Samuel L. Clemens 26-Page Autograph Letter Signed to His Wife on Christmas Day

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $5 |

| $50 | $10 |

| $200 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

About Auction

May 15, 2024

Boasting nearly 800 lots, RR Auction's May Fine Autographs and Artifacts sale is highlighted by a section honoring the anniversary of President John F. Kennedy's birth—including important signed photographs, a remarkable Kennedy family-signed book, a knife used to slice his inaugural cake, a page from his pioneering Peace Corps legislation, and scarce teletype reports on his assassination. RR Auction support@rrauction.com

- Lot Description

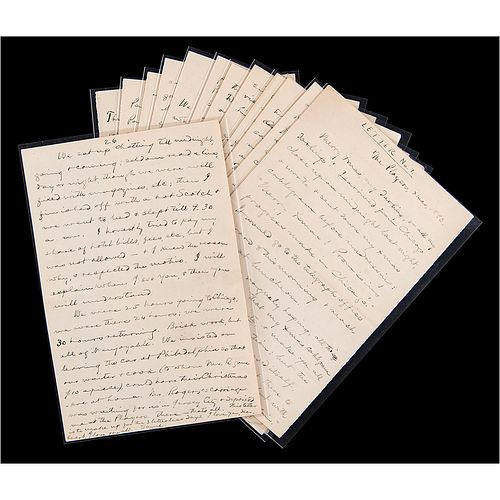

ALS signed “Sam'l,” thirteen pages both sides, 5.5 x 8.25, December 25, 1893. Incredibly long handwritten letter to his wife Livy, written on Christmas Day from The Players, a social club in New York City, upon Clemens' return from Chicago. He had traveled there with his friend and benefactor, Standard Oil industrialist Henry Huttleston Rogers, to negotiate a new contract with James W. Paige, the inventor of a typesetting machine in which Clemens had invested heavily—a failed venture that would practically bankrupt the great author.

Clemens divides the letter into sections—"Letter No. 1" through "Letter No. 4"—to make up for the "3 letterless days" during his trip. In them, he provides a detailed, creative narration—with extensive, Twainian dialogue—of his business meetings in Chicago, as well as sending Christmas wishes, family news, and particulars of his travels.

In part: "Merry Xmas, my darling, & all my darlings! I arrived from Chicago close upon midnight last night, & wrote & sent my Xmas cablegram before undressing: 'Merry Xmas! Promising progress made in Chicago'...I was vaguely hoping, all this past week that my Xmas cablegram would be definite, & make you all jump with jubilation; but the thought always intruded itself, 'You are not going out there to negociate with a man, but with a louse. This makes results uncertain.' I was asleep as Christmas struck upon the clocks at midnight, & didn't wake again till two hours ago...I have had my coffee & bread, & shan't get out of bed till it is time to dress for Mrs. Laffan's Xmas dinner this evening—where I shall meet Bram Stoker & must make sure about that photo with Irving's autograph...In order to remember, & not forget—well, I will go there with my dress coat wrong side out; it will cause remark & then I shall remember...

I tell you it was interesting! The Chicago campaign, I mean. On the way out Mr. Rogers would plan-out the campaign while I walked the floor & smoked and assented. Then he would close it up with a snap & drop it & we would totally change the subject & take up the scenery, etc. Then a couple of hours before entering Chicago, he said: 'Now we will review, & see if we exactly understand what we will do & will not do—that is to say, we will clarify our minds, & make them up finally. Because in important negociations a body has got to change his mind: & how can he do that if he hasn't got it made up, & doesn't know what it is.' A good idea, & sound. Result—two or three details were selected & labeled (as one might say), 'These are not to be yielded or modified, under any stress of argument, barter, or persuasion.' There were a lot of other requirements—all perfectly fair ones, but not absolute requisites. 'These we will reluctantly abandon & trade off, one by one, concession by concession, in the interest of & for the preservation of those others—those essentials.' That was clear & nice & easy to remember. One could dally with minor matters in safety—one would always know where to draw the line."

Clemens goes on to narrate, at great length, the specifics of a late-night meeting involving himself, Charley Davis and Mr. Dewey (a banker), as well as Paige's attorney, Mr. Walker, "the ablest lawyer in the West, a fine & upright gentleman; thoroughly despised his client, but would protect him sternly." Discussing the In part: "Had Clemens better go? This was discussed. Stone & Dewey finally said yes, but with this proviso: that Walker must not reveal to Paige at next morning's conference (where Paige himself would be present) that Clemens was here in Chicago meddling. Stone & Dewey said Walker had a fine library, was a man of wide literary affections, & a visit from me could hardly fail to have a good effect...As to next morning's conference, Clemens would not be there, of course. So we drove to Walker's—a sumptuously equipped dwelling...Mr. Rogers began in a low voice & very deferentially, & gradually unfolded & laid bare our list of requirements. Toward the last it was visibly difficult for Mr. Walker to hold still. When at last it was his turn he said in his measured & passionless way, but with impatience visibly oozing our of the seams of his clothes—'I may as well be frank with you, gentlemen: Mr. Paige will never concede one of these things. Here is a proposed company of $5,000,000. Mr. Paige consented to be reduced to a fifth interest. That seems to me to be concession enough. I cannot & must not advise him to consent to these restrictions'...Mr. Rogers gradually broke down Mr. Walker's objections, one after the other till there was nothing left but his idea that in fairness Paige was not getting enough...Then Mr. Walker turned toward me & said: 'Mr. Clemens, I've read every line you ever wrote, & I want more. I make you this offer: I will advise & urge Paige to concede every requirement that has been asked here to-night, provided you'll write another book.' That was his badinageous way of conveying to the conference what he had really made up his mind to do. I promised the book."

The following morning, Clemens's representatives went to the meeting with Paige and Walker, which he discusses in "Letter No. 3." In part: "As usual, Mr. Rogers was required to do all of the talking for our side, & he did it. At the end of an hour Paige had retired from position after position until he had conceded every detail but one; & it was there he took his stand. It was the matter of stipend. He was offered $5,000 a year till his dividends should aggregate $100,000...He said he could not live on it...That ended the Chicago campaign. There was nothing overlooked or left undone that could have been done, except the raising of Paige's stipend to his fancy figure of $3,000 a month—& we were all opposed to that. The waiting game has been my pet notion from the beginning. I want it played till it breaks Paige's heart...As far as I can see, Paige is the only one who can't wait; to him, time is shod with lead; every day, now, adds to his gray hairs, & spoils his sleep. I am full of pity & compassion for him, & it is sincere. If he were drowning I would throw him an anvil."

In "Letter No. 4," Clemens documents his journey to and from Chicago: "We had nice trips, going & coming. Mr. Rogers had telegraphed the Pennsylvania Railroad for a couple of sections for us in the fast train...The Vice President telegraphed back that every berth was engaged (which was not true—it goes without saying) but that he was sending his own car for us. It was mighty nice & comfortable. In its parlor it had two sofas, which could become beds at night. It had four comfortably cushioned cane arm chairs. It had a very nice bedroom with a wide bed in it; which I said I wanted to take because I believed I was a little wider than Mr. Rogers—which turned out to be true, so I took it. It had a darling back porch—railed, roofed & roomy; & there we say, most of the time & viewed the scenery & talked, for the weather was May weather, & the soft dream-pictures of hill & river & mountain & sky were clear & away beyond anything I have ever seen for exquisiteness & daintiness...We were 25 hours going to Chicago; we were there 24 hours; we were 30 hours returning. Brisk work, but all of it enjoyable." In fine condition. Accompanied by the torn original mailing envelope, addressed by Clemens to "Mrs. S. L. Clemens" in Paris, France.

Despite Paige's eventual agreement to the new contract, Samuel Clemens's involvement in the typesetting machine was to be totally ill-fated. At the end of 1894, after Paige's machine did disastrously in a long test run with other typesetting machines, Clemens was advised by Rogers to give up any hopes for its commercial success. The eventual winner in the typesetting derby was to be the Linotype; Clemens simply backed the wrong horse, at a cost of $300,000—most of his book profits, as well as a large portion of his wife's inheritance—plus fifteen years of effort. Many point to Clemens's over-investment in the Paige typesetter as the cause of not only his family's financial decline, but also the decline of his wit and humor. - Shipping Info

-

Bidder is liable for shipping and handling and providing accurate information as to shipping or delivery locations and arranging for such. RR Auction is unable to combine purchases from other auctions or affiliates into one package for shipping purposes. Lots won will be shipped in a commercially reasonable time after payment in good funds for the merchandise and the shipping fees are received or credit extended, except when third-party shipment occurs. Bidder agrees that service and handling charges related to shipping items which are not pre-paid may be charged to a credit card on file with RR Auction. Successful international Bidders shall provide written shipping instructions, including specified Customs declarations, to RR Auction for any lots to be delivered outside of the United States. NOTE: Declaration value shall be the item’(s) hammer price and RR Auction shall use the correct harmonized code for the lot. Domestic Bidders on lots designated for third-party shipment must designate the common carrier, accept risk of loss, and prepay shipping costs.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB