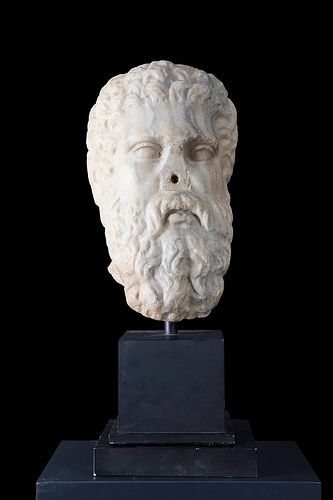

Head of a philosopher. Imperial Rome, 1st century A.D. Marble. Provenance: Former collection J. Castro, 1930. Measures: 32 x 20 cm.

Lot 66

About Seller

Setdart Auction House

Carrer Aragó 346

Barcelona

Spain

Setdart Subastas was born in 2004 and is currently the first online art auction in Spain with solidity, prestige and reliability guaranteed by our more than 60,000 users. Setdart has a young, dynamic and enterprising team ready to successfully manage the purchase and sale of art works through custom...Read more

Estimate:

EUR€30,000 - EUR€35,000

$31,914.89 - $37,234.04

Absentee vs Live bid

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| EUR€0 | EUR€10 |

| EUR€200 | EUR€25 |

| EUR€500 | EUR€50 |

| EUR€1,000 | EUR€100 |

| EUR€3,000 | EUR€200 |

| EUR€5,000 | EUR€500 |

| EUR€10,000 | EUR€1,000 |

| EUR€20,000 | EUR€2,000 |

| EUR€50,000 | EUR€5,000 |

About Auction

By Setdart Auction House

Dec 22, 2021

Set Reminder

2021-12-22 08:30:00

2021-12-22 08:30:00

America/New_York

Bidsquare

Bidsquare : Archaeology, Session I

https://www.bidsquare.com/auctions/setdart-auction-house/archaeology-session-i-8050

Setdart Auction House sofia@setdart.com

Setdart Auction House sofia@setdart.com

- Lot Description

Head of a philosopher. Imperial Rome, 1st century A.D. Marble. Provenance: Former collection J. Castro, 1930. Measures: 32 x 20 cm. We are in front of the portrait of a philosopher of the Classical Antiquity. It is a piece worked with a naturalistic idealism of great delicacy and beauty. The veristic workmanship denotes a great technical skill and physiognomist sensitivity of the sculptor, who knows how to masterfully enhance the principles of order, clarity and balance that governed the Greco-Latin art. The sculptor imprints on the marble the right ductility to represent beard and hair, in the same way that he extracts precise plastic qualities to the flesh and describes a fully naturalistic facial orography, in the tanned expression of the man, in his sunken sockets and lively eyes. The Romans brought two important novelties to the world of sculpture: the portrait and the historical relief, neither of which existed in the Greek world. However, they followed the Greek models for much of their sculptural production, a base that in Rome would be combined with the Etruscan tradition. After the first contacts with the Greece of classicism through the colonies of Magna Graecia, the Romans conquered Syracuse in 212 BC, a rich and important Greek colony located in Sicily, adorned with a large number of Hellenistic works. The city was sacked and its artistic treasures taken to Rome, where the new style of these works soon replaced the Etruscan-Roman tradition that had prevailed until then. Cato himself denounced the sacking and decoration of Rome with Hellenistic works, which he considered a dangerous influence on native culture, and deplored the Romans' applauding of statues from Corinth and Athens, while ridiculing the decorative terracotta tradition of ancient Roman temples. However, these oppositional reactions were in vain; Greek art had subdued Etruscan-Roman art in general, to the point that Greek statues were among the most coveted prizes of war, being displayed during the triumphal procession of the conquering generals. Shortly thereafter, in 133 BC, the Empire inherited the kingdom of Pergamon, where there was an original and thriving school of Hellenistic sculpture. The huge Pergamon Altar, the "Gallus committing suicide" or the dramatic group "Laocoön and his sons" were three of the key creations of this Hellenistic school. On the other hand, after Greece was conquered in 146 B.C. most Greek artists settled in Rome, and many of them devoted themselves to making copies of Greek sculptures, very fashionable at that time in the capital of the Empire. Thus, numerous copies of Praxiteles, Lysippus and classical works of the 5th century B.C. were produced, giving rise to the Neo-Attic school of Rome, the first neoclassical movement in the History of Art. However, between the end of the 2nd century BC and the beginning of the 1st century BC there was a change in this purist Greek trend, which culminated in the creation of a national school of sculpture in Rome, from which emerged works such as the Altar of Aenobarbus, which already introduced a typically Roman narrative concept, which would become a chronicle of daily life and, at the same time, of the success of its political model. This school will be the precursor of the great imperial art of Augustus, in whose mandate Rome became the most influential city of the Empire and also the new center of Hellenistic culture, as Pergamon and Alexandria had been before, attracting a large number of Greek artists and craftsmen. In the Augustan era Rome contributed to the continuity and renewal of a tradition that had already enjoyed centuries of prestige, and which had dictated the character of all the art of the area. In this new stage, Greek aesthetics and technique will be applied to the themes of this new Rome.

- Shipping Info

-

In-house shipping available. Please inquire at admin@setdart.com.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB