John Quincy Adams Autograph Letter Signed as 20-Year-Old on Newly Drafted US Constitution (1787)

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $5 |

| $50 | $10 |

| $200 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

About Auction

Sep 23, 2023

RR Auction support@rrauction.com

- Lot Description

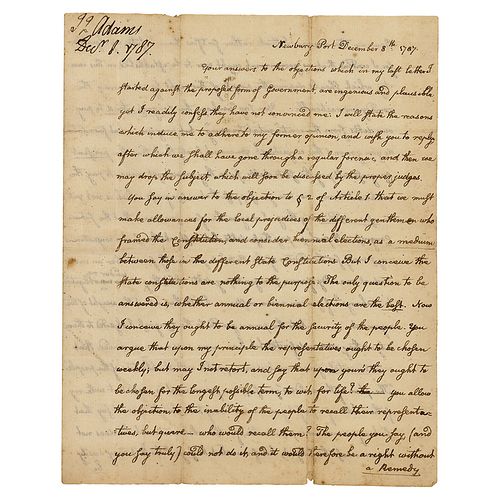

ALS signed “J. Q. Adams,” four pages on two adjoining sheets, 7.25 x 9, December 8, 1787. Handwritten letter to his first cousin, William Cranch, commenting on the recently drafted Constitution of the United States, which had been submitted to the states for ratification. In full: "Your answers to the objections which in my last letter I stated against the proposed form of Government, are ingenious and plausible yet I readily confess they have not convinced me: I will state the reasons which induce me to adhere to my former opinion, and wish you to reply after which we shall have gone through a regular forensic, and then we may drop the subject, which will soon be discussed by the proper judges.

You say in answer to the objection to §2 of Article 1, that we must make allowances for the local prejudices of the different gentlemen who framed the Constitution, and consider biennial elections, as a medium between those in the different State Constitutions. But I conceive the State Constitutions are nothing to the purpose. The only question to be answered is, whether annual or biennial elections are the best. Now I can conceive they ought to be annual for the security of the people. You argue that upon my principle the representations ought to be chosen weekly; but may I not retort, and say that upon your's they ought to be chosen for the longest possible term, to wit for life? You allow the objection, to the inability of the people to recall their representatives, but quere—who would recall them? The people you say, (and you say truly) could not do it, and it would therefore be a right without a remedy. This answer, I think rather fortifies than refutes my objection for, I contend that no government ought ever to be established, in this country, which should deprive the people of this right, by rendering the remedy impracticable. You say perhaps the Congress intend to pay our debts from the continental treasury, but pray upon what foundation do you ground this conjecture? You cannot surely think that the present Congress will pay the State debts, since they cannot get money to pay the continental one. Nor can you suppose that a Congress which is not yet in esse, intend any thing. I imagine therefore, you mean that the future Congress will perhaps pay these debts. But I ask whether such a conjecture is any security for the creditors of the States? Do you usually find either an individual or a body of men, so wager to pay debts, which they are under no obligation to discharge? If you can name instances I will then admit the weight of the argument.

As to the powers granted to the Congress I objected to them only as they were indefinite; but I am more and more convinced, that a continental government, is incompatible with the liberties of the people. 'The plan of three orders,' you say, 'in government is consistent with my father's Idea of a perfect government.' Very true, but he does not say that such a government is practicable, for the whole continent. He does not even canvass the subject, but from what he says, I think it may easily be inferred that he would think such a government fatal to our liberties. But I am far from being convinced that upon the proposed project, the three orders would exist; it appears to me, that there would in fact be no proper representation of the people, and consequently no democratical branch of the constitution. It is impossible that eight men should represent the people of this Commonwealth. They will infallibly be chosen from the aristocratic part of the community, and the dignity, as well as the power of the people must soon dwindle to nothing.

Blackstone Vol. I, p. 159 supposes it necessary that the commons should be chosen 'by minute and separate districts, wherein all the voters, are, or easily may be distinguished.' Now if this Commonwealth be divided into eight districts, each of which shall elect one person, will any of these districts be minute? I wish if you have time you would again peruse the defence of the constitutions; it appears to me, there is scarcely a page in the book, which does not contain something that is applicable against this proposed plan: see particularly the 54th Letter; one passage of which I will quote because it is very much to the purpose. 'The liberty of the people depends entirely on the constant and direct communication between them and the legislature, by means of their representatives. Now in this case, there could not possibly be any such communication, and this you yourself admit when you prove the inability of the people to recall their representatives even if the right should be given them.

You are mistaken I believe when you say the jealousy of the people is considered as an error on the right side. It is said, 'the caution of the people is much to be applauded,' and it is not usual to applaud an error, even if it be on the right side.

As to the 13th Article you ask whether it was not made by a majority of the people? If you enquire for information I can answer no. It was made by the whole people. The confederation did not take place till all the States had acceded to it; Maryland delayed the matter I think as much as two years longer than any of the other States, so that the confederation which was made in July 1778 was not ratified till March 1781, and thus upon your own argument, I say, that what was made by the whole, can with propriety be altered by the whole.

In short, I must confess I am still of opinion that if this constitution is adopted, we shall go the way of all the world: we shall in a short time slide into an aspiring aristocracy, and finally tumble into an absolute monarchy, or else split into twenty separate and distinct nations perpetually at war with one another; which God forbid!" In fine condition.

Provenance: The archive of a direct descendant of Abigail Adams's only sister, Mary Cranch. Never before offered. - Shipping Info

-

Bidder is liable for shipping and handling and providing accurate information as to shipping or delivery locations and arranging for such. RR Auction is unable to combine purchases from other auctions or affiliates into one package for shipping purposes. Lots won will be shipped in a commercially reasonable time after payment in good funds for the merchandise and the shipping fees are received or credit extended, except when third-party shipment occurs. Bidder agrees that service and handling charges related to shipping items which are not pre-paid may be charged to a credit card on file with RR Auction. Successful international Bidders shall provide written shipping instructions, including specified Customs declarations, to RR Auction for any lots to be delivered outside of the United States. NOTE: Declaration value shall be the item’(s) hammer price and RR Auction shall use the correct harmonized code for the lot. Domestic Bidders on lots designated for third-party shipment must designate the common carrier, accept risk of loss, and prepay shipping costs.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB