Andrew Jackson ALS on Mudslinging in 1828: "Truth is Mighty"

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $5 |

| $50 | $10 |

| $200 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

About Auction

Apr 12, 2023

RR Auction support@rrauction.com

- Lot Description

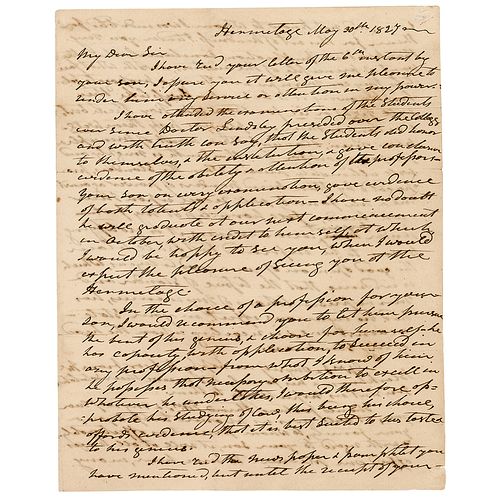

ALS, three pages on two adjoining sheets, 7.75 x 9.75, May 30, 1827. Handwritten letter to William Douglass, a friend and political supporter in Louisville, Kentucky, offering advice for his college-aged son and lashing out against libelous pamphleteers, slandering his good name in advance of the 1828 presidential election.

In full: "I have rec'd your letter of the 6th instant by your son, I assure you it will give me pleasure to render him any service or attention in my power. I have attended the examinations of the Students ever since Doctor Lindsley presided over the College, and with truth can say, that the Students did honor to themselves, & the institution, & gave conclusive evidence of the ability & attention of the professors—Your son on every examination, gave evidence of both talents & application—I have no doubt he will graduate at our next commencement in October, with credit to himself, at which, I would be happy to see you, when I would expect the pleasure of seeing you at the Hermitage.

In the choice of a profession for your son, I would recommend you to let him pursue the best of his genius, & choose for himself—he has capacity, with application, to succeed in any profession—from what I know of him he possesses that necessary ambition to excell in whatever he undertakes, I would therefore approbate his studying of law, this being his choice, affords evidence, that it is best suited to his tastes & to his genius.

I have rec'd the news paper & pamphlet you have mentioned, but until the receipt of your letter, did not know to whom I was indebted for them—for this act of kindness I tender you my thanks—These publications conclusively show the want of principle of the authors, & with what facility they can misrepresent things, & propagate falsehood, knowing it to be such—Swiss like they will fight or lie for those who pay them best, & as long as their employers pay them well—poor men, I lament their want of principle & proper regard for truth—Truth is mighty and will ultimately prevail, when the slanders, propagated by these hired panders of power against me or my family, will recoil upon their own heads, & fall harmless at my feet—Under present circumstances, it is gratifying to me to be informed that I still retain the good opinion of your good Citizens, which is evidence that the tissue of slander and misrepresentations of my enemies, has had no injurious effect on your State—against me, & is recoiling upon the head on my slanderers.

Mrs. J & myself are happy to hear from Mr. Blackburn & his family & to receive their salutations, present us respectfully to them. Should fortune throw Mrs. J & myself near you, it will give us pleasure to visit you, & your family, to whom present us affectionately—with regard to your son, it will at all times afford me pleasure to serve him, in any way I may have it in my power, & only regret that I have not had more of his company at the Hermitage." Addressed on the integral leaf in Jackson's own hand. In very good to fine condition, with minor paper loss along the edges, and old tape reinforcements to fold splits on the integral address leaf.

Published in Volume VI of The Papers of Andrew Jackson: 1825-1828 (p. 327-328, University of Tennessee Press, 1980).

Andrew Jackson writes to his family friend William Douglass as the 1828 presidential campaign gained momentum in mid-1827. Although Jackson had won the popular vote in 1824, the election was inconclusive as no candidate won a majority of the electoral vote. With the decision placed before the House, John Quincy Adams struck a so-called 'corrupt bargain' with Henry Clay—promising an appointment as secretary of state—to earn his place in the White House. The 1828 campaign began nearly as soon as Adams's presidency started, and was characterized by toxic mudslinging in the press that grew increasingly energized as the election approached.

Jackson, campaigning as an anti-corruption populist, stood on his record as a war hero and built a diverse coalition of support throughout the nation. Adams supporters decried him as a slaver, murderer of Native Americans, unhinged duelist, and adulterer; Jacksonians, in turn, called Adams a corrupt product of nepotism, claiming misuse of public funds. Partisan newspapers and sensationalist pamphleteers worked diligently to attack and counterattack in what became one of the ugliest electoral brawls of the 19th century.

In this letter, Jackson responds to the slander by proclaiming that "truth will prevail," and is glad to hear that he retains popularity in Kentucky. He would go on to take 15 states—including the South in its entirety—in a landslide victory. In spite of the win, the partisan attacks left Jackson incredibly bitter, and when his wife Rachel died suddenly days before his inauguration, he blamed the stressful campaign as a contributing factor. - Shipping Info

-

Bidder is liable for shipping and handling and providing accurate information as to shipping or delivery locations and arranging for such. RR Auction is unable to combine purchases from other auctions or affiliates into one package for shipping purposes. Lots won will be shipped in a commercially reasonable time after payment in good funds for the merchandise and the shipping fees are received or credit extended, except when third-party shipment occurs. Bidder agrees that service and handling charges related to shipping items which are not pre-paid may be charged to a credit card on file with RR Auction. Successful international Bidders shall provide written shipping instructions, including specified Customs declarations, to RR Auction for any lots to be delivered outside of the United States. NOTE: Declaration value shall be the item’(s) hammer price and RR Auction shall use the correct harmonized code for the lot. Domestic Bidders on lots designated for third-party shipment must designate the common carrier, accept risk of loss, and prepay shipping costs.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB