John Steinbeck Archive with Incredible Handwritten Letter on Writing

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $5 |

| $50 | $10 |

| $200 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

About Auction

Mar 8, 2023

RR Auction support@rrauction.com

- Lot Description

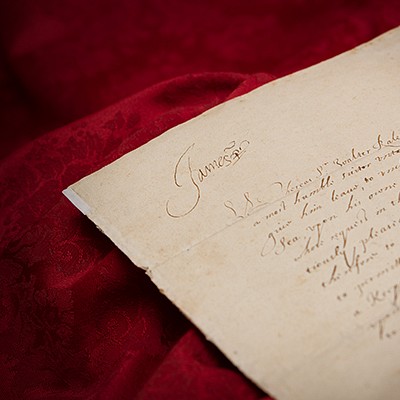

Unique archive of correspondence from Nobel Prize-winning novelist John Steinbeck, evidently to his literary agent, Elizabeth Otis, including a 12-page unsigned handwritten letter in pencil, two TLSs, and five unsigned typescript copies of his letters to her.

Most significant is the handwritten letter, dated "June 24, I think," no year [1966?], in which he eloquently discusses the mindset and duties of a writer, and comments on his work regarding Arthurian legend. The subject work, The Acts of King Arthur and His Noble Knights, would be published posthumously in 1976. The unsigned letter, in small part: "A writer is essentially a very talkative person who has not the power of speech. And so he takes out his impulses with a pencil. The only social advantage he has over other bores lies In the fact that no one has to read him, no one that is except his agent. Relatives can avoid it, friends do. I am convinced that the function of critics is to try to persuade writers not to write. Out of their failure in this direction they have bitten out a career, which often consists in not reading what they set out to destroy‰Û_

For writers do not write for themselves. They write for someone to read and they will take anyone. I sometimes read beautiful paragraphs to Angel the Dog. The balance and flow and rhythm of writing is to my mind an exercise of dexterities so long practiced that they have become reflexes. But as with the fine reflexes of tennis or boxing, the dexterities must be kept alive by use. They become uncertain and clumsy through a lack of use. And sometimes it is well to use the letter as a bull pen for warming up the pitcher.

I believe that every book is written to someone. The addressee may be a spirit, a presence, a demivierge, a child born too late to talk to or a parent who died or went away too soon, a lover with whom rings but not empathies were exchanged. But all of these targets for writing have common quality. They represent a lack, a hunger or a failure. They are the muses to be invited and flattered and propitiated. Writing is such an exposed and lonely state that one must have an associate even if he has to be invented. Perhaps 'familiar' in the witchcraft sense would be the better word, yes, familiar.

It is possible that a short story might be a piece of observed external reality, but a book is the writer's self, far more penetrating than he himself knows. Everything he is and knows goes into it. He may try to conceal himself, but it never works, all of his devices and subterfuges and dodges show up in a book. And it goes much further than that. The book becomes an entity, a kind of extra-personal person. And it may well, and often does take a direction not at all intended by the writer. A great short story seems to be shot in from the stars, but a great book grows out of the earth, wherefore we witness, sometimes with amazement a short story, but a book is ourselves. No psychiatrist can draw from a patient the depth and content that resides in a book.

Often a writer is rocked with amazement to see what has come out of him. It is a great mystery and anyone who approaches it flippantly commits a crime against some imperishable force to which humans have vague and fumbling access.

For myself, after the years of planning and scheming and practicing, I approach a coming book as though it were a temple in which the god had taken true residence. After all the years I have served this altar, I still approach it with awe, and with a kind of joyful terror.

Elizabeth, the Arthur book was always meant to be Sir Mary's book, and I put it off and hesitated and then she went away. For a time I considered that it was over; that now it could not happen. But a book, if it is truly meant, is a great and overwhelming force that cannot be denied. What I think about reasons may not be true reasons, but only excuses. For see: Mary is still about, changing from day to day but still present. I know that she will fade, grow dimmer and less real until she merges with the ocean of the dead. Even now she is probably not the Sir Mary who once lived. And her book? Well, maybe it is better that it welted, and believe me, it waited, not I. Sir Mary was a cantankerous curmudgeon, didactic, and the more positive as she was the less sure." He goes on to fondly recall his sister Mary, who passed away in 1965, with some commentary on stories and memory.

He continues to comment on the Arthur project: "I think my wish to reword Arthur is valid. For myself I love the look and sound and feel of middle English. I take great joy in the glorious words no longer in usage, but my feeling about the Morte of Caxton and perhaps Malory, is far from universal. I have seen people stop reading rather than to look up an old and lovely word now lost to us. I don't want to translate these stories into modern English which in a short time may be as dated and obsolete to a future reader as middle English is to most of us. To the best of whatever ability and understanding I have, I would wish to find a timeless English, simple and permanent but retaining, if that is possible, the noble flow and rhythms of Malory‰Û_The matter of Arthur induces a thousand whys—and among the first is why is the Arthurian cycle so permanently and universally popular? It is not language. There are many thousands of passionate Arthurians in Japan who have only read the Morte in Japanese. Arthur and his knights have been known and loved in Germany, in Italy, in France, in Sicily since the early Middle Ages."

Speaking to the universal nature of enduring literary works, he goes on: "Our species has stories as its has fingers. They are permanent and unchanging, and whether they are entabletured in the Iliad, the Old Testament, the Morte d'Arthur or Huckleberry Finn, all of them have one thing in common, they may be told against any kind of foreign or exotic or ancient background, the costumes, weaponry, the social procedures, which we call manners may be strange, even incomprehensible to us but the dramatis personae, the people must be ourselves. We must recognize our failure and our fears, our courage and our dishonesties, our bursting and flowering energy and our black and smothering despairs. Only if the story is so peopled, is it permanent. We may be as heroic as Achilles and as steadfast as Hector, but only when Achilles sulks in his tent out of pique, only when Hector's guts turn to water in fear so that he turns and flees, do we accept and treasure perhaps because we recognize ourselves good and bad. Of the all good or all bad we are skeptical‰Û_Of course we admire goodness and we respect greatness, but it is our frailties which relate us. I think perhaps in our secret holy of the mind we are deeply aware of our faults and suspicious of our virtues. And perhaps the universality of our insecurity makes us flock to our brothers in imperfection." Steinbeck carries on at length in a similar manner.

The first TLS is signed in pencil, "John," two pages, 8.5 x 11, no date but circa December 1957. Steinbeck comments on an enjoyable Christmas party before candidly turning to the health of his wife: "Maybe Elaine can talk to you now. If she doesn't talk to some one pretty soon I am afraid for her. She has used up just about all the bravery ten people draw on in their life times. I'm going to suggest that she call you tomorrow, but I don't know whether she will or not. I don't think she needs psychiatric help. I just think she needs help. I am doing everything I can and lord how I love her. But she is driven into a corner and there doesn't seem to be any exit." He mentions some business matters, including the purchase of a new typewriter ("The type face is so beautiful that I may even learn to be more careful just because one would hate not to use such beautiful type correctly and nicely") and his current reading, Robert Graves: "I've been reading Graves new translation of Suetonius‰Û_maybe it isn't a bad one. He is a little less careful than Tacitus and lacks the grandeur of Herodotus and the niceness of Thucidides but he's pretty good just the same. He has order and precision. And Graves has made a very fine translation."

The second TLS is signed "with love, John," one page, 8.5 x 11, personal letterhead, December 1958. Steinbeck comments on his family history in the Holy Land—his great-grandfather and grandfather both spent time there—and the latter had recovered wood from a lightning-struck ancient olive tree. He notes: "In our family it has been customary for us to make little crosses of this wood for our children and for certain few others. I still have a few fragments, as hard and brittle as coal. And so I have made this little cross for you‰Û_You will find that it takes kindly to your touch‰Û_I don't know what you think or feel about symbols or talismans, but of one thing you can be sure. If there was indeed an Agony in the Garden of Gethsemane and a Betrayal—the tree from which the cross was made was there."

In overall fine condition. Accompanied by five unsigned typescript copies of letters by Steinbeck, offering further commentary on his life and work, and lending greater insight into his relationship with Elizabeth. A remarkable literary archive with superior content from one of the great American writers of the 20th century. - Shipping Info

-

Bidder is liable for shipping and handling and providing accurate information as to shipping or delivery locations and arranging for such. RR Auction is unable to combine purchases from other auctions or affiliates into one package for shipping purposes. Lots won will be shipped in a commercially reasonable time after payment in good funds for the merchandise and the shipping fees are received or credit extended, except when third-party shipment occurs. Bidder agrees that service and handling charges related to shipping items which are not pre-paid may be charged to a credit card on file with RR Auction. Successful international Bidders shall provide written shipping instructions, including specified Customs declarations, to RR Auction for any lots to be delivered outside of the United States. NOTE: Declaration value shall be the item’(s) hammer price and RR Auction shall use the correct harmonized code for the lot. Domestic Bidders on lots designated for third-party shipment must designate the common carrier, accept risk of loss, and prepay shipping costs.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB