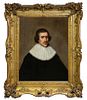

Dutch school of the first half of the seventeenth century. "Portrait of a man with a ruff", 1635. Oil on panel.

Lot 83

About Seller

Setdart Auction House

Carrer Aragó 346

Barcelona

Spain

Setdart Subastas was born in 2004 and is currently the first online art auction in Spain with solidity, prestige and reliability guaranteed by our more than 60,000 users. Setdart has a young, dynamic and enterprising team ready to successfully manage the purchase and sale of art works through custom...Read more

Estimate:

EUR€12,000 - EUR€15,000

$12,903.23 - $16,129.03

Absentee vs Live bid

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| EUR€0 | EUR€10 |

| EUR€200 | EUR€25 |

| EUR€500 | EUR€50 |

| EUR€1,000 | EUR€100 |

| EUR€3,000 | EUR€200 |

| EUR€5,000 | EUR€500 |

| EUR€10,000 | EUR€1,000 |

| EUR€20,000 | EUR€2,000 |

| EUR€50,000 | EUR€5,000 |

About Auction

By Setdart Auction House

Oct 20, 2021

Set Reminder

2021-10-20 07:30:00

2021-10-20 07:30:00

America/New_York

Bidsquare

Bidsquare : OLD MASTERS

https://www.bidsquare.com/auctions/setdart-auction-house/old-masters-7700

Setdart Auction House sofia@setdart.com

Setdart Auction House sofia@setdart.com

- Lot Description

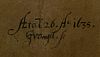

Dutch school of the first half of the seventeenth century. "Portrait of a man with a ruff", 1635. Oil on panel. With label of the Board of Seizure and Protection of Artistic Heritage. With date and inscription on the upper right side. Measurements: 75 x 60 cm; 105 x 87 cm (frame). Resolved with the meticulous technique that characterized the paintings of the Dutch school, the portrait that occupies us captures with precision the physiognomy and the character of the personage, without idealisms. The painter extracts the right qualities of the fabrics, the brightness of the doublet and the delicacy of the ruff. According to the inscription on its upper right side, the work was painted by the painter "Granjel" at the age of 26. Undoubtedly, it was in the painting of the Dutch school that the consequences of the political emancipation of the region, as well as the economic prosperity of the liberal bourgeoisie, were most openly manifested. The combination of the discovery of nature, objective observation, the study of the concrete, the appreciation of the everyday, the taste for the real and material, the sensitivity to the seemingly insignificant, made the Dutch artist commune with the reality of everyday life, without seeking any ideal alien to that same reality. The painter did not seek to transcend the present and the materiality of objective nature or to escape from tangible reality, but to envelop himself in it, to become intoxicated by it through the triumph of realism, a realism of pure illusory fiction, achieved thanks to a perfect and masterful technique and a conceptual subtlety in the lyrical treatment of light. Because of the break with Rome and the iconoclastic tendency of the Reformed Church, paintings with religious themes were eventually eliminated as a decorative complement with a devotional purpose, and mythological stories lost their heroic and sensual tone, in accordance with the new society. Thus, portraits, landscapes and animals, still life and genre painting were the thematic formulas that became valuable in their own right and, as objects of domestic furniture - hence the small size of the paintings - were acquired by individuals of almost all classes and social classes.

- Shipping Info

-

In-house shipping available. Please inquire at admin@setdart.com.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB