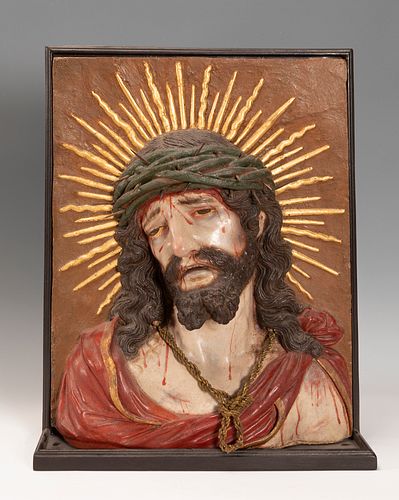

Granada school of the second half of the seventeenth century. Attributed to the García Brothers: MIGUEL FRANCISCO GARCÍA AND JERÓNIMO FRANCISCO GARCÍA

Lot 64

About Seller

Setdart Auction House

Carrer Aragó 346

Barcelona

Spain

Setdart Subastas was born in 2004 and is currently the first online art auction in Spain with solidity, prestige and reliability guaranteed by our more than 60,000 users. Setdart has a young, dynamic and enterprising team ready to successfully manage the purchase and sale of art works through custom...Read more

Estimate:

EUR€7,000 - EUR€9,000

$7,526.88 - $9,677.42

Absentee vs Live bid

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| EUR€0 | EUR€10 |

| EUR€200 | EUR€25 |

| EUR€500 | EUR€50 |

| EUR€1,000 | EUR€100 |

| EUR€3,000 | EUR€200 |

| EUR€5,000 | EUR€500 |

| EUR€10,000 | EUR€1,000 |

| EUR€20,000 | EUR€2,000 |

| EUR€50,000 | EUR€5,000 |

About Auction

By Setdart Auction House

Oct 20, 2021

Set Reminder

2021-10-20 07:30:00

2021-10-20 07:30:00

America/New_York

Bidsquare

Bidsquare : OLD MASTERS

https://www.bidsquare.com/auctions/setdart-auction-house/old-masters-7700

Setdart Auction House sofia@setdart.com

Setdart Auction House sofia@setdart.com

- Lot Description

Granada school of the second half of the seventeenth century. Attributed to the García Brothers: MIGUEL FRANCISCO GARCÍA AND JERÓNIMO FRANCISCO GARCÍA (Granada, XVI and XVII centuries). "Ecce Homo. Polychrome and gilded plaster. Size: 48 x 38 x 10 cm; 52 x 40 x 11 cm. Active in Granada during the second half of the 17th century, the García brothers specialized in the production of clay pieces. The sculpture in question, possibly belonging to a very small series, has been made in gilded and polychrome plaster, a technical rarity that increases, even more if possible, the interest of this specimen. It deals with the theme of the Ecce Homo, worked with a language attentive to detail, of great pathos. Special importance is given to the crown of thorns as the supreme symbol of Christ's suffering, accompanied by the facial expression full of suffering and the blood spilled on his complexion and body. The present work should be compared, due to its formal and technical characteristics, with the Christ of the Gospel Chapel in the Church of San Justo y Pastor in Granada. The brothers Miguel and Jerónimo Francisco García, canons of the Colegiata del Salvador in Granada, were two sculptors active between the 16th and 17th centuries, who can be placed in the transition phase from naturalism to early baroque. They worked in clay and wood, and are known for a set of Ecce Homos usually of small size, meticulous modeling and great expressiveness. Recently, a group of terracotta reliefs representing different saints in penitence has been added to their catalog of works: St. John the Baptist, St. Jerome, etc. They have been attributed the crucifix of the sacristy of the Cathedral of Granada, traditionally considered the work of Montañés. Both brothers were responsible for the creation of new iconographic models that helped to consolidate the incipient taste for naturalism in the Granada school. It is true that there were many who inspired him when carrying out his work, but we can say without fear of being wrong, that his works served as a reference to other great artists such as Alonso de Mena. Men of their time, and aware of the peculiarities of working with clay in the right way. They are the founders of the school of barrists of Granada, and it is from their production that clay, that ignoble material, begins to acquire new nuances. Relegated its use in previous times to the realization of domestic furnishings, they would be responsible for raising it to the highest spheres. Following in their footsteps, Alonso Cano, Diego and José de Mora, José Risueño, among many others, would establish this tradition, whose peak would be reached in the 19th century by the baristas of the time: Manuel González, Miguel Marín, Antonio Jiménez Rada and, of course, Francisco Morales González, among many others.

- Shipping Info

-

In-house shipping available. Please inquire at admin@setdart.com.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB