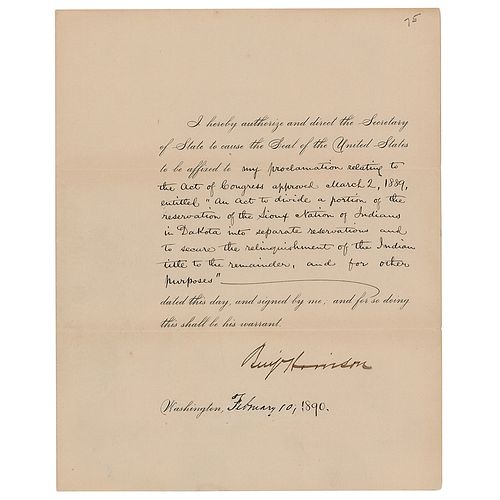

President Benjamin Harrison Approves the Sioux Act of 1889, Transferring 9,000,000 Acres Into Federal Ownership

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $5 |

| $50 | $10 |

| $200 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

About Auction

Sep 13, 2023

RR Auction support@rrauction.com

- Lot Description

Partly-printed DS as president, signed “Benj. Harrison,” one page, 8 x 10, February 10, 1890. President Harrison authorizes and directs "the Secretary of State to cause the Seal of the United States to be affixed to my proclamation relating to the Act of Congress approved March 2, 1889, entitled ‘An Act to divide a portion of the reservation of the Sioux Nation of Indians in Dakota into separate reservations and to secure the relinquishment of the Indian title to the remainder, and for other purposes.’” Signed boldly at the conclusion by Benjamin Harrison. In fine condition. This document pertains to the proclamation of the Sioux Act of 1889, which further reduced the Great Sioux Reservation by dividing it into six separate reservations. This law was one of three that were significant in forever altering the physical and cultural landscape of South Dakota.

As quoted from historian Herbert T. Hoover’s book The Sioux Agreement of 1889 and Its Aftermath: ‘Sioux people ceded most of the area contained by the boundaries of South Dakota to the United States in three transactions. The Treaty of Washington, D.C, in 1858 provided for a transfer of 11,155,890 acres east of the Missouri River and the settlement of the Yankton Sioux on a reservation containing 430,000 acres near Fort Randall, plus their continued ownership of 648.2 acres at the pipestone quarry in southwestern Minnesota. The Sioux Agreement approved on 28 February 1877 reduced the Great Sioux Reservation (established in one state and three territories west of the Missouri River by the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868) from approximately 60 million to slightly less than 22 million acres. For the next twelve years, the Great Sioux Reservation was situated mainly within present-day South Dakota borders between the northern boundary of Nebraska and the south fork of the Cannonball River, and from the Missouri to a western borderline on the 103rd meridian jutting eastward along the main forks of the Cheyenne River. The Sioux Agreement of 2 March 1889 reduced this reservation by 9,274,668.7 acres, leaving to the Teton and Yanktonai tribes only 12,681,911 acres within the boundaries of the Cheyenne River, Crow Creek, Lower Brule, Pine Ridge, Rosebud, and Standing Rock reservations.

Through the three transactions, the Yanktons, Yanktonais, and seven tribes of Tetons lost their rights to use nearly 58,695,000 acres across the upper Missouri River drainage basin and retained only 13,111,911 acres in South Dakota, plus approximately a section of land surrounding the pipestone quarry in Minnesota. In other words, after three decades of negotiations they retained only 18.3 percent and relinquished 81.7 percent of their land to federal officials who represented a constituency of non-Indians that demanded access to natural resources and space for new arrivals as annual immigration approached its zenith in national history.

All three land transactions came during an era of armed conflict in Sioux Country that opened with the Grattan Affair of 1854 near Fort Laramie in present day Wyoming and closed at the death of Sitting Bull and the tragedy at Wounded Knee, South Dakota, in 1890. Given this situation, tribal representatives acceded to demands for land cession under some duress if not a threat of attack during intermittent war. In response to demands from a burgeoning white population, federal representatives negotiated to confine Sioux people on reservations in order to open ‘surplus’ areas for business development and agrarian settlement.’ - Shipping Info

-

Bidder is liable for shipping and handling and providing accurate information as to shipping or delivery locations and arranging for such. RR Auction is unable to combine purchases from other auctions or affiliates into one package for shipping purposes. Lots won will be shipped in a commercially reasonable time after payment in good funds for the merchandise and the shipping fees are received or credit extended, except when third-party shipment occurs. Bidder agrees that service and handling charges related to shipping items which are not pre-paid may be charged to a credit card on file with RR Auction. Successful international Bidders shall provide written shipping instructions, including specified Customs declarations, to RR Auction for any lots to be delivered outside of the United States. NOTE: Declaration value shall be the item’(s) hammer price and RR Auction shall use the correct harmonized code for the lot. Domestic Bidders on lots designated for third-party shipment must designate the common carrier, accept risk of loss, and prepay shipping costs.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB