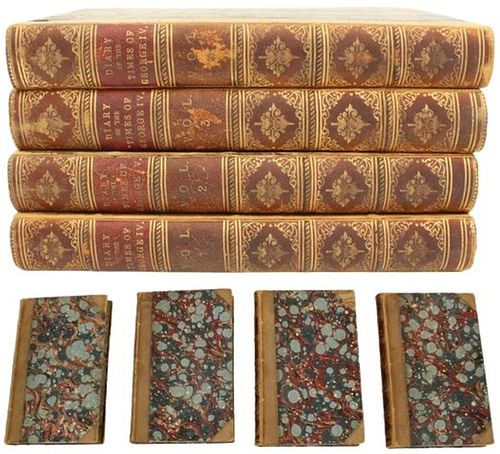

Diary Illustrative of Times of George the 4th

About Seller

522 South Pineapple Avenue

Sarasota, FL 34236

United States

Sarasota Estate Auction specializes in a wide variety of furniture, antiques, fine art, lighting, sculptures, and collectibles. Andrew Ford, owner and operator of the company, has a passion for finding the best pieces of art and antiques and sharing those finds with the Gulf Coast of Florida.

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $10 |

| $100 | $25 |

| $250 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,500 | $250 |

| $7,500 | $500 |

| $20,000 | $1,000 |

| $50,000 | $2,500 |

| $100,000 | $5,000 |

| $250,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Jan 20, 2024

Artists to include: Jorge Blanco, Leonardo Nierman, Picasso, LeRoy Neiman, Darrell Crisp, Francois Krige, Mino Delle Site, Peter Max, Edward Povey, Sky Jones, Robert Rauschenberg, and others. There are also 7 Original Charles Schulz Drawings done by Reuben Timmins, Production Cels, over 200 lots of Important Books and Manuscripts, Sterling Silver, a Jane Kostick Geometric Wooden Sculpture, Modern Design and Furniture, Fantastic Estate Jewelry, and so much more! Sarasota Estate Auction sarasotaestateauction@gmail.com

- Lot Description

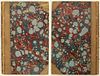

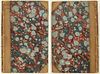

Diary Illustrative of Times of George the Fourth 1838, 1839. This four-volume set of books is titled “Diary Illustrative Of the Times of George the Fourth, Interspersed with Original Letters from The Late Queen Caroline, And from Various Other Distinguished Persons”. The first two volumes were published in 1838 and two further volumes were added in 1839, the books were published in London by Henry Colburn and written by Lady Charlotte Campbell, who later became Lady Bury, and this is a complete first edition set of the Diary. Lady Charlotte Susan Maria Bury (1775 - 1861) was an English novelist, chiefly remembered in connection with this title. In 1796 she married Colonel John Campbell, they had nine children together, but only two survived. John died in 1809 and Charlotte remarried in 1818 and became Lady Charlotte Susan Maria Bury; she was appointed a lady-in-waiting in the household of Caroline of Brunswick, the Princess of Wales. It is believed that Charlotte kept a diary, in which she recorded the foibles and doings of the princess and other members of the court. The diary was published anonymously later on and the identity of its author was revealed in the Edinburgh Review; Lady Charlotte was rumored to have received a thousand pounds from the publisher. Soap opera time. The diary was a big success and several editions were printed and sold out in a few weeks, and you just need to know some things about George IV to understand why the books sold so well. In April 1795, Prince George of Wales, the first son of King George III, reluctantly married his first cousin, Princess Caroline of Brunswick. It was not a happy union. George was a womanizer and already married to someone else, having wed Maria Fitzherbert ten years earlier; she was a Catholic, and as a Catholic, that marriage did not legally count, and he was having an affair with Frances Villiers, Lady Jersey, too, so the marriage between George and Caroline was strained from the very beginning. Caroline and George reportedly spent only two nights together before separating, but in this short time, they conceived a child, Princess Charlotte of Wales, who was born in January 1796, almost exactly nine months after the wedding. In April 1796, George wrote to Caroline to set terms of their separation. By the 1800’s, Caroline was living at a private residence in Greenwich Park. While there, rumors began to circulate of Caroline’s alleged immoral and immodest behavior. These rumors originated largely from her neighbor, Lady Douglas, who claimed that Caroline had given birth to an illegitimate son and had taken part in lewd and inappropriate behavior, including sending anonymous letters with obscene drawings to to the residence of Lady Douglas. In 1806, a commission was set up to investigate the claims, known as the “Delicate Investigation”. Ultimately, the investigation found no evidence to prove the claims of Lady Douglas. Was this a set up by George to get rid of Caroline? Caroline remained married to George, but from the outset the marriage was never going to be a success. His womanizing, his marriage to a Catholic, his affair with another woman - and George only consented to marrying Caroline because his father, King George III, agreed to pay off all of the Prince’s considerable debts if he did - and when the marriage broke down very publicly in 1820, it scandalized the nation. More background: in 1820, after the death off his father, George IV succeeded to the throne, and as soon as George became King, Caroline immediately returned to claim her place as Queen of England. Outraged, George sought a divorce and pressured Parliament to write a bill to get rid of her - the bill would strip Caroline of her title and end their marriage by Act of Parliament. (A divorce through the ecclesiastical courts was difficult for the King because of his own embarrassing, scandalous love life, so the bill in Parliament was considered the easiest way to obtain a divorce, and passage of the bill became a spectacular cause celebre.) Caroline was put on trial for adultery; it was not actually a trial, but a parliamentary debate on the bill designed to grant the King a divorce. She attended Westminster on a daily basis to hear the MP’s debate her fate, the House of Lords heard evidence of the Queen's adultery, she was often depicted as a heroine alongside that great symbol of English liberty, the Magna Carta, and with public opinion strongly in her favor, the measure was ultimately withdrawn. The government was also afraid of a public uprising. With memories of the French Revolution still vivid in their minds, many of the government ministers were concerned that public outrage at the trial might lead to insurrection, and Lord Liverpool, the Prime Minister, announced that the bill would be dropped, leading to country-wide celebrations in the Queen’s favor. Caroline’s victory was short lived. Following the “trial”, Caroline accepted the government’s offer of an allowance of £50,000 a year if she went to live abroad quietly, but within a year she died following a short illness. All this played out in the open, in the public eye, and it brought into focus the hypocrisy of the king and his attempt to rule and have his cake and eat it too. The books are 3/4 bound, with five raised bands, six gilt-ruled compartments with red labels, gilt lettering, and gilt decorations on the spine, marbled boards, marbled endpapers with the bookplate of James C Peasley [Paisley?] on the front paste-downs, and all the edges are marbled. Volume I has ”By Lady Charlotte Campbell afterwards Lady Bury” in pencil on the title page, the date in Roman numerals [MDCCCXXXVIII], then a one-page Advertisement, 391 pages of text, and an Errata page at the rear; Volume II is dated MDCCCXXXVIII [1838] and has 415 pages of text, with an ad for two books published by Mr. Colburn at the rear; Volume III is edited by John Galt and has a half-title, a frontis portrait of the Princess of Wales with a tissue guard, and is dated MDCCCXXXIX [1839] on the title page, with a seven-page Preface and 402 pages of text, and the last volume is also edited by John Galt and dated MDCCCXXXIX and has 392 pages of text. The books also had different printers: the first volume was printed by G. Woodfall on Skinner Street in London, the second one was printed by William Wilcockson at the Rolls Building, the third volume by Ibotson and Palmer on Savoy Street in the Strand, and the last volume by J. B. Nichols and Son on Parliament Street, and the books are uniformly bound, even with all the different printers. The books are 8vo. and measure 8 3/4 x 5 3/4 in. wide, with tight bindings and rather clean pages and text; there are faint brown spots in the margins here and there, and some spots on the last couple of pages in the second volume, and overall clean pages and text. There are penciled notes to show people’s names in some places (to identify the people) and light rubbing on the spines, along some of the edges of the boards, and at the tips, with wear on a leather tip and at the top of a marbled board on Volume III, faded spines, and a loose tissue guard with the portrait of the Princess of Wales in Volume III, and a rare complete set of the first editions. We only found one complete set of first editions offered for sale on the rare book website we use and it goes for $500, and we believe the one we have for auction is comparable to that one. It was an unprecedented time in British history that pitted King against Queen and a corrupt man versus a wronged woman, and a bestseller in the 1800’s. #194 #1570

- Shipping Info

-

SHIPPING INFORMATION·

Sarasota Estate Auction IS NOT RESPONSIBLE FOR SHIPPING. All shipping will be handled by the winning bidder. Sarasota Estate Auction recommends obtaining shipping quotes before bidding on any items in our auctions. If you are interested in obtaining any information on local shippers, please send us an email and we will kindly send you a list of local shippers. Refunds are not offered under any circumstances base on shipping issues, this is up to the buyer to arrange this beforehand.

Premier Shipping, info@premiershipment.com

BIDDER MUST ARRANGE THEIR OWN SHIPPING. Although SEA will NOT arrange shipping for you, we do recommend our shipper Premier Shipping & Crating at info@premiershipment.com You MUST email them, please do not call. If you'd like to compare shipping quotes or need more options, feel free to contact any local Sarasota shippers. You can email any one of the shippers below as well. Be sure to include the lot(s) you won and address you would like it shipped to. Brennan with The UPS Store #0089 - 941-413-5998 - Store0089@theupsstore.com AK with The UPS Store #2689 - 941-954-4575 - Store2689@theupsstore.com Steve with The UPS Store #4074 - 941-358-7022 - Store4074@theupsstore.com Everett with PakMail - 941-751-2070 - paktara266@gmail.com

-

- Payment & Auction Policies

-

Available payment options

We accept all major credit cards, wire transfers, money orders, checks and PayPal. Please give us a call at (941) 359-8700 or email us at SarasotaEstateAuction@gmail.com to take care of your payments.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB