Steve Jobs Handwritten Technical Instructions and Annotated Schematics (1971)

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $5 |

| $50 | $10 |

| $200 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

About Auction

Mar 16, 2023

RR Auction support@rrauction.com

- Lot Description

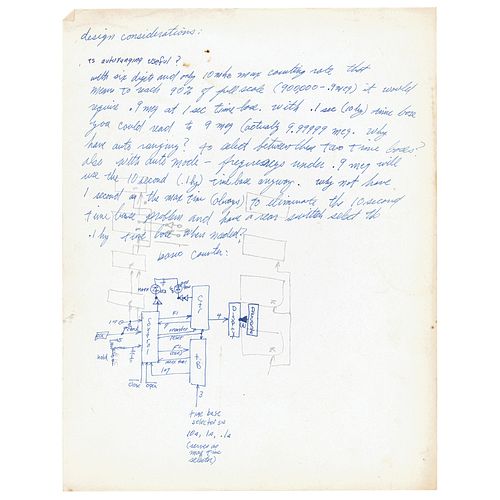

Fascinating early handwritten technical instructions and schematic annotations by Steve Jobs from circa 1971, unsigned, penned on two off-white sheets, 8.5 x 11 and 11 x 8.5, which contain Jobs’ telltale cursive handwriting in addition to instances of print handwriting and annotated diagrams. The first sheet, headed “design considerations,” features a paragraph of technical observations penned by Jobs above a small schematic labeled “basic counter.” The instructions read: “TS autoranging useful? With six digits and only 10 mhz max counting rate that means to reach 90% of full scale (900,000-.9 meg) it would require .9 meg at 1 sec time base, with .1 sec (10 hz) time base you could read to 9 meg (actually 9.99999 meg. Why have auto ranging? To select between these two time bases? Also with auto mode—frequencys under .9 meg will use the 10 second (.1 hz) time base anyway. Why not have 1 second as the max time (always) to eliminate the 10 second time base problem and have a rear switch select the .1 hz time base when needed?” While it remains uncertain if Jobs drew out the diagram, it is confirmed that he did add a few notes below, “10s, 1s, .1s, (serves as max time selector).” The second sheet consists of a large hand-drawn schematic featuring numerous handwritten annotations, the majority of which are in print and a few others in Jobs’ instantly identifiable slanted cursive; the latter read: “digit address (6),” “or possible shift register,” and “decimal point lines (6).”

According to Apple historian Corey Cohen, the instructions and diagrams appear to be for a digital counting mechanism, one perhaps similar to the type found in a waiting room. The idea and conventions of a “basic counter” would be something familiar to Jobs, who was likely well-acquainted with the needs and demands of such a device through his father, Paul, who worked at a car dealership fixing and selling vehicles. Coincidentally, Jobs would later modify an Apple-1 computer (currently owned by J.B. Pritzker) to act as a display at an auto shop that would reveal the customer number of the most recently serviced vehicle. Also includes a third 11 x 8.5 sheet dated October 30, 1971, which consists of a photocopy of a schematic done by an unknown draftsman. In overall fine condition, with some toning and edgewear, most notable to the larger schematic sheet.

RR Auction has, for lack of greater evidence, deemed the penmanship of the schematics themselves as inconclusive. Jobs may have written only sections of these two documents (the portions in script), or he may have composed both the documents and the schematics in their entirety. Determining as much would require not only examples of Jobs’ print handwriting from this period, but also his past hand-drawn diagrams or schematics, all of which are virtually unobtainable. That Jobs actually did know how to create and draw such schematics was, according to his former Atari boss Allan Alcorn, not out of the question: ‘When I hired Steve, in ‘73, it was as a technician to work with an engineer to build prototypes from schematics the engineers drew. He was able to successfully do that, and I suppose he also got his skills working with Woz when they were in high school.’

Public perception has long cast Steve Jobs under a spotlight that now, with the emergence of these remarkable handwritten documents, feels utterly restrictive. Half showman and half businessman, Jobs excelled in his role as Apple’s CEO and spokesperson, regaling packed auditoriums with tech launches that excited the masses with the promise of tomorrow. But he was more than just the face of Apple. Jobs held a keen understanding of engineering and backend development that few knew he possessed, traits made evident by these never-before-seen specialized notes and diagrams. A rare treasure that offers unique insight into the little-known technical acumen of Apple’s Steve Jobs. - Shipping Info

-

Bidder is liable for shipping and handling and providing accurate information as to shipping or delivery locations and arranging for such. RR Auction is unable to combine purchases from other auctions or affiliates into one package for shipping purposes. Lots won will be shipped in a commercially reasonable time after payment in good funds for the merchandise and the shipping fees are received or credit extended, except when third-party shipment occurs. Bidder agrees that service and handling charges related to shipping items which are not pre-paid may be charged to a credit card on file with RR Auction. Successful international Bidders shall provide written shipping instructions, including specified Customs declarations, to RR Auction for any lots to be delivered outside of the United States. NOTE: Declaration value shall be the item’(s) hammer price and RR Auction shall use the correct harmonized code for the lot. Domestic Bidders on lots designated for third-party shipment must designate the common carrier, accept risk of loss, and prepay shipping costs.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB