Abraham Lincoln Document Signed as President

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $5 |

| $50 | $10 |

| $200 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

About Auction

Aug 10, 2022

RR Auction support@rrauction.com

- Lot Description

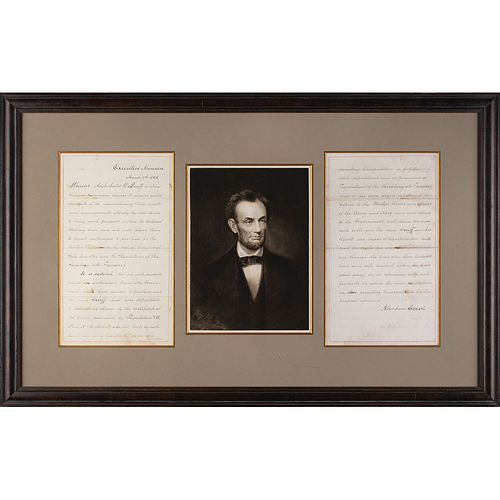

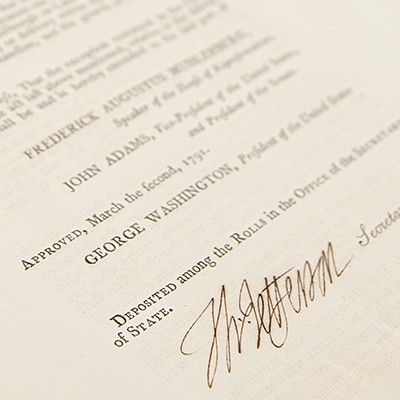

Important manuscript DS as president, two pages, 7.75 x 13.25, March 7, 1865. Significant document issued from the Executive Mansion, permitting trade across military lines during the Civil War. In part: "Where Archibald D. Grieff of New Orleans, Louisiana, claims to own or control products of the insurrectionary states and to have arrangements whereby he will be able to bring such products within the national military lines, and sell and deliver them to agents authorized to purchase for the United States under the act of Congress of July 2, 1864, and the regulations of the Secretary of the Treasury; It is ordered that all such products which an authorized agent of the government shall have agreed to purchase and the said Grieff shall have stipulated to deliver as shown by the certificate of the agent prescribed by Regulation VIIIŠ—_

And being transported or in store awaiting transportation in fulfillment of said stipulations and in pursuance of regulations of the Secretary of the Treasury, shall be free from seizure, detention or forfeiture to the United States, and officers of the army and navy and civil officers of the government will observe this order and will give the said Grieff and his agents and means of transportation and said products free and unmolested passage through the lines, other than blockaded lines, and safe contact within the lines while going for or returning with said products or while the said products are in store awaiting transportation for the purposes aforesaid." In fine condition, with scattered staining.

Few issues of commerce were more troublesome to President Lincoln than the question of Confederate cotton. The 'cash crop' was the bedrock of the Southern economy, and had been the United States' leading export in pre-war years. The Union's naval blockade, instituted by President Lincoln in April 1861, was designed to prevent the export of cotton to Europe and stifle the Confederacy's primary means of fundraising. However, the North still needed cotton for its textile mills, and plantations were overtaken as the Union armies marched further and further south. Confiscation acts passed by Congress allowed for federal seizure of these valuable properties-land, livestock, and cotton were among the chief spoils-and a special body of Treasury agents was appointed to administer these newfound assets. Additionally, businessmen from the North were eager to capitalize on cotton shortages created by the wartime economy. Cotton purchased for 20 cents a pound in New Orleans could be sold for $1.89 per pound in New York City.

Lincoln's leading generals, U. S. Grant and William T. Sherman, advocated for strict federal control over the cotton trade-it was virtually impossible to distinguish between Confederate cotton (subject to confiscation, and the purchase of which might support the rebel cause), and legitimate cotton (grown by planters loyal to the Union). This led to graft, bribery, and corruption among merchants operating between North and South. In spite of backlash from the military establishment, the Lincoln administration prevailed in establishing a permit system by which private agents served as the government's representatives in the purchase of cotton. An Act of Congress passed on July 2, 1864, formalized an arrangement where the US government could better regulate commerce between 'loyal and insurrectionary states, and to provide for the collection of captured and abandoned property and the prevention of frauds in States declared in insurrection.'

In September of 1864, an agent of the Bank of Louisiana by the name A. D. Grieff had written to Lincoln to request such a permit: 'The undersigned respectfully asks your excellency for a permit or authority in the proper form to proceed through the lines of the Federal army to Shreveport, near the mouth of Red River for the purpose of conveying goods not contraband and returning with 30,000 bales of cotton in accordance with the provisions of the act approved 1864. The above cotton was purchased by the State Bank of Louisiana under permits of General Butler and Shipley.'

It was not until the first quarter of 1865 that Lincoln began signing permits for new agents, but he indeed granted Grieff's request by the present document. It is one of just two examples of such a permit known to have entered the market in the last four decades.

Interestingly, the specific cotton in question became caught up in a legal battle shortly after President Lincoln's death. The Bank of Louisiana claimed it had legally purchased the cotton under permission of General Butler. Agents of the United States government claimed it was in fact contraband. The firm of Grieff and Zuntz are listed by name in the piece as agents of the bank. The New York Times reported on the case in October 1865: 'A prize suit of considerable interest was tried in the Admiralty Court of the United States at this place, in September. It was a suit for the recoveryŠ—_of cotton captured by a detachment of gunboats from Commodore Porter's Red River expeditionŠ—_The importance of this suit arisesŠ—_from the fact that the rulings of the Court, and the principles of international and domestic law presented by counsel in their elaborate arguments, must influence decisions in somewhat similar cases now before this and other courts of the United States for adjudication.' In the end, the Bank was ordered to forfeit this cotton. - Shipping Info

-

Bidder is liable for shipping and handling and providing accurate information as to shipping or delivery locations and arranging for such. RR Auction is unable to combine purchases from other auctions or affiliates into one package for shipping purposes. Lots won will be shipped in a commercially reasonable time after payment in good funds for the merchandise and the shipping fees are received or credit extended, except when third-party shipment occurs. Bidder agrees that service and handling charges related to shipping items which are not pre-paid may be charged to a credit card on file with RR Auction. Successful international Bidders shall provide written shipping instructions, including specified Customs declarations, to RR Auction for any lots to be delivered outside of the United States. NOTE: Declaration value shall be the item’(s) hammer price and RR Auction shall use the correct harmonized code for the lot. Domestic Bidders on lots designated for third-party shipment must designate the common carrier, accept risk of loss, and prepay shipping costs.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB