Abraham Lincoln Letter Signed as President on Fort Pillow Massacre of Black Soldiers by Rebels

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $5 |

| $50 | $10 |

| $200 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

About Auction

Feb 22, 2024

RR Auction's first-ever February installment of its Remarkable Rarities series brings some 50+ pieces of history to the auction block, representing the most elusive and extraordinary items offered all year. RR Auction support@rrauction.com

- Lot Description

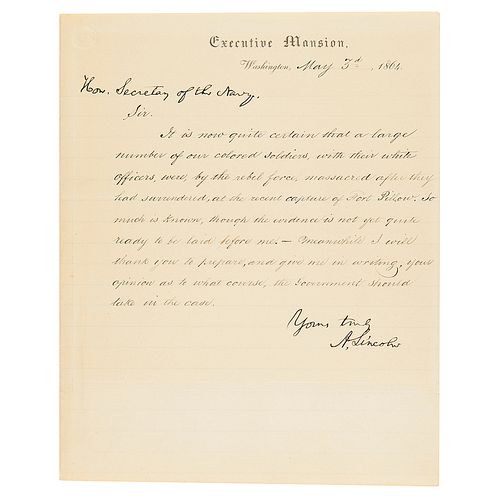

Civil War-dated LS as president, signed “Yours truly, A. Lincoln,” one page, 8 x 10, Executive Mansion letterhead, May 3, 1864. Letter addressed in Lincoln's hand to "Hon. Secretary of the Navy," Gideon Welles, regarding the devastating massacre of Union soldiers (many of them part of the United States Colored Troops) at Fort Pillow on April 12, 1864. In full: "It is now quite certain that a large number of our colored soldiers, with their white officers, were, by the rebel force, massacred after they had surrendered, at the recent capture of Fort Pillow. So much is known, though the evidence is not yet quite ready to be laid before me.—Meanwhile I will thank you to prepare, and give me in writing, your opinion as to what course, the government should take in the case." In fine condition, with a very light, uniform block of toning.

On April 12, 1864, Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest—an expert cavalryman and future founder of the Ku Klux Klan—led a raid on Fort Pillow, an outpost in west Tennessee that had been held by federal troops for about two years. The Union garrison there numbered about 600 men, divided almost evenly between black and white troops. Forrest's troops outnumbered them three-to-one, and had the fort surrounded. After several hours of sharpshooters' repartee—which took the life of the fort's commander, Major Lionel F. Booth—Forrest sent a note demanding surrender. The ultimatum was delivered to Maj. William F. Bradford, who asked for an hour to decide. Forrest ceded only 20 minutes, and Bradford replied: 'I will not surrender.'

Forrest then launched a brutal assault on the fort, quickly overwhelming the Union forces. Most of the garrison tried to surrender, throwing down their arms and begging for mercy—only to be fired upon and bayoneted by the attacking rebels. An April 16th report from the New York Times offers a vivid description of the carnage: 'Immediately upon the surrender ensued a scene which utterly baffles description. Up to that time, comparatively few of our men had been killed; but, insatiate as fiends, bloodthirsty as devils incarnate, the Confederates commenced an indiscriminate butchery of the whites and blacks, including those of both colors who had been previously wounded....Both white and black were bayoneted, shot or sabred; even dead bodies were horribly mutilated, and children of seven and eight years and several negro women killed in cold blood. Soldiers unable to speak from wounds were shot dead, and their bodies rolled down the banks into the river. The dead and wounded negroes were piled in heaps and burned, and several citizens who had joined our forces for protection were killed or wounded. Out of the garrison of six hundred, only two hundred remained alive.'

President Lincoln first addressed the Fort Pillow incident during a speech at the Baltimore Sanitary Fair on April 18th, pledging that these deaths would not be in vain: 'A painful rumor, true I fear, has reached us of the massacre by the rebel forces at Fort Pillow, in the west end of Tennessee on the Mississippi river of some three hundred colored soldiers and white officers who had just been overpowered by their assailants. There seems to be some anxiety in the public mind whether the government is doing its duty to the colored soldier, and to the service, at this point. At the beginning of the war, and for some time, the use of colored troops was not contemplated; and how the change of purpose was wrought, I will not now take time to explain. Upon a clear conviction of duty I resolved to turn that element of strength to account; and I am responsible for it to the American people, to the Christian world, to history, and on my final account to God. Having determined to use the negro as a soldier, there is no way but to give him all the protection given to any other soldier.... We are having the Fort Pillow affair thoroughly investigated....If there has been the massacre of three hundred there, or even the tenth part of three hundred, it will be conclusively proved; and being so proved, the retribution shall as surely come. It will be a matter of grave consideration in what exact course to apply the retribution; but in the supposed case, it must come.'

The Battle of Fort Pillow became the subject of an inquiry by the Congressional Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, as well as the subject of numerous reports in the press. Frank Leslie's Illustrated Weekly and Harper's Weekly were among the nationally circulated periodicals that publicized the horrors of the massacre. Lincoln struggled to find an appropriate response as the truth about the massacre emerged, turning to the members of his cabinet for counsel. As documented in the Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume 7 (ed. Basler), Lincoln sent this text to all members of his cabinet, asking for their advice regarding the government's course of action following the Fort Pillow events. Per Basler's annotations: 'All members agreed that the Confederate government should be called on to avow or disavow the massacre. Seward, Chase, Stanton, and Welles agreed in advising that Confederate prisoners equal in numbers to the Union troops massacred should be set apart as hostages, to be executed if the Confederate government avowed the massacre. Usher, Bates, and Blair advised no retaliation against innocent hostages, but advised that orders be issued to commanders to execute the actual offenders (Forrest and any of his command) if captured.'

On May 6th, President Lincoln held a cabinet meeting to review the various options that had been suggested. Gideon Welles played a principal role in the affair, and provides an overview of the discussion in his diary entry for that date: 'Between Mr. Bates and Mr. Blair a suggestion came out that met my views better than anything that had previously been offered. It is that the President should by proclamation declare the officers who had command at the massacre outlaws, and require any of our officers who may capture them, to detain them in custody and not exchange them, but hold them to punishment...In a conversation that followed the reading of our papers, I expressed myself favorable to this new suggestion, which relieved the subject of much of the difficulty. It avoids communication with the Rebel authorities. Takes the matter in our own hands. We get rid of the barbarity of retaliation.'

All feared that eye-for-an-eye retaliation—the execution of a like number of rebel soldiers and officers—would cascade into an even more vicious war. In 1885, Frederick Douglass recalled his August 1864 audience with President Lincoln to urge retaliation against the South for its brutality against black Union soldiers: 'I shall never forget the benignant expression of his face, the tearful look of his eye, and quiver in his voice when he deprecated a resort to retaliatory measures. 'Once begun,' said he, 'I do not know where such a measure would stop.' He said he could not take men out and kill them in cold blood for what was done by others. If he could get hold of the persons who were guilty of killing the colored prisoners in cold blood, the case would be different, but he could not kill the innocent for the guilty.'

Ultimately, Abraham Lincoln chose to take no action on the issue, and it was soon surpassed in the public mind by the successes of General U. S. Grant's Wilderness Campaign. Nevertheless, 'Remember Fort Pillow' became a rallying cry for the Union's black soldiers, and the tragic events may well have influenced President Lincoln’s implementation of a more radical abolition policy. His letter to his cabinet members reveals just one of the heavy subjects weighing on his mind as he fought to preserve the Union, his trust in his devoted 'team of rivals' cabinet, and the innate sense of justice that informed his decision making. A remarkable and historically significant letter signed by President Abraham Lincoln.

Provenance: Sotheby's New York, 26 June 2000, lot 73.

President Lincoln's handwritten draft of the text of this important letter resides in the Library of Congress. - Shipping Info

-

Bidder is liable for shipping and handling and providing accurate information as to shipping or delivery locations and arranging for such. RR Auction is unable to combine purchases from other auctions or affiliates into one package for shipping purposes. Lots won will be shipped in a commercially reasonable time after payment in good funds for the merchandise and the shipping fees are received or credit extended, except when third-party shipment occurs. Bidder agrees that service and handling charges related to shipping items which are not pre-paid may be charged to a credit card on file with RR Auction. Successful international Bidders shall provide written shipping instructions, including specified Customs declarations, to RR Auction for any lots to be delivered outside of the United States. NOTE: Declaration value shall be the item’(s) hammer price and RR Auction shall use the correct harmonized code for the lot. Domestic Bidders on lots designated for third-party shipment must designate the common carrier, accept risk of loss, and prepay shipping costs.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB