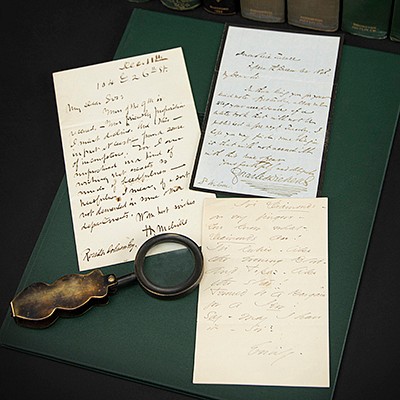

Simon Bolivar and Francisco de Paula Santander Document Signed

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $5 |

| $50 | $10 |

| $200 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

About Auction

Oct 12, 2022

RR Auction support@rrauction.com

- Lot Description

Rare manuscript DS in Spanish, signed “Bolivar” and "Fr. P. Santander," one page on Colombian Republic letterhead, 7.75 x 9.5, December 7, 1820. Official letter from Vice President Francisco de Paula Santander to President Simon Bolivar, which reads (translated): “Mr. Alberto Salazza has placed before this Government the representations and documents I enclose; as these bear no character of legality, and as I have no battalion that I might give him, I await action by His Excellency the Liberator to decide the Matter.” Bolivar responds on January 3, 1821, with a short note penned in another hand: “The Govt. renders thanks to this individual for his services in its defense; as to the pay, this is not in order, there being others with years of service who have received no pay.” Signed at the conclusion of their respective messages by both Bolivar and Santander. In fine condition, with scattered light creasing and soiling. Accompanied by a full English translation. Documents signed by both Colombian liberators are quite rare.

Santander met Simon Bolivar in 1812 at age 20 and fought under his command for many years. At the age of 27, he was elected as vice president of Gran Colombia, a federal republic that encompassed a large part of Northern South America. Although president, Bolivar preferred to be in the field, and during his extensive absences, his responsibilities fell on the young vice president’s shoulders. The acting president by constitutional law, Santander sent trade missions around the world and convinced Great Britain and the United States to recognize Gran Colombia as a state. Santander’s loyalties lay with Nueva Granada, the northern part of Gran Colombia, and what would now be considered Colombia geographically.

Bolivar and Santander were considered good friends and political allies for many years before their differing ideologies pushed them apart. Their differing points of view over the future of Gran Colombia—namely Bolivar’s strong belief in a unified South American state—soon created an irreparable rift between the two, which set off a string of political events that marked the destiny of the newly liberated Spanish colonies. In 1828, Bolivar declared himself dictator and abolished the Vice President position, in turn effectively cutting off Santander from all political power and influence. A month later there was an assassination attempt on Bolivar’s life. Santander was accused, captured, found guilty, and sentenced to death. However, Bolivar pardoned him and commuted his sentence to exile. Santander denied his involvement but, later in his life, admitted that he knew that an assassination plan was in the works. - Shipping Info

-

Bidder is liable for shipping and handling and providing accurate information as to shipping or delivery locations and arranging for such. RR Auction is unable to combine purchases from other auctions or affiliates into one package for shipping purposes. Lots won will be shipped in a commercially reasonable time after payment in good funds for the merchandise and the shipping fees are received or credit extended, except when third-party shipment occurs. Bidder agrees that service and handling charges related to shipping items which are not pre-paid may be charged to a credit card on file with RR Auction. Successful international Bidders shall provide written shipping instructions, including specified Customs declarations, to RR Auction for any lots to be delivered outside of the United States. NOTE: Declaration value shall be the item’(s) hammer price and RR Auction shall use the correct harmonized code for the lot. Domestic Bidders on lots designated for third-party shipment must designate the common carrier, accept risk of loss, and prepay shipping costs.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB