George S. Patton Typed Letter Signed

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $5 |

| $50 | $10 |

| $200 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

About Auction

Oct 12, 2022

RR Auction support@rrauction.com

- Lot Description

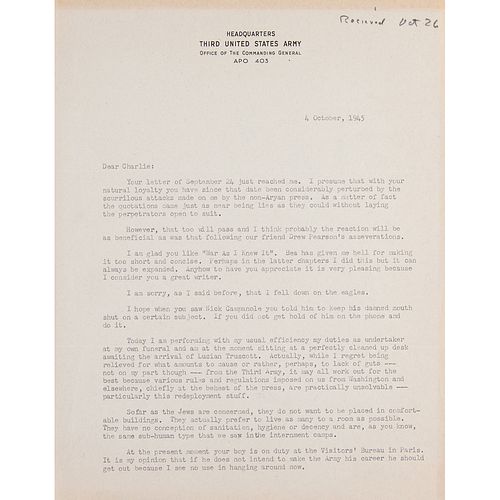

TLS signed “G. S. Patton, Jr.,” two pages, 8.25 x 10.5, Headquarters, Third United States Army, Office of the Commanding General letterhead, October 4, 1945. An astoundingly frank and revealing letter to his former aide, Lt. Col. Charles R. Codman, exposing Patton's isolation and depression following the end of the war in Europe, and revealing a bitter anti-Semitism. At this time, General Patton, who not long before had been instrumental in securing the Allied victory in Europe, was profoundly out of favor with both his military superiors and the civilian press corps. Critics and many former colleagues were shocked by Patton's insinuation that Schutzstaffel (or SS) troops were typically no different from conscripts in other armies and by his dismissive treatment of Displaced Persons. After a combative press conference on September 22nd, stories appeared in a number of stateside newspapers blaming Patton for the appalling conditions at many camps for Displaced Persons, many of whom were Jews. The press also reported that General Eisenhower ordered Patton to improve the camps under his area of command and also ordered him to attend a Yom Kippur service. A week after the press conference, on September 29th, Ike transferred Patton to a minor post with the Fifteenth Army in Bad Nauheim.

In this letter, Patton reveals his anger and frustration to his devoted aide. “I presume that with your natural loyalty you have been considerably perturbed by the scurrilous attacks made on me by the non-Aryan press. As a matter of fact the quotations came just as near being lies as they could without laying the perpetrators open to suit.” Patton sees better days ahead, though, as he indicates with an allusion to the controversial journalist who first reported Patton's slapping of hospitalized soldier Charles Kuhl: “However, that too will pass and the reaction will be as beneficial as was that following our friend Drew Pearson's asseverations.”

After apologizing for not being able to wrangle Codman a promotion to full colonel (“I am sorry, as I said before, that I fell down on the eagles”), Patton describes his situation as he prepares to move to his new assignment. His first comment in this paragraph, though, could apply to the recent management of his career as a whole: “Today I am performing with my usual efficiency my duties as undertaker at my own funeral and am at the moment sitting at a perfectly cleaned desk awaiting the arrival of Lucian Truscott. Actually, while I regret being relieved for what amounts to cause or rather, perhaps, to lack of guts—not on my part though—from the Third Army, it may all work out for the best because various rules and regulations imposed on us from Washington and elsewhere, chiefly at the behest of the press, are practically unsolvable—particularly this redeployment stuff.”

Addressing the question of the state of the camps for Displaced Persons, Patton does not moderate his language. “So far as the Jews are concerned, they do not want to be placed in comfortable buildings. They actually prefer to live as many to a room as possible. They have no conception of sanitation, hygiene or decency and are, as you know, the same sub-human types that we saw in the internment camps.”

After advising that Codman's son get out of the Army unless he intends on making it his career, Patton turns, with characteristic candor, to the political implications of the situation in Europe, especially as regards the Soviet Union. “I am really very fearful of repercussions which will occur this winter and I am certain we are being completely hoodwinked by the degenerate descendants of Genghis Khan. People who talk about peace should visit Europe, where, as I believe the Lord said, I bring you not peace but the sword. The envy, hatred, malice and uncharitableness in Europe passes belief.”

In closing, Patton observes, "I could say a good many more things but even yet fear censoring, though it is not supposed to exist, so shall refrain until I see you. My new job in the Fifteenth Army is really literary rather than military and has the advantage of getting me out of the limelight.” Patton would not see Codman again; on December 9th, the former was involved in a wreck of military vehicles and died of his injuries 12 days later. In fine condition. Accompanied by a custom beige cloth-bound presentation folder with slipcase.

Many theories have been offered for Patton's erratic behavior and statements near the end of his life. After the Pacific War was won, Patton famously noted in his diary, ‘Yet another war has come to an end, and with it my usefulness to the world.’ One biographer, Carlo D'Este, wrote that ‘it seems virtually inevitable…that Patton experienced some type of brain damage from too many head injuries,’ including a nasty polo accident in 1936. But in The Pattons: A Personal History of an American Family, the General's grandson, Robert H. Patton, stated, ‘The injection of anti-Semitism into his perception of the political dynamic of the occupation signaled his ultimate loss of moral bearings.’ A dark and disturbing letter written three days before Patton was officially relieved of command of the Third Army. - Shipping Info

-

Bidder is liable for shipping and handling and providing accurate information as to shipping or delivery locations and arranging for such. RR Auction is unable to combine purchases from other auctions or affiliates into one package for shipping purposes. Lots won will be shipped in a commercially reasonable time after payment in good funds for the merchandise and the shipping fees are received or credit extended, except when third-party shipment occurs. Bidder agrees that service and handling charges related to shipping items which are not pre-paid may be charged to a credit card on file with RR Auction. Successful international Bidders shall provide written shipping instructions, including specified Customs declarations, to RR Auction for any lots to be delivered outside of the United States. NOTE: Declaration value shall be the item’(s) hammer price and RR Auction shall use the correct harmonized code for the lot. Domestic Bidders on lots designated for third-party shipment must designate the common carrier, accept risk of loss, and prepay shipping costs.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB