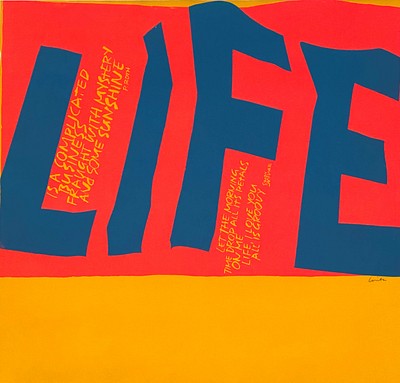

Sister Mary (1918-1986) signed Corita Kent Print

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $10 |

| $100 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,500 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $15,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Apr 30, 2023

Fine Art Auction - 35th Anniversary Myers Antiques auctions@myersfineart.com

- Lot Description

Sister Mary Corita Kent (American, 1918-1986) Screenprint. Title - No One Walks Waters. Original 1965 color serigraph screenprint on paper. Titled - No One Walks Waters. Transcribed text: Isn't that Jesus though the only God-love we know is human love.” This 1965 original serigraph print is identified in the archive as number 65-08. Original labeled Kulicke New York masonite and plexiglas frame. The label is inscribed in pencil, Reals Studio for the artist Nancy Ann Reals Perl Benderoth (1933-2018). The work is from her estate. Signed in pencil - Corita, middle right. Measures 29 inches high, 35 inches wide. In good condition.

From AskArt: Sister Mary Corita Kent, once the nation's best-known nun, won fame as a serigraph artist. Her bright, colorful silk-screen prints were the rage of the 1960s. She designed the United States' first "Love" postage stamp. Mary Corita Kent was born in Fort Dodge, Iowa in 1918, then moved with her family to Vancouver, British Columbia, in 1920. Two years later they moved to Los Angeles, where she grew up. She joined the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary there in 1938. She received her bachelor's degree from Immaculate Heart College in 1941, followed by a master's in art history 10 years later from the University of Southern California.

Popularly known as "Sister Mary Corita," she turned to the silk-screen process in 1950. Her large compositions combine quotations, often from the Bible or modern poetry, with religious or secular images. During her career as an artist and teacher, Kent also designed greeting cards and book covers. She achieved fame in the early 1960s with her brightly colored silkscreen posters. Some of her work includes excerpts from the writings of Carl Jung, e.e. cummings and Rainer Maria Rilke. She began adding words to her designs because, she said, "I have been nuts about words and their shape since I was very young." Sister Mary Corita became one of our country's most celebrated artists and gained international fame through her creative, magical use of color and words. As a muralist, her critically acclaimed 40-foot mural for the Vatican Pavilion at the 1964 New York World's Fair also brought her worldwide attention. She taught at Immaculate Heart College in Los Angeles, the art department of which, under her creative direction, established itself as a center for the art of learning as well as the learning of art. Buckminster Fuller described his visit to the department as "among the most fundamentally inspiring experiences of my life." As a teacher, she was known as a challenger, a free-thinker, a celebrator, an encourager. She taught her students that one of the most important rules, when looking at art or watching films, was never to allow yourself to blink. One might miss something extremely valuable. And what the students cherished most about her competence as a teacher was that she always made eye-contact with each individual, giving herself to each charge entirely.

Perhaps becoming a celebrity came too soon for the nun. It was something she never asked to be, but she carried the burdens of stardom with grace, kindness, and loving warmth. She never was arrogant, and accepted the status because she believed it would help the College of the Immaculate Heart where she was teaching, and she thought it would be good for her community of Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary. Sister Corita became a symbol of the modern nun and was often the target of conservative Catholics, particularly when she turned to regular street dress in 1967. During the late Sixties, the Church, like the rest of the country, was going through changes which angered, threatened, and tormented many of the faithful. The art of Sister Mary Corita began to infuriate certain conservative church leaders. She was considered dangerous. Once she was accused of being a "guerilla with a paint brush"; guerilla meaning an enemy who used familiar images to make blatant statements. It is doubtful if this attack offended the artist. She was a resister, a quiet activist who knew her soul, and did what she could to make the world a better place in which to live. All of this took a toll on Corita and the entire community, who had chosen to experiment and make what were considered "drastic" changes. Even before this, Corita was plagued with an acute case of insomnia. Witnesses who knew her well testified that she would not sleep for three or four nights on end, and that it was evident with every step she took. She was exhausted by all she'd agreed to take upon herself, and was unable to "let go" of her duties "after hours." Father Daniel Berrigan said of her: "Corita was the guardian angel of the world. Therefore she was called to be sleepless. After 32 years as an Immaculate Heart of Mary Sister, she began to ponder a leave of absence, perhaps hoping to resurrect her drooping spirit. After her sabbatical, she informed the community that she would not return, and this literally broke the hearts of her Sisters, who loved her dearly. More than that, they needed her vitality. But Corita felt that she needed time for healing. Collectors and fans of Corita's works -- those eye-pleasing, colorful, impressive, inspirationally blatant messages -- would certainly think that the artist was a very happy person. This simply was never true. She, herself, often admitted that she was down more than up.

After more than 30 years as a nun, Kent returned to private life in December 1968, moving to Boston to devote herself to her art, and opening a gallery. For the next eighteen years Corita created over 50 commissions, in addition to over 400 new editions of serigraphs. Special projects included the landmark 150-foot rainbow painting on the Boston Gas Company's natural gas tank; numerous murals, billboards, book covers and book illustrations, logos, greeting cards, etc. In addition, she published nine books of her own. She also created complete editions of serigraphs for fundraising use by numerous organizations dedicated to peace and social justice. She won dozens of art prizes and saw her work hung in many of the world's major art museums. Critics praised her prints as joyful, exuberant, bold and radiant. Around 1977, the artist developed cancer, and though her doctor gave her only six months to live, she knew that she had major art pieces to accomplish before she died --nine years later. Corita passed away in 1986, bequeathing her remaining prints, as well as the copyrights to all her works, to support the good works of the Immaculate Heart Community.

The Corita collection was cared for and administrated by volunteers until 1997. The art of Sister Mary Corita is in the permanent collections of over 40 major museums including the Victoria and Albert Museum in London; Art Institute of Chicago, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City; Museum of Modern Art, New York City; Boston Museum of Fine Arts; National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; and Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris.

Obituary from EastHamptonStar: Feb. 21, 2018

Nancy Ann Reals Perl Benderoth, an artist, designer, and producer of a documentary film that was nominated for an Academy Award, died at her Jericho Road, East Hampton, house on Feb. 6. Her family, who were with her at the end, said the cause of death was cardiac arrest brought on by pneumonia. She was 84 and had been in declining health for several years. She was born to Barney Reals and the former Annabel Whitney in Brooklyn on April 26, 1933, and grew up in the gated community of Seagate, adjacent to Coney Island. A lifelong painter, she attended Cooper Union and the Art Students League, both in Manhattan. Locally, she studied at the Art Barge on Napeague with Victor D'Amico of the Museum of Modern Art. Ms. Perl also worked as an assistant to other artists and as a stylist for such well-known photographers as Bert Stern and Irving Penn. At one time, she had a career in advertising, working for Mary Wells Lawrence at Wells, Rich, and Greene. Her husband had been collaborating with James Baldwin on a dramatic production of the life of Malcolm X, which eventually became a film. It was was incomplete when Mr. Perl died, and Ms. Perl, a producer on the project, stepped in. Working with the editor of the film, Mick Benderoth, the film was completed, and was nominated for an Academy Award in 1972. Ms. Perl and Mr. Benderoth began collaborating both professionally and personally. They formed a film production company, called Benderoth-Perl, and were married on Christmas Eve in 1990. She and Arnold Perl, a playwright, screenwriter, and producer were married in 1956. A former member of the Communist Party, Mr. Perl had been blacklisted and sold television scripts through a front. Though not a member of the Communist Party, she shared many of her husband's political beliefs. They met in the world of theater through Bernard Gersten, co-founder along with Joseph Papp of the Public Theater in Manhattan. She was an informal consultant on costumes and props for the 1953 stage production of "Sholem Aleichem" which her husband wrote. Mr. Perl also wrote "Tevya and His Daughters,” a basis for "Fiddler on the Roof.” In the early 1960s, the Perl family began summering in East Hampton. They were attracted by the many artists and writers and found many kindred spirits here. The family rented a house on Jericho Road for the summer of 1964, with the understanding that the rent could be applied toward a purchase price. They bought it for $36,000. A few years later, the couple also purchased a townhouse on East 18th Street in Manhattan. East Hampton became the center of their family's life, however, said Sarah Perl, one of the couple's daughters, and enjoyed living year round here. They were not religious and celebrated both Jewish culture and heritage as well as Christmas. Ms. Perl said yesterday that when the family spent a Christmas away from Jericho Road, in a house without a fireplace, she asked her mother how Santa would get in. Don't worry, was the answer, "I will let him in.” Ms. Perl Benderoth loved spending long days at Georgica Beach or Louse Point, going in the morning and staying until sunset. Her daughter said her mother would frequently take a black skillet and a stick of butter to Louse Point, where they would seine for and fry minnows. She would often stuff plums into the bottom of an ice-packed carrier. "You would stick your arm in up to your elbow, and pull them out,” Ms. Perl recalled. Her mother opened the Boutique at Enrico Caruso at 110 East 55th Street in Manhattan in 1965, where, her daughter said "she sold 'the best of everything,' including Viennese pastries made by her 70-year-old mother in a tiny kitchen in the Stuyvesant Town apartment complex.” - Shipping Info

-

All shipping arrangements and costs are the sole responsibility of the buyer. We are happy to assist in the transfer of merchandise to a shipper of your choice. Buyers should request a shipping quote prior to bidding. There are reliable shipping companies to use, and they include:

(1) The UPS Store:

Charlie Mosher

301 West Platt St

Tampa, FL 33606

(813) 251-9593

store3751@theupsstore.com

www.theupsstore.com/3751For a shipping quote, click the link below to get started on a quote OR to make payment for an existing quote: MyAuctionQuote.com/myers

(2) The UPS Store:

RayAnna Brodzinski

740 4th Street North

St. Petersburg, FL 33701

(727) 513-2400

shipping@store6886.com

www.theupsstore.com/6886(3) The UPS Store:

Rian Fehrman

5447 Haines Rd N,

St. Petersburg, FL 33714

(727) 528-7777

store6173@theuspsstore.com

www.theupsstorelocal.com/6173(4) Family Pak & Ship

Amel & Mohamed Hamda

2822 54th Avenue S.

St. Petersburg, FL 33712

727 865-2320

Raman@familypakandship.com

www.familypakandship.com(5) The UPS Store:

Gina Farnsworth

204 37th Ave N.

St Petersburg, FL 33704

(727) 822-5823

store3146@theupsstore.com

www.theupsstore.com/3146(6) The UPS Store:

200 2nd Ave South

St Petersburg, FL 33701

(727) 826-6075

store3248@theupsstore.com

www.theupsstore.com/3248(7) Craters & Freighters

(813) 889-9008

Fax (813) 884-8393

Tampa@cratersandfrighters.com

www.cratersandfreighterstampa.com (U.S. & International)(8) Orbit Professional Packing Crating

(888) 247-8540 or (727) 507-7447

lg@orbitppc.com

www.orbitppc.com (U.S. & International)LARGER ITEMS SHIPPING SUGGESTIONS

For items too large for standard shipping, such as furniture:

(1) Plycon - Furniture Transportation Specialists"

(954) 978-2000 (U.S. only)

lisa@plycongroup.com

www.plyconvanlines.com

You must submit a request on-line.(2) All Directions Moving

Specialist in moving furniture from FL to NY.

941-758-3800

alldirections@comcast.net

(3) Craters & Freighters

(813) 889-9008 or (877) 448-7447

Tampa@cratersandfreighters.com

(U.S. & International).(4) Westbrook Moving LLC

Makes regular trips up and down the east coast.

(404) 877-2870

westbrookdeliveries@gmail.com(5) Eastern Express

Owner Jeff Bills makes regular trips up and down the east coast.

(843) 557-6633

jb101263@yahoo.com(6) Can Ship US

Owner makes trips from Florida to Canada

Steve Fleury (905) 301-4866

canshipus@gmail.comThere are many other local and national shippers available in our area that we can refer you to. We are not responsible for any delays on the part of this third party shipper, should there be any. We recommend shipping all items insured. Should any damage occur to items transported by a third party, we are not held responsible. In the event that an item is approved for a return, shipping is not refundable.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB