President Andrew Johnson Proclaims the First Pact of the 1867 Medicine Lodge Treaty

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $5 |

| $50 | $10 |

| $200 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

About Auction

Mar 13, 2024

RR Auction's March 2024 Fine Autographs and Artifacts auction features 650+ rare and remarkable items. The sale is highlighted by a robust selection of original animation artwork, including Eyvind Earle's remarkable landscape panoramas, Mary Blair's whimsical concept paintings, and production cels from Walt Disney classics like Snow White, Pinocchio, Lady and the Tramp, Peter Pan, and Cinderella. RR Auction support@rrauction.com

- Lot Description

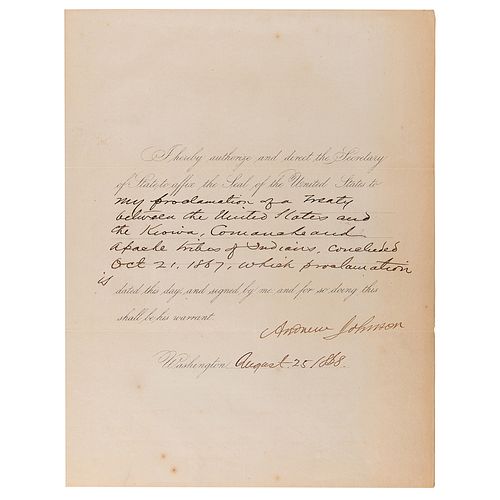

Partly-printed DS as president, one page, 8.5 x 11, August 25, 1868. President Johnson directs the Secretary of State to “affix the Seal of the United States to my proclamation of a Treaty between the United States and the Kiowa, Comanche and Apache tribes of Indians, concluded Oct. 21, 1867.” Signed neatly at the conclusion by Andrew Johnson. The document is affixed by its left edge inside a presentation folder that also contains a printed copy of the ‘Treaty with Kiowa and Comanche, 1867.’ In fine condition, with a bit of scattered foxing.

This document refers to Johnson’s proclamation of the first part of the Medicine Lodge Treaty, the overall name for three treaties signed near Medicine Lodge, Kansas, between the Federal government of the United States and southern Plains Indian tribes. The unified goal was to stop the bloodshed between the parties, which included massacres at Whitestone Hill, Sand Creek, and Pawnee Fork, and various retaliatory raids on U.S. settlements.

Situated deep into the tribes’ hunting grounds, government delegates were met by more than 5,000 representatives of the Kiowa, Comanche, Arapaho, and Kiowa-Apache nations. Two weeks later, members of the Southern Cheyenne joined them as well. The first treaty was signed on October 21, 1867, with the Kiowa and Comanche tribes; the second, with the Kiowa-Apache, was signed on the same day; and the third treaty, with the Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho, was signed on October 28th.

Per the Smithsonian Magazine, historians have since deemed Medicine Lodge Creek as one of the Plains Indians’ most devastating treaties, in large part due to its brief observance. ‘The treaty offered a 2.9-million-acre tract to the Comanches and Kiowas and a 4.3-million-acre tract for a Cheyenne-Arapaho reservation. Both of these settlements would include the implements for farming and building houses and schools, and the land would be guaranteed as native territory...Although the document was ratified by Congress in 1868, it was never ratified by adult males of the participating tribes — and it wasn’t long before Congress was looking for ways to break the treaty. Within a year, treaty payments were withheld and General [William Tecumseh] Sherman was working to prevent all Indian hunting rights...

In the following years, lawmakers decided the reservations were too large and needed to be cut down to individual plots called ‘allotments.’ These continual attempts to renege on the 1867 Medicine Lodge Treaty came to a head in 1903 in the landmark Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock case, in which a member of the Kiowa nation filed charges against the Secretary of the Interior. The Supreme Court ruled that Congress had the right to break or rewrite treaties between the United States and Native American tribes however the lawmakers saw fit, essentially stripping the treaties of their power.’ - Shipping Info

-

Bidder is liable for shipping and handling and providing accurate information as to shipping or delivery locations and arranging for such. RR Auction is unable to combine purchases from other auctions or affiliates into one package for shipping purposes. Lots won will be shipped in a commercially reasonable time after payment in good funds for the merchandise and the shipping fees are received or credit extended, except when third-party shipment occurs. Bidder agrees that service and handling charges related to shipping items which are not pre-paid may be charged to a credit card on file with RR Auction. Successful international Bidders shall provide written shipping instructions, including specified Customs declarations, to RR Auction for any lots to be delivered outside of the United States. NOTE: Declaration value shall be the item’(s) hammer price and RR Auction shall use the correct harmonized code for the lot. Domestic Bidders on lots designated for third-party shipment must designate the common carrier, accept risk of loss, and prepay shipping costs.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB