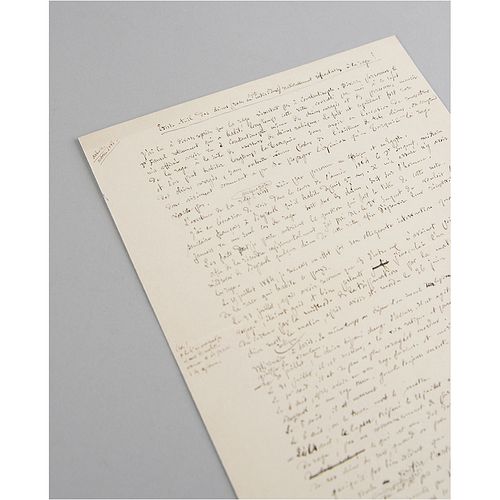

Louis Pasteur Handwritten Manuscript on Rabies Experiments with Dogs

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $5 |

| $50 | $10 |

| $200 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

About Auction

Sep 23, 2023

RR Auction support@rrauction.com

- Lot Description

Significant handwritten manuscript in French by Louis Pasteur, unsigned, one page both sides, 6.25 x 8.25, Arbois, October 1884. Remarkable manuscript penned during his rabies research, dating to eight months before the first successful human vaccination. Headed, "Do dogs exist (as a race or individually) that are naturally immune to rabies?," the manuscript reads (translated): "I have often read that rabies does not exist in Constantinople. However, several people I have consulted, most notably Dr. Fauvel, who have lived there for a long time, confirmed to me that they have definitely seen rabid dogs and people with rabies who have been bitten by those dogs in Constantinople. Although it is very rare, you can live a long time in Turkey without ever having seen a rabid dog or even heard of its existence.

It is understandable how the rumor was spread that rabid dogs do not exist. Nobody denies the existence of rabies in either Africa or Egypt. In 1884, I had the opportunity to meet Dr. Sergent, a French public health doctor who has been living in Beirut for the past 27 years. He assured me that he had never seen a single case of rabies, either in dogs or in humans. These facts force me to ask the question which is the subject of this note. To resolve these queries experimentally, I asked Doctor Sergent to kindly send me some dogs from Beirut so that I could once and for all prove their immunity against rabies.

On July 19, 1884, I received four dogs native to Beirut that Dr. Sergent generously sent me. On July 21, after having assured myself that three of them were healthy, lively and gay and had not suffered from the voyage, (Note: The 4th one was not eating and did not survive), I inoculated one of them by the method of trepanation with the medulla from the rabid dog which had died that morning after having been bitten on June 26, while in the care of Mr. Paul Simon, veterinarian in Paris. At the same time, we trepanned and inoculated a rabbit with the same brain matter from the dead dog to verify its potency.

On July 30, the dog which had been trepanned began to change its behavior. He seemed agitated. It was the ninth day after inoculation. On July 31, the dog begins to bite and has a rabies like bark. His back legs are paralyzed. On August 1, he becomes more and more enraged and is biting more. On August 4, after having been madly enraged and furiously biting with a rabid bark, the dog from Beirut demonstrates a distinctly rabid behavior, the mouth hanging open and barely barking. On August 5, he is clearly dying. On August 6, we find him dead in the morning. As of August 4, the rabbit which had been operated on by the method of trepanning on July 21, began to show that it was infected with rabies as it exhibited the beginning of paralysis. It was 14 days after being inoculated, which is the typical amount of incubation time for rabies in street dogs, when rabbits are infected by dogs.

Although it was obvious that the dog from Beirut died of rabies, we wanted to verify the existence of the disease by transmitting it to rabbits; inoculated by trepanning, the rabbits manifest a rabid paralysis after 16-18 days of incubation. Other healthy rabbits, inoculated by trepanation from the first one that died, suffered from rabid paralysis, one of them after 10 days and the other after 18 days of incubation. To summarize, the dogs from Beirut responded in the exact same manner as the dogs from France.

If rabies has never been observed in Beirut by Dr. Sergent, and if it does not seem to exist in Syria, it is because no one has ever brought it there. The dogs of these countries are ostensibly as susceptible as ours. So, our answer to the initial question we asked is NO. We have here a strong argument in favor of the opinion that rabies is never spontaneous.

Finally, I must say that it was easy to immunize the two dogs who arrived from Beirut by preventive inoculations with the virus from the one to which I had transmitted rabies. These two dogs which were immunized can tolerate today as many consecutive injections of the rabies virus as we want without the slightest effect." In fine condition.

Having witnessed a horrifying outbreak of rabies in his youth, Pasteur dedicated much of the 1880s to developing a vaccine for the deadly disease. Little was known of the disease into the 1870s: it was still widely thought that it arose spontaneously out of anger or agitation. It was also accepted as common knowledge that rabies did not exist the East, where dogs were free to roam the street: ''Constantinople and Africa are rabies-free' was the oft repeated refrain, and Eastern freedom was contrasted with Western repression, with Paris, where rabies found its refuge,' ('La Rage and the Bourgeoisie: The Cultural Context of Rabies in the French Nineteenth Century' by Kathleen Kete).

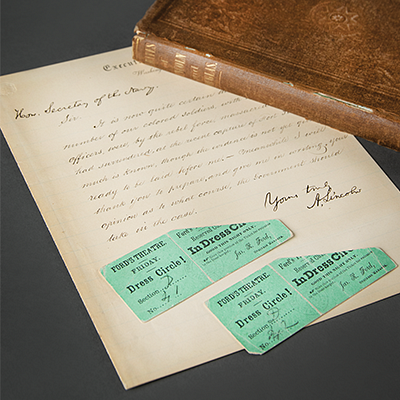

This significant manuscript outlines Pasteur's efforts to disprove the theory of 'spontaneous rabies,' as well as the idea that dogs in the Middle East were naturally immune—the experiments outlined here offered proof that the dogs had just not yet been exposed to rabies, not that they held a natural immunity. After five years of extensive study of the rabies virus and the successful treatment of several infected dogs, Louis Pasteur faced his first human patient in July of 1885. Certain that the severely bitten nine-year-old Joseph Meister would not survive without treatment, he began the course of the 13 injections; after administering all 13, one each day, in progressively stronger doses, Meister regained strength and never developed rabies. After a second successful treatment on a bitten shepherd which began in October, word spread and people began to seek him out for the vaccinations. An important scientific manuscript from the pioneering French chemist and microbiologist. - Shipping Info

-

Bidder is liable for shipping and handling and providing accurate information as to shipping or delivery locations and arranging for such. RR Auction is unable to combine purchases from other auctions or affiliates into one package for shipping purposes. Lots won will be shipped in a commercially reasonable time after payment in good funds for the merchandise and the shipping fees are received or credit extended, except when third-party shipment occurs. Bidder agrees that service and handling charges related to shipping items which are not pre-paid may be charged to a credit card on file with RR Auction. Successful international Bidders shall provide written shipping instructions, including specified Customs declarations, to RR Auction for any lots to be delivered outside of the United States. NOTE: Declaration value shall be the item’(s) hammer price and RR Auction shall use the correct harmonized code for the lot. Domestic Bidders on lots designated for third-party shipment must designate the common carrier, accept risk of loss, and prepay shipping costs.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB