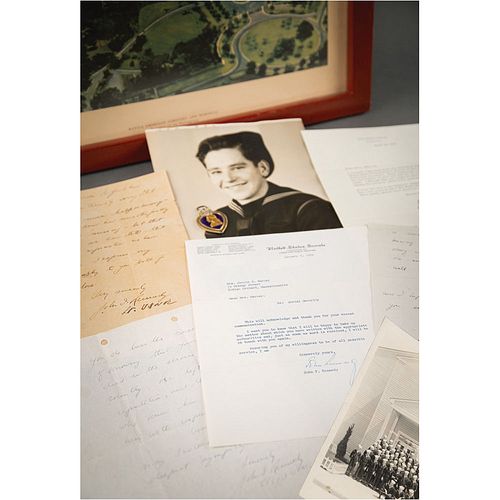

John F. Kennedy (4) Signed Letters to the Mother of Harold Marney, a Lost Crew Member of PT-109 - with a Purple Heart medal, photographs, and archival

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $5 |

| $50 | $10 |

| $200 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

About Auction

Nov 8, 2023

RR Auction's November Fine Autographs and Artifacts auction offers an extraordinary and wide-ranging selection of the rare and remarkable. RR Auction support@rrauction.com

- Lot Description

Extraordinary archive from the family of Harold W. Marney, one of two crew members killed when PT-109, a torpedo-armed fast attack vessel used by the U.S. Navy in World War II commanded by Lt. John F. Kennedy, was rammed and sunk by the Japanese destroyer Amagiri near the Solomon Islands on August 2, 1943. The archive is highlighted by four letters sent by JFK, including one as American president, to Harold Marney’s mother, Jennie, which were later preserved by her family members for over 70 years and were unknown and unpublished until Ronnie Paloger acquired it from RR Auction in 2014. In addition to these letters are Marney’s posthumously awarded Purple Heart medal, the telegram sent to the family informing them of his loss, a few photos, and various related correspondence.

This incredible archive documents 18 years of correspondence between John F. Kennedy and Harold’s mother, in spite of the fact that Kennedy had known Marney for only one week before he was killed. After reading these letters, which show the extraordinary character, compassion, empathy, and loyalty of a 26-year-old man, no one should be surprised that one day John F. Kennedy would become the president of the United States. This archive also documents a mother’s anguish over her son’s classification as “missing in action,” her denial, and finally acceptance of her son’s death.

Highlights of this correspondence include two handwritten letters that Kennedy wrote to Mrs. Marney in late September 1943 from Chelsea Naval Hospital — where Kennedy was recuperating from his back injury caused by the PT-109 collision with the Amagiri — responding to her inquiry regarding any information about her son, after receiving official notification that Harold was missing. Kennedy writes two poignant and compassionate letters to Mrs. Marney. In the first, he writes, “This letter is to offer my deepest sympathy to you for the loss of your son. I realize that there is nothing that can say [that] can make your sorrow less; particularly as I knew him; and know what a great loss he must be to you and your family. Your son rode the PT 109 with me on the night of August 1-2 when a Japanese destroyer, travelling at high speed cut us in two, as we turned into him for a shot. Harold had come aboard my boat a week before to serve as engineer. He fitted in quickly, and was very well-liked by both the officers and the men. He knew his job and he did it effectively, and with great cheerfulness—an invaluable quality out here. I am truly sorry that I cannot offer you hope that he survived that night. You do have the consolation of knowing that your son died in the service of his country. He left a fine reputation, and those of us who knew him think of him with respect and affection. Again, Mrs. Marney, may I extend to you my deepest sympathy.”

The second letter: “I received this morning your letter requesting more definite information in regard to your son Harold. I deeply regret that I cannot give you more than I have already written from the time that the destroyer hit us—nothing more was seen or heard from Harold. When the crew was finally united around the floating bow—we could find no trace of him—although every effort was made to find him. I am terribly sorry that cannot be of more help‰Û_I know how unsatisfactory is the word ‘missing’—but that is all that we can tell—that is all of the information we have. Again I express my deep sympathy to you both for your great loss.”

The third handwritten letter in response to a condolence card that Mrs. Marney sent Kennedy, after his brother Joe was killed in action flying over Germany during a secret mission on August 15, 1944. It reads: “I want you to know how much I appreciated your card. I know you know how we all feel—boys like Harold and my brother Joe can never be replaced—but there is some consolation in knowing that they were doing what they wanted to do—and were doing it well. Thank you again and I hope that I shall see you sometime again.” This letter is accompanied by a copy of Joseph P. Kennedy, Jr.’s last letter to JFK, August 10, 1944, sent two days before his fatal flight.

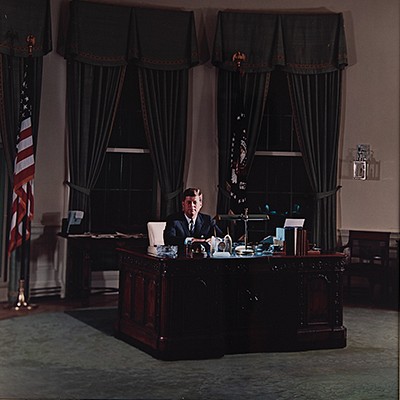

The fourth letter was typed and signed by President Kennedy on April 24, 1961, on official White House stationery, 18 years after his first letter to Mrs. Marney in 1943. President Kennedy spent the time and effort to send Mrs. Marney an original wood-framed photograph of the Manila American Cemetery and Memorial along with this letter noting her son Harold’s name on this monument. He writes: “I recently requested from the American Battle Monuments Commission a picture of the Manila American Cemetery, whose memorial wall bears the inscription of your son and my former shipmate. I thought that you might be interested in having the picture, which I am enclosing. If ever you are in the Nation’s capital, I would like very much to have the White House and other public places here shown to you.”

This archive includes three letters that Massachusetts Senator Henry Cabot Lodge wrote Mrs. Marney in response to her asking for his help in getting more information about her son, despite the letters she had already received from Kennedy telling her that her son was dead. In one of these letters Lodge responds to Mrs. Marney’s feelings of “belief that your son is not dead but is probably alive somewhere on a Japanese Island or prison.” Also included are typed letters with secretarial signatures of Senator Kennedy to Mrs. Marney in 1958 and 1959, where Kennedy interceded on her behalf for social security benefits and other issues that he tried to help her with.

Significantly, Harold Marney’s Purple Heart inscribed on the back “FOR MILITARY MERIT HAROLD W. MARNEY MOMM 2c USN,” and citation from October 16, 1944 for “MILITARY MERIT AND FOR WOUNDS RECEIVED IN ACTION resulting in his death August 2, 1943” is part of this archive.

As Dave Powers writes in his book ‘Johnny We Hardly Knew Ye,’ the PT-109 incident made John Kennedy a war hero that helped him in his first political contest in the 1946 Congressional Campaign. Powers notes that the Reader’s Digest reprint (the original is in this archive) of John Hersey’s article ‘Survival,’ about Kennedy’s heroism, was sent to every veteran on the voting list, and the whole district was blanketed with copies. Kennedy’s wartime heroism was highly effective when the vote of the veterans was to be a big factor. None of Kennedy’s opponents had a war record worth talking about and Kennedy’s well-known display of incredible courage in the South Pacific aboard the PT-109 gave him an aura of glamour that overshadowed his political inexperience. Though Kennedy supporters played up his war record during the primary campaign, Kennedy himself seldom mentioned it and squirmed uncomfortably when he was introduced at rallies as a war hero. In one particular speech, Powers remembers Kennedy talking at length about the heroism of Patrick McMahon, the 41-year-old engineer of the PT-109 who was badly burned when the torpedo boat was run down and wrecked by the Amagiri. Kennedy referred to himself only once, and only very briefly, as McMahon’s commanding officer, and never mentioned in the speech that he himself had saved McMahon’s life by swimming for five hours with a strap from the crippled engineer’s lifebelt clenched between his teeth.

In terms of content, this archive represents the pinnacle of any John F. Kennedy wartime correspondence, and the two letters describing the PT-109 incident in such detail, specifically, are arguably the two most historically significant handwritten John F. Kennedy letters ever written, and unquestionably serve as the highlights of the entire Paloger John F. Kennedy collection. - Shipping Info

-

Bidder is liable for shipping and handling and providing accurate information as to shipping or delivery locations and arranging for such. RR Auction is unable to combine purchases from other auctions or affiliates into one package for shipping purposes. Lots won will be shipped in a commercially reasonable time after payment in good funds for the merchandise and the shipping fees are received or credit extended, except when third-party shipment occurs. Bidder agrees that service and handling charges related to shipping items which are not pre-paid may be charged to a credit card on file with RR Auction. Successful international Bidders shall provide written shipping instructions, including specified Customs declarations, to RR Auction for any lots to be delivered outside of the United States. NOTE: Declaration value shall be the item’(s) hammer price and RR Auction shall use the correct harmonized code for the lot. Domestic Bidders on lots designated for third-party shipment must designate the common carrier, accept risk of loss, and prepay shipping costs.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB