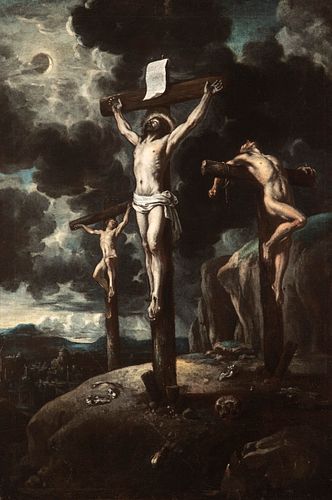

Madrid School; second half of the seventeenth century. "Calvary". Oil on canvas. Relined. Frame from a later period, 19th century.

Lot 65

About Seller

Setdart Auction House

Carrer Aragó 346

Barcelona

Spain

Setdart Subastas was born in 2004 and is currently the first online art auction in Spain with solidity, prestige and reliability guaranteed by our more than 60,000 users. Setdart has a young, dynamic and enterprising team ready to successfully manage the purchase and sale of art works through custom...Read more

Estimate:

EUR€16,000 - EUR€20,000

$17,204.30 - $21,505.38

Absentee vs Live bid

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| EUR€0 | EUR€10 |

| EUR€200 | EUR€25 |

| EUR€500 | EUR€50 |

| EUR€1,000 | EUR€100 |

| EUR€3,000 | EUR€200 |

| EUR€5,000 | EUR€500 |

| EUR€10,000 | EUR€1,000 |

| EUR€20,000 | EUR€2,000 |

| EUR€50,000 | EUR€5,000 |

About Auction

By Setdart Auction House

May 31, 2021

Set Reminder

2021-05-31 08:30:00

2021-05-31 08:30:00

America/New_York

Bidsquare

Bidsquare : OLD MASTERS - Day 1

https://www.bidsquare.com/auctions/setdart-auction-house/old-masters---day-1-6998

Setdart Auction House sofia@setdart.com

Setdart Auction House sofia@setdart.com

- Lot Description

Madrid School; second half of the seventeenth century. "Calvary". Oil on canvas. Relined. Frame from a later period, 19th century. Measures: 88.5 x 60 cm; 108 x 80 cm (frame). This canvas shows the Crucifixion from a low point of view that brings a greater roundness to the dimensions of the figures. It is a work that shows the scene of the Crucified Christ together with Dimas and Gestas, the good thief and the bad thief. This scene is narrated in the Gospel of Luke (Lk. 23, 32-33). "They also brought two other malefactors to be put to death with him. When they came to the place called Calvary, there they crucified him and the malefactors, one on the right and the other on the left." The scene stands out for its crudeness, not only because of the chosen theme, but also because of the dark palette, with strong contrasts of light and metallic tones. The bodies stand out against the dark background, by their whitish color, and in turn by the distortion of the anatomical dimensions, which in this case are elongated, with respect to the classical canon. The scene is completed by an abrupt and solitary landscape, where bone remains can be seen on the ground. The scene that stands out for its expressiveness differs somewhat from the traditional form of representation of Calvary based on Byzantine Déesis, which represented Christ in Majesty accompanied by Mary and St. John the Baptist. In Western art, the representation of Christ on the cross was preferred, as a narrative scene, and the figure of St. John the Baptist was replaced by that of John the Evangelist. An image that in its conception and form is the result of the expression of the people and the deepest feelings that nestled in it. With the economy of the State broken, the nobility in decline and the high clergy burdened with heavy taxes, it was the monasteries, the parishes and the confraternities of clerics and laymen who promoted its development, the works sometimes being financed by popular subscription. Painting was thus forced to capture the prevailing ideals in these environments, which were none other than religious ones, at a time when the Counter-Reformation doctrine demanded from art a realistic language so that the faithful would understand and identify with what was represented, and an expression endowed with an intense emotional content to increase the fervor and devotion of the people. The religious subject is, therefore, the preferred theme of the Spanish sculpture of this period, which starts in the first decades of the century with a priority interest in capturing the natural, to progressively intensify throughout the century the expression of expressive values, which is achieved through the movement and variety of gestures, the use of light resources and the representation of moods and feelings. The Madrid school arose around the court of Philip IV first and Charles II later, and developed throughout the seventeenth century. Analysts of this school have insisted on considering its development as a result of the agglutinating power of the court; what is truly decisive is not the place of birth of the different artists, but the fact that they were educated and worked around and for a nobiliary and religious clientele located next to the royalty. This allows and favors a stylistic unity, although the logical divergences due to the personality of the members can be appreciated. In its origin, the Madrid school is linked to the rise to the throne of Philip IV, a monarch who made Madrid, for the first time, an artistic center. This meant an awakening of the nationalist conscience by allowing a liberation from the previous Italianizing molds to jump from the last echoes of Mannerism to Tenebrism. This will be the first step of the school, which in a gradual sense will walk successively until the attainment of a more autochthonous baroque language and linked to the political, religious and cultural conceptions of the monarchy.

- Shipping Info

-

In-house shipping available. Please inquire at admin@setdart.com.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB