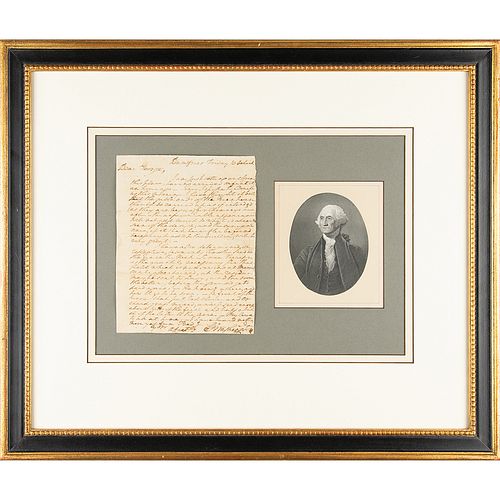

George Washington Autograph Letter Signed

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $5 |

| $50 | $10 |

| $200 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

About Auction

Aug 10, 2022

RR Auction support@rrauction.com

- Lot Description

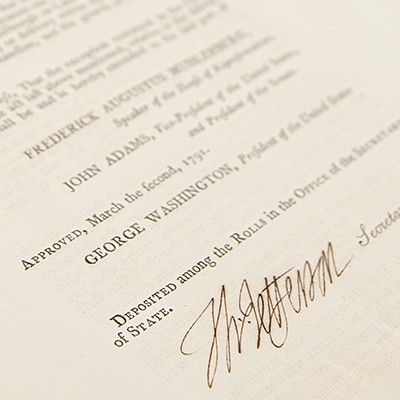

ALS as president, signed “Go: Washington,” one page, 6.75 x 8.5, April 8, 1791. Handwritten letter to his nephew George Augustine Washington, penned from Dumfries, Virginia, during his presidency. The recipient, George Augustine Washington, capably managed Mount Vernon's farms during Washington's absences in Philadelphia at the Constitutional Convention and during his presidency. Here, President Washington offers some advice on happenings on his properties, focusing on a construction project and preparations for the planting season. Most remarkably, he conveys his complete trust in one of his slaves, Davy Gray, to begin planting.

In full: "I am just setting out from this place, having arrived safe at it an hour ago. Since I spoke to Cornelias this morning I have thought it best that the gable ends of the Green house should be carried up as if intended (as they are begun) for Chimneys hereafter, the unfavourable appearance will not add much to what is already seen of the design; and the convenience, if it shall hereafter be found necessary to add to the building, will be very great.

I have also determined, on reflection, to sow only Timothy Seed on the rye in the Neck. So soon therefore as the quantity necessary for that field which is now sowing at Morris’s, can be ascertained, all the residue may be sent to Davy; and the sooner the better, before the ground gets hard again. He knows where and how it is to be sown. In front of the House I shall put Red Clover and Orchard grass mixed; and if seed enough about 10 lbs of the first and half a bushel of the latter to the Acre. My love to all at home. I have heard nothing more yet from Fred'g." Handsomely mounted, matted, and framed with a portrait to an overall size of 24 x 20. In fine condition, with trimmed edges.

Davy Gray was about sixteen years old when he first came to Mount Vernon in 1759, as part of Martha Washington’s dower share of enslaved workers from the Custis estate. The young man became a field-worker on several of Washington’s farms. As early as 1778 he was supervising other enslaved workers. By 1799 then-fifty-six-year-old Gray was overseer at Muddy Hole Farm, where he lived with his wife, Molly. At various times, Washington also assigned him to oversee the fields of River and Dogue Run Farms.

Most of Washington’s overseers were hired white hands from the local region, but a few enslaved men rose to this position of authority. For a brief time in the 1780s, three of Mount Vernon’s five farms had enslaved overseers. Reporting to Washington’s overall plantation manager, the overseers were responsible for supervising day-to-day operations of their fields, ensuring that the enslaved workers performed assigned duties thoroughly and attentively. For those who did not, overseers were also tasked with administering punishment. To his frustration, Washington found that hired workers who met his standards were rare indeed. He chided many overseers for drinking too much, sleeping too late, and neglecting their duties in favor of entertaining friends. By contrast, Gray’s work ethic and calm demeanor seem to have met with Washington’s approval. In 1793 Washington noted that 'Davy at Muddy hole carries on his business as well as the white Overseers, and with more quietness than any of them. With proper directions he will do very well.'

As overseer, Gray received certain privileges, such as leather breeches, occasional cash gifts, and extra quantities of pork after hogs were slaughtered. He and his wife lived in a house with a brick chimney, sturdier than the standard log cabins with wooden chimneys in which most enslaved field-workers resided. Being an overseer also gave Gray the power to advocate for his fellow workers. In 1793 Washington heard complaints from his slaves that his new method of distributing cornmeal was leaving them with less to eat. Initially skeptical, he changed his mind when Gray assured him 'that what his people received was not sufficient, and thatŠ—_several of them would often be without a mouthful for a day, and sometimesŠ—_two days.'

After Washington died in 1799, Gray was among the hired and enslaved workers who were outfitted with mourning clothes for the funeral. Because they were owned by the Custis estate, neither Gray nor his wife was freed by the emancipation provision in Washington’s will. A remarkable handwritten letter by President Washington regarding his vast Mount Vernon estate. - Shipping Info

-

Bidder is liable for shipping and handling and providing accurate information as to shipping or delivery locations and arranging for such. RR Auction is unable to combine purchases from other auctions or affiliates into one package for shipping purposes. Lots won will be shipped in a commercially reasonable time after payment in good funds for the merchandise and the shipping fees are received or credit extended, except when third-party shipment occurs. Bidder agrees that service and handling charges related to shipping items which are not pre-paid may be charged to a credit card on file with RR Auction. Successful international Bidders shall provide written shipping instructions, including specified Customs declarations, to RR Auction for any lots to be delivered outside of the United States. NOTE: Declaration value shall be the item’(s) hammer price and RR Auction shall use the correct harmonized code for the lot. Domestic Bidders on lots designated for third-party shipment must designate the common carrier, accept risk of loss, and prepay shipping costs.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB