Charles Lindbergh and Billy Wilder: The Spirit of St. Louis Movie Correspondence Archive

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $5 |

| $50 | $10 |

| $200 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

About Auction

Jul 12, 2023

RR Auction support@rrauction.com

- Lot Description

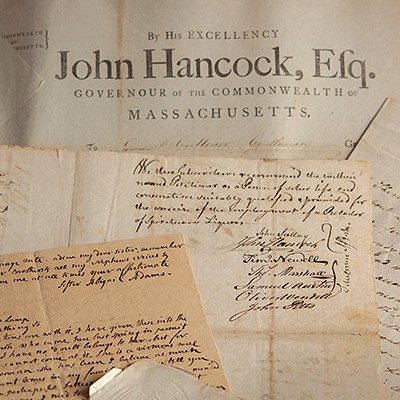

Remarkable archive of correspondence and photography related to the production of the 1957 film The Spirit of St. Louis, directed by Billy Wilder, produced by Leland Hayward, and starring James Stewart as Charles Lindbergh, adapted from Lindbergh's own Pulitzer Prize-winning 1953 autobiographical account of his historic solo transatlantic flight. The highlights of the archive are two TLSs from Lindbergh to Wilder, plus various telegrams, letters by Leland Hayward, Billy Wilder's retained carbon copies of correspondence sent to Lindbergh, and several photographs.

The key piece is a lengthy TLS by Charles Lindbergh, signed "Charles," four pages, 8.5 x 11, May 20, 1954, to Billy Wilder, responding to some questions pertaining to his life and career. In part: "The only life insurance I ever carried consists of a $10,000 war-risk policy I took out as a Flying Cadet in 1924. Being a government policy, it was not limited in regard to types of risk involved. I did consider, about 1926-27, taking out a life insurance policy (civil) but considered the rate for a professional pilot too high. Insurance companies, at the time, were dubious about all flying risks. (In 1929-30 I inquired about insurance costs for my Lockheed Sirius plane, and found that crash-damage insurance would cost me about $5,000 per year. At this rate, I calculated that I would have to wash out one plane about every three years to break even—the Sirius cost just over $15,000—so I decided to carry my own crash-damage insurance, which has turned out to be highly profitable over the years.

The great skeptics about the success of my flight to Paris, in 1927, aside from laymen, were among engineers and pilots. The papers of the time carry a number of statements about the impossibility of my undertaking from both mechanical and physical standpoints, made by professional people.

In regard to Levine's motives, he had purchased the Bellanca, together with manufacturing rights, from the Wright Aeronautical Corp., and planned to manufacture the plane‰Û_The cost of purchase was extraordinarily low, and I am under the impression that the price of $25,000 he asked for the plane would have covered his complete outlay and left him with the manufacturing rights in the clear‰Û_

When the Contract Air Mail routes began, in 1926, the carriers were paid by the Post Office per pound of mail carried, including sack weight, according to their bid on the particular route. There was no other government subsidy. Deficits were met by the company carrying the mail. In the case of C.A.M.#2 (St. Louis-Chicago), the St. Louis banks assisted with the deficit. The air mail cut down on bank-clearance time for St. Louis, even in 1926.

In regard to my will, I had one some time before the Paris flight, made out to my mother as beneficiary—a pretty simple affair, not involving very much money, drafted by a local Missouri lawyer who lived near Lambert Field, in 1925 or 26.

Concerning accuracy in transposing 'The Spirit of St. Louis' from book to film, of course exact accuracy is impossible. This is a subject which will probably require considerable discussion, and about which I have great confidence in your and Leland's judgment. I was determined to make my book as accurate as I could, and spent a huge amount of time in research and correspondence in order to do so. But even here, in order to gain accuracy of impression, I had to sacrifice some accuracy of fact, and each has its own validity. In the book, I adopted the policy of making no statement which was not factual to the best of my knowledge; but I frequently used factual statements out of their factual sequence. For instance, the flashbacks in the book are accurate in themselves but quite out of sequence both as to life and as to thought on the flight. My mind was not working in that sequence, and the mind need not go into the clarity of detail which is necessary for the conveying of impression to the reader. But by using these flashbacks, I was able to give my readers a truth of impression—to carry them in the cockpit with me—as I could have done in no other way. (I outlined this procedure in the preface.)

Personally, I feel that a film should have much more freedom of impression than a book of the type of 'The Spirit of St. Louis.' I think there is a validity to Goldwyn's 'Hans Christian Anderson' which starts out by saying, as I recall, that it is 'a fairy tale about a fairy tale,' and, on the other end, there is a quality to 'Martin Luther,' which, I am told is unusually accurate for a film of this type. It seems obvious to me that we want a sound framework of factual accuracy for 'The Spirit of St. Louis,' and that many of the facts connected with the flight are more interesting than any fiction by which they could be replaced. But within this framework, I think there should be a good deal of leeway. Factual impression seems more important, to me, in a film than in a book, by a big margin. The book is the factual record; possibly the film should always be the impressionistic one. Beyond a point, I am convinced that striving for exact accuracy will defeat itself by its very impossibility of attainment; the very attempt will overemphasize the inevitable failure‰Û_

I hope you received the New York Times photostats in good condition. I have no further need for them‰Û_While I rate the N. Y. Times as the best large newspaper in the United States, it is by no means immune to the waywardness of its profession, and some of the reports about my flight and preparation are not accurate—even impressionistically!" Lindbergh pens the last two words in his own hand. Includes Wilder's retained carbon copy of the letter that prompted this response, dated May 14, 1954.

In the one-page Lindbergh letter, also signed "Charles," dated May 20, 1955, he responds to further inquiries from Wilder, in part: "The St. Louis-Chicago services started in mid-April, and I left for California in late February. That makes about ten months. I probably averaged about nine round trips a month, or say ninety in all. At three hours per one-way trip (it was a little over, as I remember), that would total 540 hours. Let's say that I had between five and six hundred hours as an air-mail pilot; will that be accurate enough for purposes of the film? Now I'll make an attempt at the explanation of trans-Atlantic navigation you ask for: If you will turn to page 154 (The Spirit of St. Louis), I'll try to carry on in more detail, starting near the end of the page. 'If you haven't got a radio or a sextant, what's going to keep you from getting lost?' 'It won't matter if I'm a couple hundred miles off course, if I've got plenty of gasoline.' 'Why won't it?' 'I can't very well miss the whole coast of Europe. I'll just set a new course for Paris, when I find out where I am.' 'How are you going to know where you are?' 'I can tell a lot by the coast, when I strike it—mountains, bays, rivers, things like that. If there's fog on the coast, I'll fly low over the first town I come to, I can tell what country I'm over by the language on the signs.'" Includes Wilder's retained carbon copy of the letter that prompted this response, dated May 18, 1955.

Although unsigned, contemporary copies of two of Wilder's telegrams to Lindbergh offer interesting content: the first, of January 26, 1954, reads, "Dear Colonel: This is to congratulate myself to have been entrusted with putting your superb Spirit of St. Louis on film. I am thrilled and proud and most grateful," with Lindbergh's telegram in responses: "Have been greatly impressed by your films. Am looking forward to meeting you soon and to an extremely interesting and pleasant relationship"; Wilder's second telegram offers humorous congratulations on his Pulitzer Prize for the book, alluding to Ernest Hemingway's recent African plane crashes: "Congratulations on your triumph over Hemingway in the literary field and may I remind you that earlier in the year you were also clearly established as the superior flier."

Further materials include: a Warner Bros. document related to the film's financing and distribution agreements, signed in blue ballpoint by Billy Wilder and Leland Hayward; a telegram from Richard E. Byrd, complaining about the portrayal of his transatlantic flight ("Our flight was, I believe, not so bad or so useless as it has sometimes been depicted"); several letters signed by Leland Hayward, offering lengthy commentary on the film, the tepid response it received from preview audiences, and suggested changes; and eight original photographs, showing Wilder with a Spirit of St. Louis replica built for the film, meeting with Lindbergh and Stewart, and several similar shots. In overall fine condition.

This remarkable archive demonstrates the painstaking measures taken to ensure the accuracy and quality of the screen adaptation of The Spirit of St. Louis, which was produced at a cost of $7 million—$1.3 million of which was dedicated to the construction of three replicas of Lindbergh's famous plane. Offering a fascinating behind-the-scenes look at the production of a significant film, this is a unique archive that crosses the boundary between history and popular culture. - Shipping Info

-

Bidder is liable for shipping and handling and providing accurate information as to shipping or delivery locations and arranging for such. RR Auction is unable to combine purchases from other auctions or affiliates into one package for shipping purposes. Lots won will be shipped in a commercially reasonable time after payment in good funds for the merchandise and the shipping fees are received or credit extended, except when third-party shipment occurs. Bidder agrees that service and handling charges related to shipping items which are not pre-paid may be charged to a credit card on file with RR Auction. Successful international Bidders shall provide written shipping instructions, including specified Customs declarations, to RR Auction for any lots to be delivered outside of the United States. NOTE: Declaration value shall be the item’(s) hammer price and RR Auction shall use the correct harmonized code for the lot. Domestic Bidders on lots designated for third-party shipment must designate the common carrier, accept risk of loss, and prepay shipping costs.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB