 x 85 cm. Elijah was one of the most venerated Old Testament saints in Old Rus, even before the Christianisation of Rus in 988. Today he is considered the protector of the air forces. He is one of the few prophets equally esteemed in Islam, Judaism and Christianity. There is very little information about his origin and his name, which probably comes from Hebrew and means "my God is Yahweh (the one God)", is not known exactly. During his lifetime, Elijah openly criticised the pagan king of Israel, Ahab, and his wife Jezebel. Because of their lack of faith in Christianity, God punished Israel with a drought, which lasted three years. During this period, Elijah lived in the desert by a small river, or a natural water source, and was fed with the help of the ravens that brought him food. When the people of Israel finally had enough, Elijah offered him a test by building two altars, one pagan and one Christian. The one on which the fire would fall that night would be the religion he would follow. God lit the Christian altar, putting an end to paganism in Israel. As a gift for this rigorous faith and virtue, Elijah was ascended to heaven. It is precisely this episode that is depicted in the central scene of our icon. This icon is a clear example of that exceptional period of full development of the Russian pictorial identity understood between the 15th and the beginning of the 17th century. By the 15th century, due to the fall of the Byzantine Empire, Russian icon painters, a priori followers of Byzantine traditions, began to chart their own independent artistic path, reflected both in style and in the use of materials. This effervescent period was further boosted by the presence on the territory of Old Rus' territory of virtuoso painters such as Feofan the Greek and his pupil Andrey Rubliov, who worked mainly in Moscow. This lot, dedicated to the Ascension of Elijah to Heaven, and probably executed in the north of Russia around the 16th century, is a clear example of this search for a new language. The first thing that indicates this is its physical qualities, such as its significant size. In medieval Russia, full of forests, it was very common to paint large icons, up to three metres high, to decorate churches. Secondly, the pictorial style of the icon speaks for itself. The image is divided into two registers. It recounts the life of the prophet Elijah in the form of simultaneous scenes, instead of the hagiographic cells typical of Russian icons. The composition should be viewed from the scene at the centre left, where we see the prophet receiving a loaf of bread from the raven's beak. This is followed by the scene with the angel, who descended from heaven to deliver the message to Elijah as he slept. In the third miniature we see the miraculous passage, when Elijah parted the river Jordan, touching its surface with his clothes. Finally, the story culminates with the ascension of Elijah, still mortal, in the chariot with horses, as the gift for his rigorous faith and virtue. This icon is surprising for its dynamism, as the two horizontal registers are linked on the far right by Elijah's arms, creating a truly circular composition that does not let the viewer's eye escape. In turn, the upper register, in which we find the hand of God, and Elijah's miraculous cloud, whose irregular shape crosses the frame of the icon, adds a special compositional dynamism. All these characteristics indicate that this is a true masterpiece.

- Shipping Info

-

In-house shipping available. Please inquire at admin@setdart.com.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB