Robert Butler (American, 1943-2014) Florida Highwayman Painting

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $10 |

| $100 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,500 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $15,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Apr 30, 2023

Fine Art Auction - 35th Anniversary Myers Antiques auctions@myersfineart.com

- Lot Description

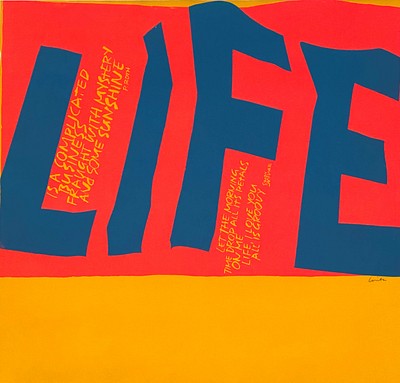

Robert Butler (American,1943-2014) Painting. Title - Marsh Scene with Egrets. Oil on Canvas. Signed lower right Robert Butler 77. Inscribed on the back of the stretcher in pencil, Demonstration, Brandon, Fla. November 10, 1977 Robert Butler. Measures 16 inches high, 20 inches wide. Frame measures 25 inches high, 28 inches wide. Florida highwaymen artist. In good condition.

Robert Butler was originally an Okeechobee, Florida, artist who painted apart from the rest of the Highwaymen. He was tall, good-looking, well dressed, and charismatic. Jeff Klinkenberg, who writes for the St. Petersburg Times, interviewed Robert several times before he died. Much of what we know about the artist and his work can be taken from his writings as well as a 2012 book Butler published with Sheila R. Munoz titled Highwaymen Artists: An Untold Truth. Robert was born in Baxley, Georgia, a small timber and farming town. He moved to Okeechobee with his mother, Annie Tolifer Butler, when he was four years old. They had very little money when Robert was growing up. He spent much of his time exploring nature and became well acquainted with the Everglades and Lake Okeechobee. As a boy, he hunted rabbits, hogs, and deer. Reflecting on these activities, Robert recognized the similarity in the two activities; both artists and hunters need to pay attention to their environment. As a young child, he learned to read the land. Robert graduated from a segregated high school, and because his employment choices were limited, he mowed lawns and did maintenance work at dairies. When one of his lawn clients saw his drawings, he gave Robert an $11 oil painting to encourage his talent. This same customer also helped him get a job as a hospital orderly. Working in the hospital as the sun went down, Robert would look out the window and have a strong desire to paint the sunset. His hospital position gave him proximity to potential customers and he was able to sell work to doctors and other hospital personnel. One discerning doctor commissioned him to paint a prized Appaloosa horse. Robert had to repaint the picture forty times, a lesson that taught him patience and the importance of detail. To give more visibility to his art, Robert set up his easel by a mall in the center of town. Word spread and Butler’s sales increased. When an Okeechobee librarian saw his work, she paid a $25 fee for him to take a correspondence art class. Remarking on the area's reputation as a racist town, art promoter and early Highwaymen collector Jim Fitch explained to Klinkenberg, Okeechobee, some folk will tell you, might be the heart of Florida's redneck belt. But many who helped Robert along the way were white. In fact, Robert claimed he didn't remember racism in the 1950s and 60s, or maybe, he said, he didn't want to remember it. In spite of the racial tensions of the times, the town helped him succeed. His best selling works were turkey paintings, which were particularly prized by hunters. When a landscape didn't sell, he'd quickly paint a turkey in it and it would readily please a customer.In 1969, Don Herold, then Director of the Polk Museum of Art, saw Robert’s work and offered him a show. After the 1970 exhibition at the museum, his sales increased substantially. Robert Butler was on his way to becoming an established, marketable artist. Robert credits his mother, who worked three jobs, with his strong work ethic. She picked tomatoes, waited tables in restaurants, and cleaned hotel rooms to make ends meet. Butler told Jeff Klinkenberg She was one of those people who believed you could accomplish anything if you worked hard enough. In 1995, a white businessman who believed in her work ethic, loaned her $5,000. She invested in a boarding house and with the profits she purchased a restaurant. She bought cast-off lumber from demolition sites at low prices and used it to build other boarding houses. Determined to save money where she could, she laid the foundations herself. Once Robert's work was selling well, he quit his job as an orderly. He knew he had to take a risk. He explained to Klinkenberg, I was swimming in this fantastic psychological soup at the time; I came from this poor background and yet this door was opening wide for me, to this universe that could be explored forever. I wanted to paint as much as I could and never looked back. Butler married and eventually had nine children. Keenly aware of his responsibility as a father and a husband, he knew he had to sell his paintings if he was going to support his family. He explained, I'd put the paintings in my station wagon and $10 in my pocket for gas. It was a one-way ticket. I had to sell some paintings to get back (home). His early paintings were done quickly. He took to the roadways in 1968 and sold his paintings for around $35, much like the other Highwaymen. He stayed on the road until every landscape was sold. He was a smart salesman, often targeting ranchers who had an affinity for the land. He'd ask for referrals, remembering how well that system of selling worked at the hospital. If he didn't have just the right painting for someone, he'd make a sketch and return later with a finished landscape that might be more to the Butler had a longtime friendship with Jim Fitch, the man who later named the Highwaymen. Their friendship began in Okeechobee and they bonded over their love of the Florida landscape and the Bible. Jim helped Robert in the early years by building frames for his artwork and giving him marketing advice. Jim purchased his first painting from Robert in 1967. He sold Butler's work in his Okeechobee arts and crafts store and gallery and later in his Sebring art gallery. Robert also taught classes in Jim's Sebring classroom that was part of the gallery. Butler's lifestyle changed as his paintings improved and his reputation grew. In 1965 he drove a beat up Oldsmobile Catalina 50,000 miles a year. When it broke down once in Haines City, he paid for a new rear wheel bearing with a turkey painting. By 1995 he was one of the best-known landscape painters in Florida and was driving a prized 1972 four-wheel drive Chevy Suburban. He spent less time on the road as he had more opportunities to sell his work. When he traveled, he could be gone for days. He'd often stop to sketch a striking landscape or study something particular that he wanted to remember and incorporate into his work. His goal was to document correctly. Sometimes when he'd stop at a motel for the night, he would paint what inspired him on the trip. The quiet of the motel space was appealing. He told Klinkenberg: Creativity, by its very nature, is about exploration. You have to have at least the illusion of being free to explore your ideas. For me, that means going to a place where I can shut out all distractions. Nobody can call me. I don't watch TV and I don't listen to the radio. I paint. Eventually, Butler started making prints and advertising in outdoor magazines. He moved his family to Lakeland and opened a gallery. At first, money was the primary motivation for his painting, especially as his family grew. He explained, Listen, there's nothing in the world like nine children to get you up on your feet and out the door painting and selling. But as success came, and he was sometimes making $7,500 for a painting, he concentrated more on the quality of his work. Still, he traveled frequently and lamented the time away from his family. He wrote in his book, A special tribute goes to my wife Dorothy and the rest of my family for the support they gave under sometimes difficult circumstances. Many are the hours, days, and sometimes weeks they have suffered from the lack of my presence amid the family circle. In the summer of 1993, Butler took a cultural exchange trip to Africa hoping to establish a connection with his ancestors. A hired tour guide took him to Tanzania. Here, he painted in a small Masai village in the high plains. He painted ostriches, stone huts, the village people, and the dry and dusty plains of the area. The trip changed the way he saw the world, and especially the way he experienced light. In February 2008, a fire destroyed more than 200 of his early paintings. Luckily, he had photographs of many of these works, which he was able to reproduce in his book. In this publication, he gives credit to other Florida landscapers who gave him inspiration. He also comments on the Civil Rights Movement and the Highwaymen's paintings: Not created to replicate the turmoil of our time in protest, our art recorded the things positively affecting our humanity and reflects only the best of our world….While it is clear that living amid the racially charged environment of the Civil Rights Era theoretically challenged our dreams of deriving wealth and prosperity from our art, once on the streets we were thrilled to discover that the love of art transcended racial discord. Robert Butler's life was filled with a deep love for Florida's wilderness. On March 19, 2014, Robert Butler died in Lakeland from complications related to his thirty years as a diabetic. His marriage to Dorothy lasted over fifty years. Eight of his nine children paint or painted at some time during their lives. It is best to understand Robert's relationship to the land in his own words. In 2012, he wrote: Strikingly beautiful, the Kissimmee River was my source of constant inspiration, just as the beaches were for the coastal Highwaymen during all the years that I lived in the region. Its windswept, black waters sparkled at midday, evoking visions of timeless vistas where droves of birds sailed the warm winds above. I would often take long walks before or after work and fish along the levee that contained the river after the early 1960s. My favorite time was at daybreak when I would imagine myself suspended in a Salvador Dali world where huge flights of white egrets silently passed overhead as if steered to some mysterious destination known only to nature. - Shipping Info

-

All shipping arrangements and costs are the sole responsibility of the buyer. We are happy to assist in the transfer of merchandise to a shipper of your choice. Buyers should request a shipping quote prior to bidding. There are reliable shipping companies to use, and they include:

(1) The UPS Store:

Charlie Mosher

301 West Platt St

Tampa, FL 33606

(813) 251-9593

store3751@theupsstore.com

www.theupsstore.com/3751For a shipping quote, click the link below to get started on a quote OR to make payment for an existing quote: MyAuctionQuote.com/myers

(2) The UPS Store:

RayAnna Brodzinski

740 4th Street North

St. Petersburg, FL 33701

(727) 513-2400

shipping@store6886.com

www.theupsstore.com/6886(3) The UPS Store:

Rian Fehrman

5447 Haines Rd N,

St. Petersburg, FL 33714

(727) 528-7777

store6173@theuspsstore.com

www.theupsstorelocal.com/6173(4) Family Pak & Ship

Amel & Mohamed Hamda

2822 54th Avenue S.

St. Petersburg, FL 33712

727 865-2320

Raman@familypakandship.com

www.familypakandship.com(5) The UPS Store:

Gina Farnsworth

204 37th Ave N.

St Petersburg, FL 33704

(727) 822-5823

store3146@theupsstore.com

www.theupsstore.com/3146(6) The UPS Store:

200 2nd Ave South

St Petersburg, FL 33701

(727) 826-6075

store3248@theupsstore.com

www.theupsstore.com/3248(7) Craters & Freighters

(813) 889-9008

Fax (813) 884-8393

Tampa@cratersandfrighters.com

www.cratersandfreighterstampa.com (U.S. & International)(8) Orbit Professional Packing Crating

(888) 247-8540 or (727) 507-7447

lg@orbitppc.com

www.orbitppc.com (U.S. & International)LARGER ITEMS SHIPPING SUGGESTIONS

For items too large for standard shipping, such as furniture:

(1) Plycon - Furniture Transportation Specialists"

(954) 978-2000 (U.S. only)

lisa@plycongroup.com

www.plyconvanlines.com

You must submit a request on-line.(2) All Directions Moving

Specialist in moving furniture from FL to NY.

941-758-3800

alldirections@comcast.net

(3) Craters & Freighters

(813) 889-9008 or (877) 448-7447

Tampa@cratersandfreighters.com

(U.S. & International).(4) Westbrook Moving LLC

Makes regular trips up and down the east coast.

(404) 877-2870

westbrookdeliveries@gmail.com(5) Eastern Express

Owner Jeff Bills makes regular trips up and down the east coast.

(843) 557-6633

jb101263@yahoo.com(6) Can Ship US

Owner makes trips from Florida to Canada

Steve Fleury (905) 301-4866

canshipus@gmail.comThere are many other local and national shippers available in our area that we can refer you to. We are not responsible for any delays on the part of this third party shipper, should there be any. We recommend shipping all items insured. Should any damage occur to items transported by a third party, we are not held responsible. In the event that an item is approved for a return, shipping is not refundable.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB