Manhattan Project: Copper Plutonium Core Tamper Prototypes with "Fat Man" and "Little Boy" Correspondence (1944-45)

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $5 |

| $50 | $10 |

| $200 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

About Auction

Sep 23, 2023

RR Auction support@rrauction.com

- Lot Description

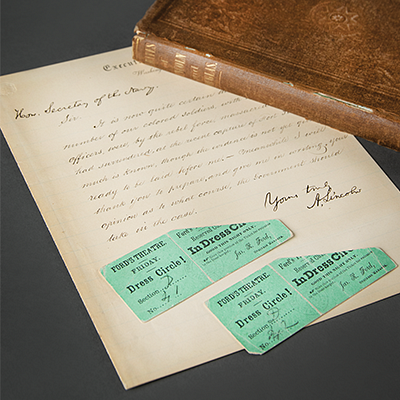

Remarkable collection of three copper tamper prototypes or test models created by the G. E. Nelson Company of Holly, Michigan, as part of secretive Manhattan Project efforts to develop the atomic bomb during World War II. Ultimately, 'Fat Man' used this style of spherical tamper to surround its plutonium core, but it was made of depleted uranium rather than copper. The heavy tamper is designed to reflect neutrons back into the central 'plutonium pit,' accelerating the nuclear chain reaction and restraining the explosion for a few crucial moments, thereby increasing the efficiency of the blast.

The three tampers, each split into two halves with ridged edges to fit together, measure as follows: 6″ outer diameter with a 5/8″ wall, weighing approximately 18.3 lbs; 3″ outer diameter with a 3/8″ wall, weighing 2.4 lbs; and 1.5″ diameter with a 3/16″ wall, weighing 0.3 lbs. Includes Nelson's circa 1944 original rough pencil sketches of cross-sections of 5″ and 6″ half-spheres, used in developing quotes for their production. These production prototypes never left the possession of G. E. Nelson and were not the subjects of radioactive experiments.

Similar hemispheric reflector shells—made from beryllium—are also known for their role in the infamous 'Demon Core' criticality accidents at Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory in 1945 and 1946. It is known that spherical copper reflectors of various sizes were the subjects of testing and criticality studies at Los Alamos during the era (see: 'Critical Masses Of Oralloy In Thin Reflectors,' LA-2203, January 1958). Based on the accompanying correspondence, it is most likely that these three sets of copper reflectors were affiliated with the G. E. Nelson Company's work on 'Fat Man' components, and/or associated nuclear weapons experiments conducted at Los Alamos. The documents also contain G. E. Nelson's bid for structural components for a "Little Boy Drop Dummy"; however, these copper tampers could not be affiliated with 'Little Boy' as it used a cylindrical mechanism, not a spherical one.

Secrecy and security were of paramount importance to the Manhattan Project. According to Nelson family legend, when the G. E. Nelson Company began building these spheres, trenchcoat-wearing agents came to inspect the facility, the government paid to have it fenced in, and a 24-hour security detail was instituted. These security concerns are evidenced in included documents from October 1944, which required a questionnaire to be submitted in order to "meet National Security requirements," involving inquiries about the citizenship of corporate officers and the employment of organized labor. Further letters from the University of Michigan, dating to October 1945, announce that four individuals no longer work for the engineering research department and should "not be permitted to have access to any work performed in your plant‰Û_nor to any papers pertaining thereto." A separate notice indicates that identification cards for two of those former employees had been lost—perhaps the reason for their dismissal—and requests that the office be notified if they are presented at the Nelson facility.

The military-industrial complex found a haven in the greater Detroit region in the early 1940s: with a large population of skilled machinists and metalworkers supporting the automotive industry, and brilliant minds in physics and engineering at the University of Michigan, the United States government relied on Michigan's ingenuity early on in the war effort. As early as October 1940, the G. E. Nelson Company—which had pioneered an innovative 'metal spinning' process—was producing steel torpedo noses, artillery shell points, battleship motor housings, and other parts for the United States Navy. It is therefore no surprise that, having proven itself as a secure and reliable government contractor, G. E. Nelson was approached in 1944-45 with requests for parts from U.S. Army Manhattan Project engineers working out of the University of Michigan's Department of Engineering Research. It is no coincidence that the University of Michigan would go on to establish the first American degree program in nuclear engineering in 1952.

Included are two of these requests for bids, marked as "Priority No. AA-1" [Top Priority]: one from October 10, 1944, signed by Lt. Robert W. Lockridge, a Manhattan Project Ordnance Division procurement leader, for parts for "Drawing No's D-1418"—designating a "Little Boy Drop Dummy," per a separate document—with Nelson quoting a grand total of $91,200 for various assemblies with and without parachute fins; and one from January 22, 1945, signed by Major F. E. Smith, with a quote for 60 "6″ O.D. x .652 Wall Copper Sphere" [matching the size of the largest copper sphere included in the lot] to be completed by February 25, 1945, at a cost of $6,600. An earlier piece of correspondence from Smith, dated October 20, 1944, declines a bid for "Spheres, necessary tools, and crating" due to a change in plans.

The most important document, however, uses the code names of the bombs—"Fat Man" and "Little Boy"—in its text, proving G. E. Nelson's involvement in their development and manufacture: a typed letter on G. E. Nelson Company letterhead, dated April 19, 1945, documenting the delivery of drawings for a "Shell Nose," "Fat Man Dummy," "Little Boy Drop Dummy Design 2A," and "Mounting Ring." Drop tests of 'Fat Man' and 'Little Boy' dummy bombs had been ongoing for about a year, allowing study and refinement of their ballistic properties: tail structures were modified to prevent wobbling and flight inaccuracies, and various bomb bay hoists, braces, and release assemblies were redesigned to better handle the five-ton weapons. It may be that the "Mounting Rings" supplied by G. E. Nelson related to these modifications. Three months later, on July 16, 1945, a plutonium implosion device of the 'Fat Man' design was tested at the 'Trinity' site in New Mexico—the first-ever detonation of a nuclear weapon. This was the ultimate proof-of-concept of the power of the atom bomb—witnessing the radiance of the blast and ensuing mushroom cloud, the famous quote from the Bhagavad Gita ran through J. Robert Oppenheimer's mind: 'Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.' On August 9th, 'Fat Man' detonated over Nagasaki, ending World War II. - Shipping Info

-

Bidder is liable for shipping and handling and providing accurate information as to shipping or delivery locations and arranging for such. RR Auction is unable to combine purchases from other auctions or affiliates into one package for shipping purposes. Lots won will be shipped in a commercially reasonable time after payment in good funds for the merchandise and the shipping fees are received or credit extended, except when third-party shipment occurs. Bidder agrees that service and handling charges related to shipping items which are not pre-paid may be charged to a credit card on file with RR Auction. Successful international Bidders shall provide written shipping instructions, including specified Customs declarations, to RR Auction for any lots to be delivered outside of the United States. NOTE: Declaration value shall be the item’(s) hammer price and RR Auction shall use the correct harmonized code for the lot. Domestic Bidders on lots designated for third-party shipment must designate the common carrier, accept risk of loss, and prepay shipping costs.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB