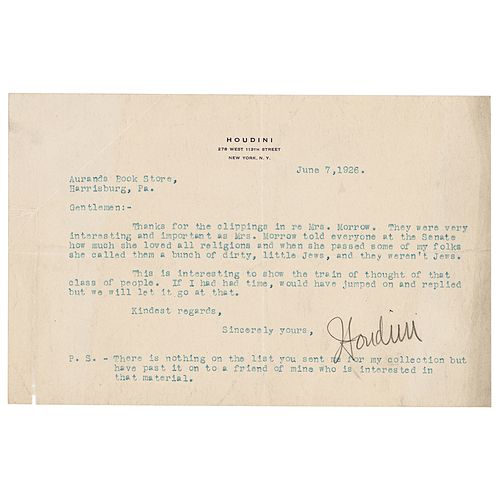

Harry Houdini Typed Letter Signed on Anti-Semitic Remarks

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $5 |

| $50 | $10 |

| $200 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

About Auction

Sep 13, 2023

RR Auction support@rrauction.com

- Lot Description

TLS signed in pencil, “Houdini,” one page, 8.5 x 5.5, personal letterhead, June 7, 1926. Letter to the Aurands Book Store in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, in full: “Thanks for the clippings in re Mrs. Morrow. They were very interesting and important as Mrs. Morrow told everyone at the Senate how much she loved all religions and when she passed some of my folks she called them a bunch of dirty, little Jews, and they weren't Jews. This is interesting to show the train of thought of that class of people. If I had had time, would have jumped on and replied but we will let it go at that.” A postscript: “There is nothing on the list you sent me for my collection but have past [sic] it on to a friend of mine who is interested in that material.” In very good to fine condition, with a crease to the upper left, and two very short edge tears.

Although the identity of “Mrs. Morrow” remains uncertain, this letter, its date, and its mention of “the Senate” points to Harry Houdini’s visit to Washington, D.C., when he testified before the Subcommittee on the Judiciary of the Committee on the District of Columbia in February and May of 1926, serving as a central witness at congressional hearings for a bill to regulate fortune telling in Washington. As a dedicated psychic investigator intent on exposing all mediums as frauds, Houdini testified before his toughest audience yet as the room was packed with local fortune tellers, astrologers, mediums, and spiritualists. Houdini’s antics enthralled some of the members of the committee, while others seemed confused or irritated. Despite his best efforts, however, the bill did not pass.

Harry Houdini was born Erich Weisz to a Jewish family, his father serving as rabbi of the Zion Reform Jewish Congregation in Appleton, Wisconsin, following their move from Hungary in 1878. Houdini never lost touch with his Jewish heritage, and in a feature story in the Milwaukee Sentinel from November 1, 1926, members of Milwaukee’s Jewish community claimed that Houdini was apparently very serious about Jewish tradition, that his friends ‘know him as a man devoutly religious, who, wherever his performance brought him, carried his tefillin, phylacteries and mezuzahs, Jewish credal symbols, with him.’

Saul J. Singer, from JewishPress.com, noted that ‘Houdini was particularly important to American Jews, for whom he came to embody the idea that a Jew could achieve success in an anti-Semitic world. For Jews who had a long history of fear and vulnerability, Houdini was the ultimate contemporary symbol of strength, and the renowned escape artist became the paradigm of the Jewish immigrant’s belief that he could escape the metaphorical shackles of Jewish history. Even after achieving great success, Houdini maintained his ties to Judaism and his loyalty to his Jewish family, saying: ‘I never was ashamed to acknowledge that I was a Jew, and I never will be.’’ - Shipping Info

-

Bidder is liable for shipping and handling and providing accurate information as to shipping or delivery locations and arranging for such. RR Auction is unable to combine purchases from other auctions or affiliates into one package for shipping purposes. Lots won will be shipped in a commercially reasonable time after payment in good funds for the merchandise and the shipping fees are received or credit extended, except when third-party shipment occurs. Bidder agrees that service and handling charges related to shipping items which are not pre-paid may be charged to a credit card on file with RR Auction. Successful international Bidders shall provide written shipping instructions, including specified Customs declarations, to RR Auction for any lots to be delivered outside of the United States. NOTE: Declaration value shall be the item’(s) hammer price and RR Auction shall use the correct harmonized code for the lot. Domestic Bidders on lots designated for third-party shipment must designate the common carrier, accept risk of loss, and prepay shipping costs.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB