Stephen Hawking TLS on Black-Body Radiation and Geodesic Incompleteness

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $5 |

| $50 | $10 |

| $200 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

About Auction

May 10, 2023

RR Auction support@rrauction.com

- Lot Description

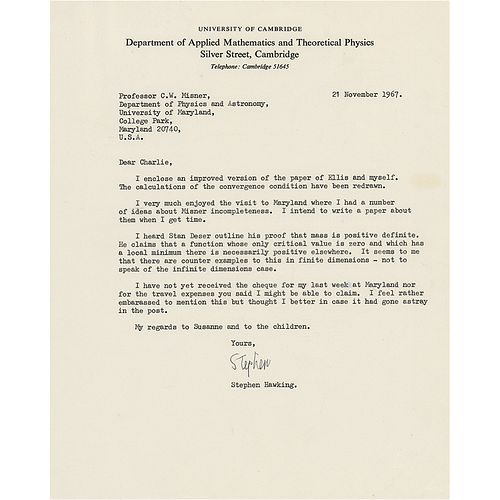

TLS signed “Stephen,” one page, 8 x 10, University of Cambridge letterhead, November 21, 1967. Letter to physicist Charles W. Misner, a professor at the University of Maryland, with reference to an improved version of a paper that Hawking co-authored with George Ellis (‘The Cosmic Black-Body Radiation and the Existence of Singularities in Our Universe,’ The Astrophysical Journal, Vol. 152, April 1968). In part: "I enclose an improved version of the paper of Ellis and myself. The calculations of the convergence condition have been redrawn. I very much enjoyed the visit to Maryland where I had a number of ideas about Misner incompleteness. I intend to write a paper about them when I get time. I heard Stan Deer outline his proof that mass is positive definite. He claims that a function whose only critical value is zero and which has a local minimum there is necessarily positive elsewhere. It seems to me that there are counter examples to this in finite dimensions—not to speak of the infinite dimensions case." In fine condition, with a faint paperclip impression to the top edge.

Stephen Hawking first met the American physicist Charles W. Misner during the latter’s 1966-67 visit to Cambridge at the invitation of Hawking’s postgraduate supervisor Dennis Sciama; the two became close, and Hawking visited Misner at his own institution, the University of Maryland, at the end of 1967. Hawking’s work on singularity theorems, which he first published in his 1965 doctoral thesis, overlapped with the research Misner was undertaking on geodesic incompleteness, a notion at the centre of the concepts Hawking was developing with Roger Penrose (the ‘Penrose-Hawking singularity theorems’). Here, Hawking seemingly refers to a proof that another of their colleagues in the field, Stanley Deser, would publish the following year in the Physical Review Letters, in a paper entitled ‘Positive-Definiteness of Gravitational Field Energy.’

Diagnosed with early-onset motor neurone disease in 1963, Hawking’s physical capabilities deteriorated over time—his shaky hand evinced in this signature of just four years later—making authentic autographs exceedingly scarce. Confined to a wheelchair by the end of the 1970s, he opted to sign with just a thumbprint later in life. A marvelous letter by the celebrated theoretical physicist, rife with scientific content. - Shipping Info

-

Bidder is liable for shipping and handling and providing accurate information as to shipping or delivery locations and arranging for such. RR Auction is unable to combine purchases from other auctions or affiliates into one package for shipping purposes. Lots won will be shipped in a commercially reasonable time after payment in good funds for the merchandise and the shipping fees are received or credit extended, except when third-party shipment occurs. Bidder agrees that service and handling charges related to shipping items which are not pre-paid may be charged to a credit card on file with RR Auction. Successful international Bidders shall provide written shipping instructions, including specified Customs declarations, to RR Auction for any lots to be delivered outside of the United States. NOTE: Declaration value shall be the item’(s) hammer price and RR Auction shall use the correct harmonized code for the lot. Domestic Bidders on lots designated for third-party shipment must designate the common carrier, accept risk of loss, and prepay shipping costs.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB