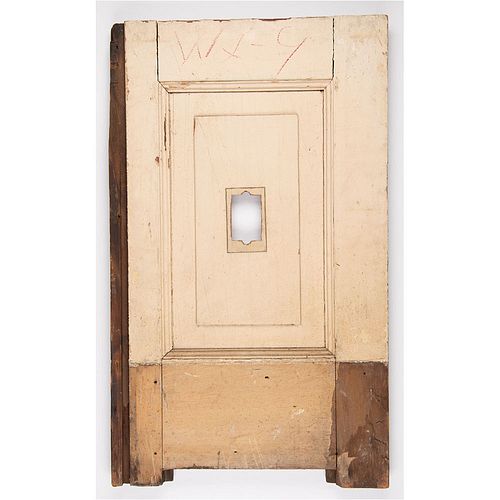

White House Wall Panel Section with Electrical Outlet Cutout

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $5 |

| $50 | $10 |

| $200 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

About Auction

Nov 8, 2023

RR Auction's November Fine Autographs and Artifacts auction offers an extraordinary and wide-ranging selection of the rare and remarkable. RR Auction support@rrauction.com

- Lot Description

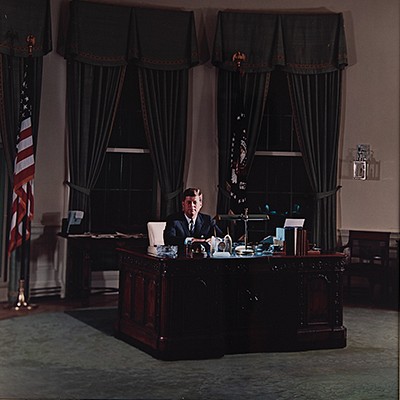

Unique wall panel from the White House, measuring 19.5″ x 32″ x 1.5″, featuring a central rectangular panel with a cut-out for an electrical outlet. The front is painted in a traditional off-white color and is annotated in red grease pencil across the top rail. Electricity was first installed in the White House during Benjamin Harrison's administration in 1891. Irwin 'Ike' Hoover, an electrician who later became White House Chief Usher, recollected that 'the Harrison family were actually afraid to turn the lights on and off for fear of getting a shock‰Û_I would turn on the lights in the halls and parlors in the evening and they would burn until I returned the next morning to extinguish them.' In very good to fine condition, with some chipping to paint. Originates from the Knipp & Co. 'contractor's salvage' resulting from their work in the renovation of the White House during the Truman administration. Accompanied by a letter of authenticity from historian and collector Wayne Smith, author of White House Renovation Souvenirs. Also includes a signed hardcover copy of the book.

The Baltimore-based architectural woodworking firm Knipp & Co. was chosen as a subcontractor for President Harry S. Truman's renovation and restoration of the White House, which took place between 1948 and 1952. Their work is discussed in the article 'White House 'Contractor's Salvage' Revived' by Barbara D. McMillan: "Knipp & Company was very much on the scene during the dismantling of the house. It hauled away moldings, architectural elements, wood floors, and even lath under the plaster for the general contractor, who began work on December 13, 1949‰Û_It was President Truman’s stated intention to save 'all the doors, mantels, mirrors and things of that sort so that they will go back just as they were.' Architect Lorenzo S. Winslow also 'appreciated the old, and from the outset urged the careful conservation and reuse of paneling, window sash, molding and doors.' These intentions, however, were not fully realized. Some of the wood was damaged upon removal, and some was stylistically inappropriate as Winslow tried to adapt the White House interior to the time of its original architect, James Hoban‰Û_Franklin Knipp, who became president of the firm in 1964, stressed that most of the removed millwork from the White House arrived to them unmarked, with nothing to indicate where it had come from, unless it was from a 'primary' room (a State Room) or one that was to be reconstructed, such as the State Dining Room."

As the White House renovations came to a close, the Commission on the Renovation of the Executive Mansion, with the approval of President Truman, established a 'souvenir program' to dispose of excess raw materials removed from the Executive Mansion, such as bricks, nails, plaster, and wooden relics. McMillan reports: "White House moldings that were not reused in the White House reconstruction but left stored with the Knipp firm were originally intended by the firm to be returned to the White House, until at last Major General Glen E. Edgerton, the government’s representative on the work, ordered Knipp to stop bringing back the old wood." This 'contractor's salvage' subsequently remained in Franklin Knipp's custody for decades; he subsequently offered them as gifts to friends, and repurposed items for use in his own home on Maryland's Gibson Island. - Shipping Info

-

Bidder is liable for shipping and handling and providing accurate information as to shipping or delivery locations and arranging for such. RR Auction is unable to combine purchases from other auctions or affiliates into one package for shipping purposes. Lots won will be shipped in a commercially reasonable time after payment in good funds for the merchandise and the shipping fees are received or credit extended, except when third-party shipment occurs. Bidder agrees that service and handling charges related to shipping items which are not pre-paid may be charged to a credit card on file with RR Auction. Successful international Bidders shall provide written shipping instructions, including specified Customs declarations, to RR Auction for any lots to be delivered outside of the United States. NOTE: Declaration value shall be the item’(s) hammer price and RR Auction shall use the correct harmonized code for the lot. Domestic Bidders on lots designated for third-party shipment must designate the common carrier, accept risk of loss, and prepay shipping costs.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB