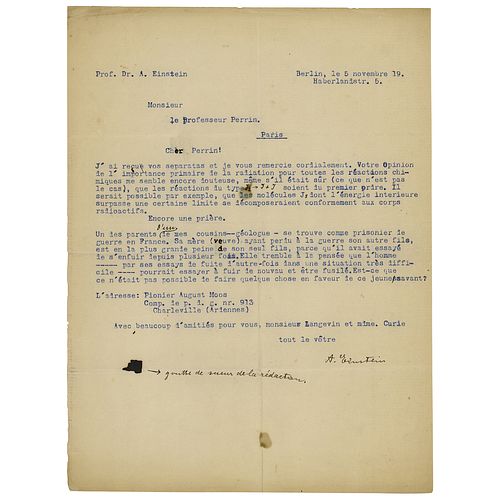

Albert Einstein Typed Letter Signed

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $5 |

| $50 | $10 |

| $200 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

About Auction

Jul 13, 2022

RR Auction support@rrauction.com

- Lot Description

TLS in French, signed “A. Einstein,” one page, 8.25 x 11, November 5, 1919. Letter to Professor Jean Baptiste Perrin, who would go on to win the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1926 for his work on the atomic structure of matter. In part (translated): "Your opinion of the primary importance of radiation for all chemical reactions still seems to me dubious, even if it was certain (which it was not) that reactions of the type J² - J+J [added by hand] are of the first order. It would be possible, for example, that J² molecules whose internal energy exceeds a certain limit would decompose in accordance with radioactive bodies.

Now a prayer. One of the parents of one of my cousins—a geologist—is a prisoner of war in France. His (widowed) mother, having lost her other son in the war, is in the greatest pain of her only son, because he had tried to flee several times. She shudders at the thought that the man—through his old efforts to flee in a very difficult situation—might try to flee again and be shot. Wouldn't it be possible to do something for this young scientist?" He goes on to give the address of August Moos, held in Charleville, Ardennes, and concludes by offering his "regards for you, Mr. Langevin and Mrs. Curie." Below, he curiously draws an arrow and writes, "bead of editorial sweat"—could his DNA be lurking on this page? In fine condition.

A distant cousin of Albert Einstein, the geologist August Moos volunteered in the German infantry at the start of the First World War in 1914. After being taken prisoner in 1915, he made several attempts to escape which resulted in a sentence that prevented his release after the armistice of 1918. His mother asked for help from Einstein, who turned to his friend Jean Perrin, as well as mathematician and statesman Paul Painlevé, asking them to intercede. Moos was finally released in February 1920. He would work as an oil geologist in the interwar period, before being tragically arrested due to his Jewish heritage under the Nazi regime. Moos would die in the Buchenwald concentration camp during World War II.

In addition to this important family and political content, Einstein comments on a theory that Perrin had developed in which all chemical transformations (including radioactive decay) are triggered by radiation, calling it "dubious." Also significant is the date: one day before the official report of Eddington's expedition debuted before the Royal Society of London, confirming Einstein's theory of general relativity. Widespread newspaper coverage of the results vaulted Einstein into immediate international fame. An altogether remarkable letter from one Nobel Prize winner to another. - Shipping Info

-

Bidder is liable for shipping and handling and providing accurate information as to shipping or delivery locations and arranging for such. RR Auction is unable to combine purchases from other auctions or affiliates into one package for shipping purposes. Lots won will be shipped in a commercially reasonable time after payment in good funds for the merchandise and the shipping fees are received or credit extended, except when third-party shipment occurs. Bidder agrees that service and handling charges related to shipping items which are not pre-paid may be charged to a credit card on file with RR Auction. Successful international Bidders shall provide written shipping instructions, including specified Customs declarations, to RR Auction for any lots to be delivered outside of the United States. NOTE: Declaration value shall be the item’(s) hammer price and RR Auction shall use the correct harmonized code for the lot. Domestic Bidders on lots designated for third-party shipment must designate the common carrier, accept risk of loss, and prepay shipping costs.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB