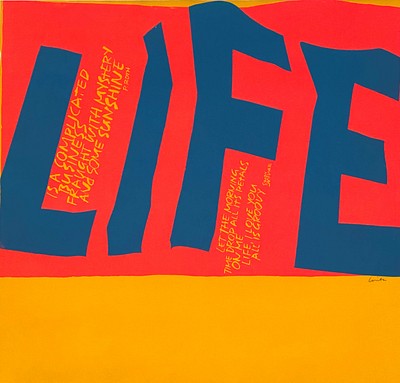

Witold Gordon (American, 1898-1968) Surrealist Painting

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $10 |

| $100 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,500 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $15,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Apr 30, 2023

Fine Art Auction - 35th Anniversary Myers Antiques auctions@myersfineart.com

- Lot Description

Witold Gordon (American, 1898-1968) Painting. Surrealist Trompe L'oeil Still Life. Oil on artist’s board realistically painted painting. Measures 12.5 inches high, 10.5 inches wide. Silver gilt frame measures 18.6 inches high, 16.5 inches wide. Signed lower left Witold Gordon. In good condition.

Witold Gordon was born in Poland in the 1880's, graduated from the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts and fled his homeland during the political upheaval of the early 1900's. His studies continued at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris and in Italy. He first came to the U.S. in 1914, settled in Manhattan, which was to be home until the early 1960s, and established his career as illustrator, designer and muralist.

Gordon had met Helena Rubenstein in Paris before coming to the United States, and for many years served as her design consultant on everything from cosmetics packages and advertising, to the Countess Rubenstein Salons and her private art collection. It is likely that his association with Madame Rubenstein was responsible for a series of editorial illustrations in the April, July and August 1915 issues of Vanity Fair; His drawings had the high fashion look we associate with the flapper era of the 1920's. Much to Helena Rubenstein's displeasure and ultimate jealousy (she was Mrs. Edward Titus at the time) Gordon met Marie Ouf, a Rouen debutante of the time. Marie and Witold began a liaison, sharing their lives, until their marriage in 1941, which in turn lasted until his death. A product of the early days of their love, is a hand illustrated copy of Les Fleur du Mal dedicated to Marie on her birthday, 16 July 1920. It is appropriate at this point to add that Gordon had married before meeting Marie and had a son by his first wife. She did not grant him a divorce until the mid-1930's. Witold continued to support her until her death in the early 1950's. It was the great sadness in Gordon's life that his son met with him but once as an adult, after his mother's death and voiced nothing but hatred for this very gentle and lovable man, his father.

Gordon would try his hand at all aspects of graphic arts, and areas of design beyond those limits. He did the costume designs for Fortza del Destino mounted by the Metropolitan Opera for Caruso in 1918. These costumes were in use until 1944. He started designing theater posters. In 1929 he illustrated the Horace Livright collector's edition of Manuel Komroff's Adventures of Marco Polo. A complete set of these stylish illustrations reside in the collection of the Cooper Hewitt Museum of The Smithsonian Institution.

The early 30's were very busy years for Gordon working with Donald Desky on interiors for parts of Rockefeller Center then under construction.

He made murals for two public rooms at Radio City Music Hall; History of Cosmetics in the lower level Ladies's Lounge, and A Map of the World in the Gentleman's Smoking Room on the first mezzanine: the fully painted cartoon for the Africa portion is in the collection of Dr. Carl Weinberg of New York. Both murals remain in place in that Landmarked theater, in fact the Smoking Room and its mural were used as the location for a scene with Glenn Close and Jason Robards, Jr. in the 1994 movie The Paper. Gordon created decorative panels for the Grill of the Rainbow Room, a cocktail lounge atop the RCA Building, now the GE Building, were lost during one of many remodelings of that space. With repeal of Prohibition, a splendid show place, the International Casino, was opened across Times Square from the Astor Hotel, also but a memory. The Casino's ramped bar was backed with another Gordon mural, this one destroyed within three years of completion because of the Casino's bankruptcy. He created decorations for the main dining room of the Hotel New Yorker, also lost, but perhaps buried under layers of paint. Another, much earlier and important advertising commission of the period was the design of promotion pieces and posters for the 1932 Olympics Winter Games at Lake Placid. Gordon created the cover for the Marshall Field 1941 Christmas catalogue, a parade of the stores, houses and churches of Main Street. Until theatrical advertising agencies became creative organizations as well as the space buyers they had been, commercial printers, most notably Artcraft Lithograph and Printing Co. Inc and its predecessor, Golden Printing Service had been responsible for the art and design of posters and display cards for Broadway theater.

Witold Gordon was much used by Artcraft in the late 1920's, 30's and 40's. His work graced Theater Guild's Amphitryon 38 with the Lunts, Gilbert Miller's production Tovarich, the Norman Bel Geddes designed and staged Lysistrata and Witold was responsible for one of the theater's most recognized posters, OKLAHOMA! for which he created the bright yellow field scattered with stylized dancers and the title as a diagonal purple sash. All of this work, as printed, is part of the Theater Collection of the Museum of the City of New York, the Harvard Theater Collection, and the Library of Congress.

Vanity Fair published 15 small paintings of New York's indigenous art in July 1934 under the title New York Shops You Never See. By indigenous art Gordon meant the signs people paint, the bills they post and the at times curious ways they build and decorate their homes and workplaces. In 1936 Gordon started to design Christmas cards for the American Artists Group. By the time of his death, the Group had published several hundred of his designs. In the mid 1950's, Bloomingdale's selected him to create four successive annual exclusive Christmas card collections as elements in its 'trading up' to the 'up-scale' retailer it is today. The New York World's Fair of 1939-40 was a great showplace for Witold Gordon. He executed a mural on the bright blue waved wall of Edward Stone's Food Pavilion II. The Distiller's Building had mosaic fountains, another mural and a very stylish grains motif displayed over the entry, all Gordon designed. If this was not enough, he was called upon for murals in Arkansas' State Pavilion, New Zealand Pavilion and in one of the two House of Jewels. Under the rules for International Expositions as they were, all of this work was destroyed within six months of the Fair's closing. Gordon's work came to the attention of the Rich family of Atlanta, gaining him the commission to do murals for their store's main floor. In order to do the research he needed, Witold and his wife Marie spent several months driving through the South, Gordon recording the buildings and signs he saw along the way and credited by him as America's indigenous art. The murals were to have had a gala unveiling. The event was upstaged by the beginning of World War II. Marie, Witold's wife by this time, was very worried about the well being of her sister still living in Paris. To relieve anxiety, she started doing needlepoint; all of her work in this medium was done with very lyrical cartoons Gordon created for her alone.

The New Yorker commissioned Gordon to paint eight covers, published during 1944 to 1948. The covers were to be of the New York he saw so well. His sharp eye is revealed in the resulting covers, whether observing a pillow shop in the Lower East Side, a pastry shop in Little Italy, or the sign for a chiropodist's office over the Corn Exchange Bank on Sheridan Square. The original art for the April 6, 1946 issue now in the collection of the Museum of the City of New York depicts marine supply shops along Front Street.

After World War II ended, Gordon was called upon to do mural decorations for a projected Edward Stone designed hotel in Panama. A small revolution in that banana republic put an end to the syndicate planning the hotel, and the work was never executed. All that remains of the work, curiously reminiscent of Java and the Java illustrations in Adventures of Marco Polo is the cartoon for a needle point pillow and the pillow itself executed by Marie. In his 60's he slowed down on the assignment portion of his work. He continued to do Christmas cards for the American Artists Group, and was involved in an art oriented fabric design project with Reeves Lewenthal, at Associated American Artists. Theatrical posters continued to occupy some of his talent, but he began to devote almost full time to painting. Looking back over these notes, I find one word missing describing Gordon: ARTIST. I suppose it makes sense in light of the answer Witold Gordon gave me when I asked Exactly what kind of artist are you? His reply was Call me designer, muralist, reporter, cartographer, delineator, illustrator, painter, draftsman, renderer, or what you will. But artist? That is for them to say. He is represented in the collections of the Museum of the City of New York, Cooper Hewitt Museum of the Smithsonian Institution, and the Whaling Museum of Sag Harbor not to mention his place in the theater and private collections listed earlier. From the end of World War I Witold and Marie spent long summers away from New York, going to France each year until 1929, their first of several summers on Long Island's North Shore at Sea Cliff where I first met them. They spent a few World War II summers at Candlewood Lake sharing Alexander Calder's house boat with their very good friends Edgar and Louis Varese, prior to returning to Long Island. He and Marie took summer rentals on the South Fork in Sag Harbor, Wainscott, and Sagaponac every year. It was during the long summers, May to mid-October, that Marie and Witold did the living part of working for a living and he painted and sketched for his own pleasure. His subjects were all the things about him; the nasturtiums and petunias Marie planted, the flower arrangements she made for their home, the moss and greens they came across during their walks in the South Fork woods, the pebbles, shells and driftwood they found on the then empty beaches of Wainscott, Sagaponac and Georgica. He painted Victorian houses of Sag Harbor, the store fronts of Bridgehampton, and the shacks of Lazy Point which he lovingly called Lousy Point. All of this work was done before shells and driftwood became chic and the East End became the destination of New York's demimonde. After he developed heart problems in the early '60's, they moved from their Manhattan East 58th St. fifth floor walk up apartment which had also served as Witold's studio to a house in Sag Harbor. After a bout with cancer, and weeks of a dehumanizing stay, Witold Gordon died in Southampton Hospital in 1968. Submitted with the permission of Mr. Upton in April of 2006. - Shipping Info

-

All shipping arrangements and costs are the sole responsibility of the buyer. We are happy to assist in the transfer of merchandise to a shipper of your choice. Buyers should request a shipping quote prior to bidding. There are reliable shipping companies to use, and they include:

(1) The UPS Store:

Charlie Mosher

301 West Platt St

Tampa, FL 33606

(813) 251-9593

store3751@theupsstore.com

www.theupsstore.com/3751For a shipping quote, click the link below to get started on a quote OR to make payment for an existing quote: MyAuctionQuote.com/myers

(2) The UPS Store:

RayAnna Brodzinski

740 4th Street North

St. Petersburg, FL 33701

(727) 513-2400

shipping@store6886.com

www.theupsstore.com/6886(3) The UPS Store:

Rian Fehrman

5447 Haines Rd N,

St. Petersburg, FL 33714

(727) 528-7777

store6173@theuspsstore.com

www.theupsstorelocal.com/6173(4) Family Pak & Ship

Amel & Mohamed Hamda

2822 54th Avenue S.

St. Petersburg, FL 33712

727 865-2320

Raman@familypakandship.com

www.familypakandship.com(5) The UPS Store:

Gina Farnsworth

204 37th Ave N.

St Petersburg, FL 33704

(727) 822-5823

store3146@theupsstore.com

www.theupsstore.com/3146(6) The UPS Store:

200 2nd Ave South

St Petersburg, FL 33701

(727) 826-6075

store3248@theupsstore.com

www.theupsstore.com/3248(7) Craters & Freighters

(813) 889-9008

Fax (813) 884-8393

Tampa@cratersandfrighters.com

www.cratersandfreighterstampa.com (U.S. & International)(8) Orbit Professional Packing Crating

(888) 247-8540 or (727) 507-7447

lg@orbitppc.com

www.orbitppc.com (U.S. & International)LARGER ITEMS SHIPPING SUGGESTIONS

For items too large for standard shipping, such as furniture:

(1) Plycon - Furniture Transportation Specialists"

(954) 978-2000 (U.S. only)

lisa@plycongroup.com

www.plyconvanlines.com

You must submit a request on-line.(2) All Directions Moving

Specialist in moving furniture from FL to NY.

941-758-3800

alldirections@comcast.net

(3) Craters & Freighters

(813) 889-9008 or (877) 448-7447

Tampa@cratersandfreighters.com

(U.S. & International).(4) Westbrook Moving LLC

Makes regular trips up and down the east coast.

(404) 877-2870

westbrookdeliveries@gmail.com(5) Eastern Express

Owner Jeff Bills makes regular trips up and down the east coast.

(843) 557-6633

jb101263@yahoo.com(6) Can Ship US

Owner makes trips from Florida to Canada

Steve Fleury (905) 301-4866

canshipus@gmail.comThere are many other local and national shippers available in our area that we can refer you to. We are not responsible for any delays on the part of this third party shipper, should there be any. We recommend shipping all items insured. Should any damage occur to items transported by a third party, we are not held responsible. In the event that an item is approved for a return, shipping is not refundable.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB