Martin Luther King, Jr. Letter: "As a Negro I have special concern with the influence that Soviet theory and practice have had upon the millions of co

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $5 |

| $50 | $10 |

| $200 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

About Auction

Sep 23, 2023

RR Auction support@rrauction.com

- Lot Description

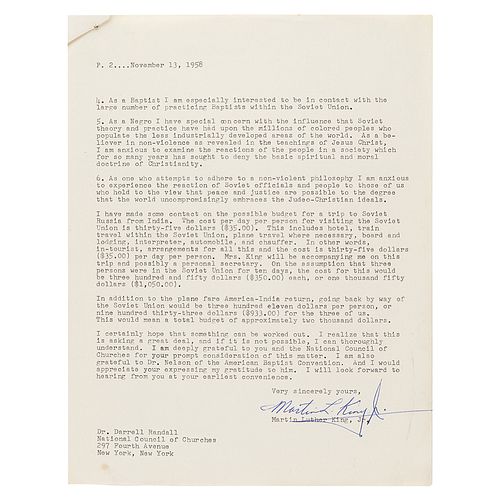

TLS signed “Martin L. King, Jr.,” two pages, 8.5 x 11, personal letterhead, November 13, 1958. Letter to Dr. Darrell Randall of the National Council of Churches in New York, in full: “Thanks for your very kind letter of recent date concerning my interest in going to Russia incident to my visit to India. First, I must apologize for being somewhat tardy in my reply. Unfortunately, your letter was misplaced during my secretary's daily trips between the office and my residence where I am convalescing. Althought [sic] we have not been able to find the letter yet, I think I am sufficiently familiar with the contents to venture a reply.

As I remember, you mentioned that Dr. Nelson of the American Baptist Convention had expressed great interest in this trip, and also the possibility of providing some funds to meet the budget. Naturally, I was very happy to know this. My reasons for desiring to go to the Soviet Union may be stated as follows:

1. Manifold international policies emerge from a limited number of important world centers. Events taking place in the United States, Russia, and India affect the life of every person on this earth. Increasingly, religious leaders, scientists, scholars, and statesmen have come to see that firsthand investigation in these important centers is an integral part of their ability to exercise their leadership responsibilities.

2. In the coming period when travel to the Soviet Union is more usual, I believe the American people will expect committed leaders to get information by serious personal inquiry rather than to rely upon secondary sources. The people will tend to respect conclusions which are based on observations and direct examination. According to my ability, I wish to be able to interpret to our people the deeper and more obscure currents of thought which dominate other peoples as well as the assumptions on which their social institutions are constructed. To do this it is necessary that personal contact be established so that both the good and the destructive elements and trends can be illustrated, analyzed and understood.

3. Among some of the more specific lines of inquiry I wish to pursue are those which would illuminate the reasons for the continued existence of religious conviction among millions of Soviet citizens, all of whom have been subjected to varying degrees of oppression and discouragement by powerful agencies of propaganda and anti-religious education. This tenacity to spiritual commitment is worthy of careful study for these precise methods to the control of man's relationship to God may be unique in human experience.

4. As a Baptist I am especially interested to be in contact with the large number of practicing Baptists within the Soviet Union.

5. As a Negro I have special concern with the influence that Soviet theory and practice have had upon the millions of colored peoples who populate the less industrially developed areas of the world. As a believer in non-violence as revealed in the teachings of Jesus Christ, I am anxious to examine the reactions of the people in a society which for so many years has sought to deny the basic spiritual and moral doctrine of Christianity.

6. As one who attempts to adhere to a non-violent philosophy I am anxious to experience the reaction of Soviet officials and people to those of us who hold to the view that peace and justice are possible to the degree that the world uncompromisingly embraces the Judeo-Christian ideals.

I have made some contact on the possible budget for a trip to Soviet Russia from India. The cost per day per person for visiting the Soviet Union is thirty-five dollars ($35.00). This includes hotel, train travel within the Soviet Union, plane travel where necessary, board and lodging, interpreter, automobile, and chauffer [sic]. In other words, in-tourist, arrangements for all this and the cost is thirty-five dollars ($35.00) per day per person. Mrs. King will be accompanying me on this trip and possibly a personal secretary. On the assumption that three persons were in the Soviet Union for ten days, the cost for this would be three hundred and fifty dollars ($350.00) each, or one thousand fifty dollars ($1,050.00).

In addition to the plane fare America-India return, going back by way of the Soviet Union would be three hundred eleven dollars per person, or nine hundred thirty-three dollars ($933.00) for the three of us. This would mean a total budget of approximately two thousand dollars.

I certainly hope that something can be worked out. I realize that this is asking a great deal, and if it is not possible, I can thoroughly understand. I am deeply grateful to you and the National Council of Churches for your prompt consideration of this matter. I am also grateful to Dr. Nelson of the American Baptist Convention. And I would appreciate your expressing my gratitude to him. I will look forward to hearing from you at your earliest convenience.” In fine condition, with a few small stains on the first page.

King’s mention of his continued convalescence relates to when Izola Ware Curry, a 42-year-old mentally disturbed woman, stabbed him at Blumstein’s Department Store in Harlem while he was signing copies of his book, Stride Toward Freedom, on September 20, 1958. Curry approached King with a seven-inch steel letter opener and drove the blade into the upper left side of his chest. King was rushed to Harlem Hospital, where he underwent more than two hours of surgery to repair the wound. Doctors operating on the 29-year-old civil rights leader said: ‘Had Dr. King sneezed or coughed, the weapon would have penetrated the aorta.‰Û_ He was just a sneeze away from death.’

Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. never did visit the Soviet Union, but on February 3, 1959, King, his wife Coretta Scott King, and his colleague Lawrence Reddick of the Montgomery Improvement Association departed for a five-week tour in India, eventually arriving in New Delhi’s Palam Airport on February 10th. During his visit, King met with Indian leaders such as Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi's widow, Kasturba Gandhi. The trip to India was primarily a pilgrimage to study Mahatma Gandhi's philosophy of nonviolence and to gain a deeper understanding of his methods of peaceful protest. King was inspired by Gandhi's principles of nonviolent resistance, and he saw the trip as an opportunity to learn from the Indian independence movement and apply those lessons to the civil rights struggle in the United States. In a radio address made during his final evening in India, King reflected: ‘Since being in India, I am more convinced than ever before that the method of nonviolent resistance is the most potent weapon available to oppressed people in their struggle for justice and human dignity. In a real sense, Mahatma Gandhi embodied in his life certain universal principles that are inherent in the moral structure of the universe, and these principles are as inescapable as the law of gravitation.’

In regard to King and the Soviet Union, the former’s seemingly soft stance on Communism placed him on unsteady ground with both the KGB and his own country’s political authority. As King rose to prominence he frequently had to defend himself against allegations of being a Communist, though his view that ‘Communism and Christianity are fundamentally incompatible’ never wavered. Although sympathetic to communism’s core concern with social justice, King complained that with its ‘cold atheism wrapped in the garments of materialism, communism provides no place for God or Christ.’ In his 1958 memoir Stride Toward Freedom, King asserted that although he rejected communism’s central tenets, he was sympathetic to Marx’s critique of capitalism, finding the ‘gulf between superfluous wealth and abject poverty’ that existed in the United States morally wrong.

Such comments by King emerged in the 1950s at the near height of U.S. tensions with the Soviets, who aimed to diminish American democracy by spotlighting the nation’s struggles with racial discrimination. As a result, the civil rights crusade became a national security imperative due to claims that the movement was subversively infiltrated by Communists. Because of this, both the Kennedy Administration and J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI authorized wiretaps of MLK and his team. Their findings, unsurprisingly, were fruitless, as were the parallel attempts of the Soviet Government.

After the Second World War, the Soviet Union sought to exploit the poor treatment of African-Americans in the United States as evidence of a worldwide struggle against American imperialism. However, to the dismay of the KGB, King repeatedly linked the aims of the civil rights movement to the fulfillment of the American dream and ‘the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence.’ In response, the KGB resolved to discredit King as a tool of American capitalism, planting articles in Africa that portrayed him as a paid pawn of the Johnson Administration. Like the American wiretaps, the Soviet campaign to discredit King proved entirely ineffective. - Shipping Info

-

Bidder is liable for shipping and handling and providing accurate information as to shipping or delivery locations and arranging for such. RR Auction is unable to combine purchases from other auctions or affiliates into one package for shipping purposes. Lots won will be shipped in a commercially reasonable time after payment in good funds for the merchandise and the shipping fees are received or credit extended, except when third-party shipment occurs. Bidder agrees that service and handling charges related to shipping items which are not pre-paid may be charged to a credit card on file with RR Auction. Successful international Bidders shall provide written shipping instructions, including specified Customs declarations, to RR Auction for any lots to be delivered outside of the United States. NOTE: Declaration value shall be the item’(s) hammer price and RR Auction shall use the correct harmonized code for the lot. Domestic Bidders on lots designated for third-party shipment must designate the common carrier, accept risk of loss, and prepay shipping costs.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB