GERTRUDE ABERCROMBIE (AMERICAN, 1909-1977) ATTRIBUTION

About Seller

555 Washington Ave, Ste 129

St. Louis, MO 63101

United States

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $5 |

| $30 | $10 |

| $100 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $3,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $30,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

| $300,000 | $25,000 |

| $500,000 | $50,000 |

About Auction

May 27, 2023

Selkirk's biannual auction features fine art, furniture, sculpture, lighting, rugs, decorative objects and collectibles from MCM through the Contemporary. Selkirk Auctioneers & Appraisers info@selkirkauctions.com

- Lot Description

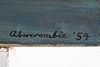

GERTRUDE ABERCROMBIE (AMERICAN, 1909-1977) ATTRIBUTION

Oil on canvas, spuriously signed lower right. The surrealist, folk art scene composed of a woman with an apple below a crescent moon, a set of stairs to a false door before a skeletal tree at the left. Unframed. The attribution by Susan Weininger, Professor Emierita, Lincoln University, who writes: Authentication for Gertrude Abercrombie (attributed), Youth, 1954, 12” x 15 ¾”, oil on masonite, signed and dated lower right.

This painting of a woman in an austere landscape, devoid of anything but a leafless tree and a strange, isolated staircase topped by a door, with a crescent moon and single black bottomed cloud in the dark sky, is made up of elements frequently seen in other paintings by Abercrombie. It does not appear in my extensive records of the artist’s work, nor is there a secure provenance. This does not automatically mean that it is not an authentic work but does require an analysis of the style and content of the painting to determine its authenticity.

There are a number of anomalies in the painting that are immediately apparent, despite the use of many of Abercrombie’s favorite motifs. The figure itself is peculiar in proportion—a very large head atop a short necked, short armed, sway backed body which is fuller than the usual streamlined silhouettes that Abercrombie usually painted. She was not a skillful figure painter and developed a formulaic and characteristic simplified figure type that Youth strives for but fails to execute. The long neck, a distinctive trait in Abercrombie’s conventional self-portraits as well as her representations of herself as a full-length figure is of particular importance (see, for example, Search for Rest [Nile River], 1951, Dijkstra Collection; Dilemma, 1947, Barbara Tannenbaum Collection; Serpentina [Pink Snake Lady] [Lady and Staircase], 1947, private collection; Strange Shadows [Shadows and Substance], 1950, private collection). Abercrombie’s own long neck was exaggerated in her figures, perhaps as a way of lending them an elegance, and creating a sense of proportion in the extreme simplifications of the human form she produced.

The strange, truncated staircase topped by a door in the center of the painting is reminiscent of those in a number of Abercrombie works from the late 1940s, most of which seem to relate to the period when the artist was leaving her first marriage and entering her second. These staircases that are set in a landscape (such as that in Dilemma or Between Two Camps, 1948, private collection) and are symbolic of one path open to the figure, resonating with the new path that Abercrombie was taking in her own life. The staircase in Youth, in contrast to those in the paintings just mentioned, is tiny and culminates in a door that sits at an odd angle to the top of the stairs. While Abercrombie’s figures are often generalized and simplified, her inanimate objects have the beauty of exquisitely conceived three dimensional objects, rendered with great care. She was trained in her very traditional art classes at University of Illinois (some of her class projects are in the collection of the Illinois State Museum, Springfield) to create believable three-dimensional objects with the careful use of light and shade, an effect we see in many of her still life paintings and in the rendering of the staircases in Between Two Camps and Dilemma. The stairs in Youth, if somewhat uneven, are placed at an angle to the picture plane in a believable way, but the door on the top step is parallel to the picture plane (we see it head on, rather than at an angle conforming to the stairs). In the respect for her training that is apparent throughout her career, it is unlikely that Abercrombie would have made this kind of error in consistency. The door itself does not have the usual careful rendering of light and shade that we see in Abercrombie’s innumerable doors—here there is a dark outline around each of the panels of the door, with so sense of light and shade to give a sense of the depth of the panels.

While Abercrombie’s leafless trees are ubiquitous, those in the distance are usually crisp silhouettes, while the one in Youth seems careless and sloppy. And Abercrombie often made use of shadows to increase the sense of solidity of the objects she painted—there are no shadows at all in this work.

This brings us to meaning. The collection of Abercrombie themed motifs in the painting do not seem to add up to anything. Abercrombie’s work is infused with meaning, and the staircase that meant something as one choice at the crossroads of her life does not work in this configuration. It is arbitrarily placed in the center of the painting without any sense of why it is there.

In 1954, Abercrombie was very busy. She had two solo shows in addition to her participation in a number of group exhibitions. The same was true for the years immediately preceding and following. She was extremely productive and recorded the names of numerous paintings done in these years, which makes an unrecorded painting even less likely. In addition, the anomalies of style and the lack of ostensible meaning, along with the lack of secure provenance, lead me to conclude that in my opinion, this is not an authentic Abercrombie.

Stretcher: 12 x 15 3/4 in. (30.5 x 40 cm.)Condition

Any condition statement is given as a courtesy to a client, is an opinion, and should not be treated as a statement of fact. Reference to condition written, oral or within a condition report shall not be regarded as a full account of condition and may not include all defects, alterations, or restorations. Absence of a condition report does not imply a lot is flawless or lacking imperfections or damage. Selkirk Auctioneers & Appraisers shall have no responsibility for any error or omission. Returns shall not be accepted on the basis of condition. - Shipping Info

-

The buyer is responsible for arranging pick-up and shipment of all purchased lots. All registered bidders are responsible for obtaining quotes through in-house shipping or a third-party shipping agent, in advance of bidding. A list of third-party shippers is made available on Selkirk’s website, as well as at the time of invoicing. Not all items are eligible for in-house shipping. Selkirk will not be responsible for any loss, damage, theft, or otherwise responsible for any items left in Selkirk’s possession ten (10) days after the sale. If arrangements for shipping have not been made and communicated within thirty (30) days, Selkirk reserves the right, at this time, to charge a storage fee of $10 per lot per day for furniture and large format items and $5 per lot per day for all other items, and within sixty (60) days, at its own discretion, sell any items left on the premises. Accumulated fees resulting from storage and insurance cost will be taken out of any proceeds. Objects that contain materials of endangered or protected species may be subject to regulations disallowing export and import into other states or countries. It is the buyer’s responsibility to be aware of all applicable laws and regulations and to obtain any required export or import licenses or certificates and any other required documentation.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB