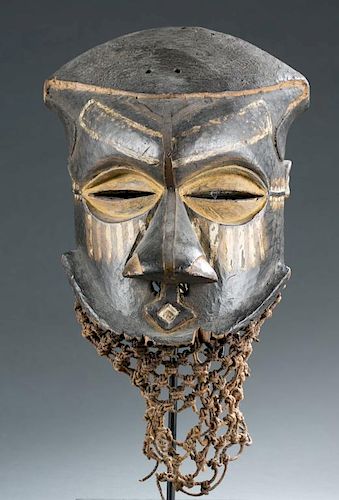

Kuba Mboom helmet mask

Lot 532

About Seller

Quinn's Auction Galleries

360 S. Washington Street

Falls Church, VA 22046

United States

Quinn's Auction Galleries is a full service auction and estate services company. We have a range of specialties, from fine art & antiques, to rare books & maps.

Categories

Estimate:

$22,000 - $25,000

Absentee vs Live bid

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $10 |

| $300 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $3,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $15,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,000 |

| $30,000 | $2,500 |

| $100,000 | $5,000 |

About Auction

By Quinn's Auction Galleries

Oct 1, 2016 - Oct 2, 2016

Set Reminder

2016-10-01 11:00:00

2016-10-02 11:00:00

America/New_York

Bidsquare

Bidsquare : Estate of Merton Simpson & Multi Estate Ethnographic

https://www.bidsquare.com/auctions/quinns/estate-of-merton-simpson-multi-estate-ethnographic-1779

Quinn's Auction Galleries dquinn@quinnsauction.com

Quinn's Auction Galleries dquinn@quinnsauction.com

- Lot Description

A Mboom helmet mask with yellow painted coffee bean shaped eyes, a full broad nose, a raised bulbous forehead, and a dome shaped element that expands as it extends to the top rear of the head. Parallel yellow lines decorate the cheeks under the eyes. A flange like form extends along the edge of the base of the mask. A yellow rectangular shape decorates the forehead. Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kuba. c.1900. 14 1/2"h.

Condition: Very good with nicks, abrasions and signs of wear

Provenance: Private Midwest Collector"Mark Felix Coll Brussels; Robert JacobsCollections Detroit Catalog Notes: This is a superb Kuba mask, it easily could be a 19th century example. “Bwoom is a wooden helmet mask elucidated by varied oral traditions. The Kuba feel that one "" 'understands' the why of something if one knows how it 'began'; something is known if it is explained"" (Vansina 1978:15). Thus Bwoom is the spirit first seen by nkan initiates; he is a hydrocephalic prince, a commoner, a pygmy, or one who opposes the king's authority. Two traditions trace Bwoom's origin to the reign of King Miko mi-Mbul, who had gone mad after killing the children of his precedessor. Although he finally became sane, Miko would lapse into madness each time he wore Mwaash aMbooy, the most important royal mask and until then the only one worn by the king himself. A pygmy offered the king Bwoom as an alternative. Suffering no ill effects with the new mask, Miko accepted it. A less dramatic version is that Miko, known as a great dancer, was simply seduced by the pygmy's despite its humble character. In both cases the King is credited with improvements to the mask that justify its inclusion in the royal repertoire (Cornet 1982:269). As inconsistent as they may seem, each account expresses an aspect of the mask or its character. The identification of Bwoom as a pygmy or a hydrocephalic man is often cited to explain the mask's enlarged forehead and broad nose. Bwoom appears in initiation and is always considered a spirit. The lowly origin of the character is reflected in its description: ""a person of low standing scarcely worthy of being embodied by the king"" (Cornet 1975:89) and conversely in its defiant performance opposite the regal Mwaash aMbooy. The two may act out a competition for the affections of the one female in the royal mask trio, Ngady mwaash aMbooy (Cornet 1982:255). Mwaash aM-booy's dance is calm and stately, while Bwoom acts with pride and aggression (Cornet 1982:255). The masks are easily differentiated by material, for Bwoom is carved from a single piece of wood and Mwaash aMbooy is made from cloth and raffia textiles. Bwoom appears on the nkan ""initiation fence"" of the Bushong (Vansina 1955:150-151) and in other initiation contexts. Little is known of this mask (or indeed most Kuba arts) outside of the royal Nsheng tradition. A royal mask, Bwoom is sometimes worn by the king. Yet unlike Mwaash aMbooy, Bwoom does not appear at funerals, and it is never interred with the king or other dignitaries (Cornet 1982:270). The costume is similar to that of Mwaash aMbooy: heavy with profuse layers of raffia-cloth, bead and cowrie decoration, leopard skins, anklets, armlets, and fresh leaves. Eagle feathers or other prestigious media are added to the crown of the head when the mask is danced. Despite regional variations, the Bwoom mask conforms to a distinct type. All styles feature strongly rendered proportions dominated by an enlarged brow, broad nose, and usually naturalistic ears. Typical features include the metal work on the forehead, cheeks, and mouth, bands of beads that embellish the face, and an expanse of beadwork at the temples and back of the head. Plate 8 has these plus patterned raffia-cloth covering the top of the head, with a fringe of hair. The blue beads set into the white band at the temples imitate ethnic tattoo patterns (Cornet 1982:266), and the design at the back of the head is one associated with royalty.” Randafricanart.com" - Shipping Info

-

Shipping and Handling Policy:

Quinn's Auctions ONLY ships with FedEx Domestic and USPS internationally. We do not ship Media Mail. Shipping costs are based on the weight of your lots and your location. We require a complete shipping address and phone number to process your shipping quote. You will receive your shipping quote in your invoice via your registered email with a tracking number if available. Once payment is received Quinns will ship items FedEx ground in the United States, USPS International or release items to an outside shipper.Quinn's Auctions reserves the right to recommend an outside shipper based on fragility and size of lot. We offer recommendations for outside shipping by trusted shippers if necessary. If using an outside shipper Quinn's Auctions is not responsible for damages by carriers or packers of purchased lots, whether or not recommended by Quinn's Auctions and will not be liable for any losses which result.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB