John Wilkes Booth Autograph Letter Signed (1860) Written the Month of President Lincoln's Election

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $5 |

| $50 | $10 |

| $200 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

About Auction

Sep 23, 2023

RR Auction support@rrauction.com

- Lot Description

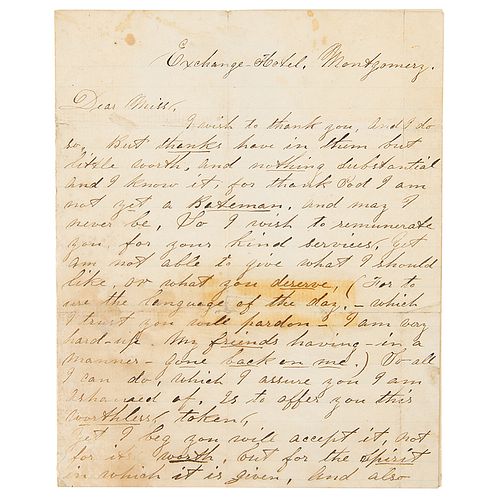

Exceedingly rare ALS signed “J. Wilkes Booth,” two pages on two adjoining sheets, 6.5 x 8, no date [November 1860]. Addressed from the Exchange Hotel in Montgomery, Alabama, a handwritten letter to an unidentified young woman, in full: “I wish to thank you, And I do so, But thanks have in them but little worth, and nothing substantial and I know it; for thank God I am not yet a Bateman, and may I never be, So I wish to remunerate you for your kind services. Yet am not able to give what I should like, or what you deserve, (For to use the language of the day, — which I trust you will pardon — I am very hard-up. My friends having — in a manner — Gone back on me.) So all I can do, which I assure you I am ashamed of, is to offer you this worthless token. Yet, I beg you will accept it, not for its worth, but for the Spirit in which it is given. And also keep it. That it may remind you I am still your debtor.” Expertly and indiscernibly strengthened and repaired to near fine condition, with staining to the first page, and restoration of substantial paper loss to the second page, none of which adversely affects readability or the boldness of the handwriting. Overall, a fine example of the darkly and clearly penned handwriting and signature of John Wilkes Booth, who remains rare across all formats.

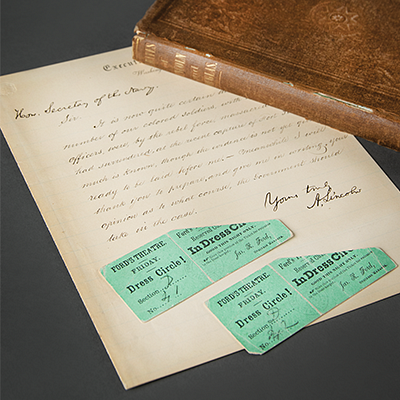

Accompanied by two letters from pioneer autograph dealer Mary A. Benjamin that she sent to Dr. John K. Lattimer, to whom she sold this letter in 1973.

Provenance: Walter Benjamin Autographs (1973); Heritage Auctions (2008); University Archives (2009)

Portions of this letter were published on page 93 in Terry Alford’s book Fortune’s Fool: The Life of John Wilkes, which relates to his time in Montgomery and his lead role in Romeo and Juliet. In part: ‘The evening came off well, declared the Mail in its notice of the following day. Its reviews of Booth continued mixed, however, in the vein of ‘Mr. Wilkes showed that he can learn to play Romeo with great power, though as yet his conception is crude.’ Kate [Reignolds] was positive about her costar, saying that ‘he was really a beautiful creature — you couldn't help admiring him — so amiable, so sweet, so sympathetic.’ Papa Bateman grew interested in him. A man of quick insight, Bateman boasted that he only required five minutes to know the measure of a man, and in Booth he saw something special. Booth was ‘so good in the part that Mr. Bateman had serious thoughts of engaging him for the jeune premier character and bringing him to England to act with Miss Bateman.’ Booth never went to England or acted again with Kate. ‘Some trifle interrupted this engagement,’ recalled a journalist. ‘This purpose, if it had been carried out, would have saved a great actor to the stage and possibly changed the political destiny of a nation.’ Booth seemed relieved to have escaped Papa's clutches, writing a friend, ‘Thank God, I am not yet a Bateman, and may I never be.’

‘Booth's social life was active in Montgomery, bearing out the validity of Lewis's observation of the Deep South that ‘the people in that section uniformly treated actors with a sense of both their social and professional worth.’ The affable and romantic young actor was besieged by the attention of the citizens. The odds and ends that constitute Booth's effects, found after his death, include an invitation to attend the anniversary dinner of the St. Andrew's Society of Montgomery on November 30, 1860. It is unknown if he went, but this stray piece of paper is evidence of the welcome of which Booth was deemed worthy. His problem was not a shortage of such invitations. Rather, like countless other young people with places to go and things to do, he had no money. ‘I am very hard up,’ he complained to a friend.’

H. L. Bateman (1812-1875) was a former actor who managed a theatre in St. Louis in 1855 and moved to New York City in 1859. He managed his two daughters across the country in theatrical productions of plays written by, among others, his wife. In New York, Bateman began managing other actors. Booth had no desire to work for Bateman.

Although undated, Booth undoubtedly wrote this letter in November 1860, the month Lincoln was elected President. William Warren Rogers, Jr., from his book ‘Confederate Home Front: Montgomery During the Civil War,’ notes that ‘No event was more keenly anticipated than the opening of the Montgomery Theater. Over the spring and summer, the vaguely Italianate brick structure rose steadily at the corner of Perry and Monroe Streets. On October 14 [1860], opening night, an audience of over 400 enjoyed 'The School for Scandal,' Richard Brinsley Sheridan's comedy of manners‰Û_Late in the year, when John Wilkes Booth appeared, the 'Post' described him as a 'young and promising tragedian.’” The Exchange Hotel, from which Booth wrote this letter, was on the northwest corner of Commerce and Montgomery Streets, two blocks from the Montgomery Theatre.

From ‘Consider the Elephant,’ a historical novel by Aram Schefrin, the story of Booth’s life and death as told by his brother, Edwin: ‘Wilkes took the stage in Montgomery on the first day of November, in the role of Duke Pescara, one of Papa's favorites. The city was in chaos over the coming Presidential election, yet Wilkes soon had the same adoring crowds he'd come to expect in Richmond, and the ladies were very kindly disposed, and disposed of, one by one.’ This letter appears to be written to one of those ladies. Booth's last acting appearance was on March 18, 1865, at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C., once again in the role of Duke Pescara in ‘The Apostate.’ Four weeks later, he returned to Ford's Theatre and assassinated President Abraham Lincoln.

In ‘The Life, Crime and Capture of John Wilkes Booth,’ George Alfred Townsend writes of an incident involving one of Booth's lady friends, which he believes occurred in Montgomery. In part, ‘In Montgomery, if I do not mistake, Booth met the woman from whom he received a stab which he carried all the rest of his days. She was an actress, and he visited her. They assumed a relation creditable only in 'La Boheme,' and were as tender as love without esteem can ever be. But, after a time, Booth wearied of her and offered to say good by. She refused - he treated her coldly; she pleaded - he passed her by. Then, with a jealous woman's frenzy, she drew a knife upon him and stabbed him in the neck, with the intent to kill him. Being muscular, he quickly disarmed her, though he afterward suffered from the wound poignantly.’

John Wilkes Booth was booked at the Montgomery Theatre for three weeks. By its content, this letter seems to have been penned as he prepared to depart. Leaving the city that became the first capital of the Confederacy two months later, he traveled 350 miles east to Savannah, Georgia, and took the steamship Huntsville north to New York, never to return to Montgomery. - Shipping Info

-

Bidder is liable for shipping and handling and providing accurate information as to shipping or delivery locations and arranging for such. RR Auction is unable to combine purchases from other auctions or affiliates into one package for shipping purposes. Lots won will be shipped in a commercially reasonable time after payment in good funds for the merchandise and the shipping fees are received or credit extended, except when third-party shipment occurs. Bidder agrees that service and handling charges related to shipping items which are not pre-paid may be charged to a credit card on file with RR Auction. Successful international Bidders shall provide written shipping instructions, including specified Customs declarations, to RR Auction for any lots to be delivered outside of the United States. NOTE: Declaration value shall be the item’(s) hammer price and RR Auction shall use the correct harmonized code for the lot. Domestic Bidders on lots designated for third-party shipment must designate the common carrier, accept risk of loss, and prepay shipping costs.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB