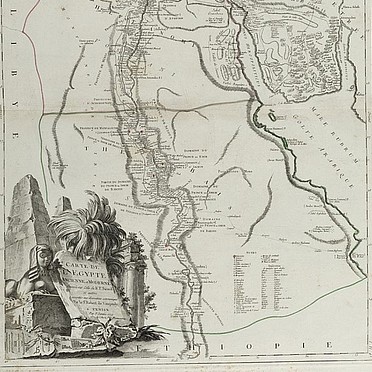

"CENTRAL PART OF THE STATES OF THE CHURCH", map from the "Atlas Universel, dressé sur les meilleures cartes modernes", second half of the 18th century

Lot 26

About Seller

Setdart Auction House

Carrer Aragó 346

Barcelona

Spain

Setdart Subastas was born in 2004 and is currently the first online art auction in Spain with solidity, prestige and reliability guaranteed by our more than 60,000 users. Setdart has a young, dynamic and enterprising team ready to successfully manage the purchase and sale of art works through custom...Read more

Estimate:

EUR€300 - EUR€400

$312.50 - $416.67

Absentee vs Live bid

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| EUR€0 | EUR€10 |

| EUR€200 | EUR€25 |

| EUR€500 | EUR€50 |

| EUR€1,000 | EUR€100 |

| EUR€3,000 | EUR€200 |

| EUR€5,000 | EUR€500 |

| EUR€10,000 | EUR€1,000 |

| EUR€20,000 | EUR€2,000 |

| EUR€50,000 | EUR€5,000 |

About Auction

By Setdart Auction House

Sep 30, 2021

Set Reminder

2021-09-30 07:30:00

2021-09-30 07:30:00

America/New_York

Bidsquare

Bidsquare : ANTIQUE CARTOGRAPHY AND ARCHITECTURE PRINTS

https://www.bidsquare.com/auctions/setdart-auction-house/antique-cartography-and-architecture-prints-7542

Setdart Auction House sofia@setdart.com

Setdart Auction House sofia@setdart.com

- Lot Description

"CENTRAL PART OF THE STATES OF THE CHURCH", map from the "Atlas Universel, dressé sur les meilleures cartes modernes", second half of the 18th century. Illuminated engraving (colour demarcations). Edition M. Remondini, Venice, 1784. Hand-numbered on the reverse (no. 21), corresponding to the numbering stipulated in the index. The lot is accompanied by a copy of the title page of the atlas. Measurements: 46 x 62 cm (print); 53 x 76 cm (paper). The map in question represents the territory corresponding to the Papal States, containing the legislations of Urbino, the Marche, Umbria, with the territories of Orvieto, Pérouse and Città del Castello. It is part of the set of three maps (coinciding with the southern part, the northern part and the middle part) which, in their entirety, form the cartographic documents of the State of the Church. The three maps derive from a major topographical survey carried out by Roger Boscovich (1711-1787), one of the most prominent Croatian scientists of the 18th century, whose varied scientific work included the creation of the first map of the Papal States, based on modern principles of geodetic topography. For the monumental work, Boscovich was assisted by the English Jesuit Father Christopher Maire. Both of them renewed the map of the State of the Church, up to that time with many errors, introducing the correct indication of the geographical position of the main towns of the State and studying the different geographical features known up to that time. Santini's map is a faithful copy of Boscovich's map. The origin of the "Atlas Universel, dressé sur les meilleures cartes modernes" (Universal Atlas made from the best modern maps) goes back to 1757, when Gilles Robert de Vaugondy (1668-1766) and his son Didier Robert de Vaugondy (1723-1786), geographers to the King of France, formed one of the most renowned workshops for the production and manufacture of maps and globes in France. The Vaugondys' excellent position in the field of topography, coupled with their family ties to Nicolas Sanson, one of the most important cartographers of the 17th century, led the Vaugondys to inherit much of the cartographic material that the latter had accumulated over the years, giving birth to the ambitious and unique Universal Atlas of which our map is a part. The copy became a commercial and cartographic success with enormous influence throughout Europe, which is why the brothers Paolo and Francesco Santini, Venetian engravers, did not miss the opportunity to acquire the original plates from the Vaugondy brothers. Thus, in 1776, the Santini brothers commissioned the production of new copperplates, while substantially maintaining the original design, keeping the place names and the inscriptions in French as defined in the 1757 copy. Due to their knowledge of the Italian territory, the Santini's changes mainly affected the maps of the Italian regions. The following year, Paolo Santini ceded all his publication rights to M. Remondini, who in 1777 and 1784 republished the same Atlas, but with his name. The copy of which our map is part, published in 1784, maintains the exceptionality of the original work of the Vaugondy family: the meticulous treatment of the information (based on the revision of the oldest maps available, buying them with the most updated material at the time); the incorporation of the latest academic research in force at that time; the integration of their own astronomical observations (correcting if necessary even latitude and longitude) or the great decorativism of each one of their maps. As in the vast majority of cartographic documents produced in France during the 18th century, the map in question is characterised by its enormous pictorial value and great attention to detail. Antique maps are one of the most complete documentary typologies. Their dual nature, cartographic and historical, attracts the attention of the most demanding collectors, who see in cartography a faithful reflection of the past, and are committed to their purchase and dissemination on the art market. The rarity of some of the editions, together with the longevity of many of the copies, make the possession and enjoyment of antique cartography an increasingly fashionable pleasure among art lovers. Understood as authentic reminiscences of the past, antique maps become a conscientious reflection of how the territory was divided in the past, or how geographical features define our world. Their decorative character, added to the meticulous and ambitious work of the cartographers, turn these pieces into authentic works of art.

- Shipping Info

-

In-house shipping available. Please inquire at admin@setdart.com.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB