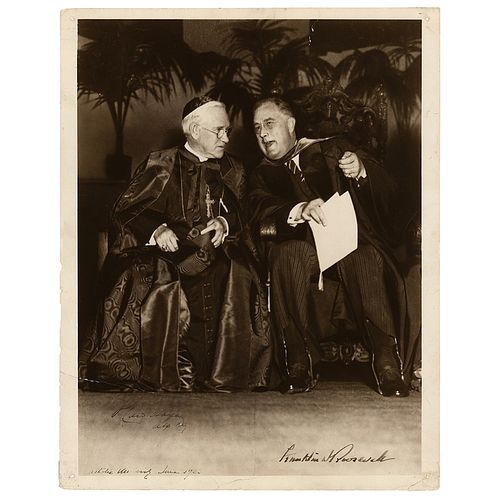

Franklin D. Roosevelt Signed Photograph as President

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $5 |

| $50 | $10 |

| $200 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

About Auction

Jun 23, 2022

RR Auction support@rrauction.com

- Lot Description

Oversized vintage matte-finish 11 x 15 photo of President Franklin D. Roosevelt seated and talking with Patrick Cardinal Hayes, the Archbishop of New York, at Catholic University on June 13, 1933, signed nicely in fountain pen as president, “Franklin D. Roosevelt.” The photo is also signed by Hayes, who adds the date and location below. In very good to fine condition, with scattered creasing, tack holes to the corners, and a tear to the top edge. So as not to draw attention to Roosevelt’s polio and subsequent disability, great care was taken to prevent any photos from being taken of the president wearing his braces or in his wheelchair. Photos depicting as much remain very rare, with signed examples virtually nonexistent.

Roosevelt became permanently paralyzed from the waist down after contracting polio at the age of 39 during a family trip to Canada in 1921. Unwilling to acquiesce to this immobile fate, he spent the rest of his life trying to recover—he spent the next three years searching for any means possible to walk again, concerned that this inability would affect his political career. Having exhausted most other options, he heard about a young man who had shown improvement after a course of hydrotherapy in the mineral-rich waters at a Georgia resort. It was then, in 1924, that FDR famously traveled to Warm Springs, Georgia, where the immersion in warm water was one of the few things that seemed to ease his pain-shortly thereafter he purchased the resort and developed it into what became a world-famous polio treatment center—the Georgia Warm Springs Foundation, still in operation today as the Roosevelt Warm Springs Institute for Rehabilitation. It was at Warm Springs that he was able to strengthen his withered leg and hip muscles and eventually found himself able to stand on his own, at which point he fitted his hips and legs with iron braces and laboriously taught himself to walk a short distance by swiveling his torso while supporting himself with a cane.

In 1933, there was a spirit of cooperation and support exhibited by American Catholics for the New Deal, which went beyond platitudes on the supposed similarity of the movement with the teaching of the Church, which found the President and his program alike entirely praiseworthy. On his part, Roosevelt demonstrated an acute awareness of his Catholic backers and managed to solidify this support through his cordial relationship with the American hierarchy, his availability to the Church, and his patronage policies.

If President Roosevelt's appointment policy helped his image among American Catholics in 1933, of added significance were the direct contacts he sought with the Church during his first year in office. One of his more notable public contacts was his acceptance of an honorary degree from Catholic University on June 14th.

The major speech of the occasion was made by Patrick Cardinal Hayes of New York, an old acquaintance of the new president, who prefaced his remarks with congratulations to a president who was ‘moving forward with courage and intelligence’ to combat the crisis of the depression. ‘Your actions,’ the Cardinal continued, ‘spring from but one motive, namely, the advancement of the Common Good.’

President Roosevelt, who had not planned to speak, offered a few impromptu remarks, referring to the Cardinal as ‘my old friend and neighbor from New York,’ and commenting that his own presence among the great dignitaries of the Church, and the added fact that it was Flag Day made a ‘happy combination.' - Shipping Info

-

Bidder is liable for shipping and handling and providing accurate information as to shipping or delivery locations and arranging for such. RR Auction is unable to combine purchases from other auctions or affiliates into one package for shipping purposes. Lots won will be shipped in a commercially reasonable time after payment in good funds for the merchandise and the shipping fees are received or credit extended, except when third-party shipment occurs. Bidder agrees that service and handling charges related to shipping items which are not pre-paid may be charged to a credit card on file with RR Auction. Successful international Bidders shall provide written shipping instructions, including specified Customs declarations, to RR Auction for any lots to be delivered outside of the United States. NOTE: Declaration value shall be the item’(s) hammer price and RR Auction shall use the correct harmonized code for the lot. Domestic Bidders on lots designated for third-party shipment must designate the common carrier, accept risk of loss, and prepay shipping costs.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB