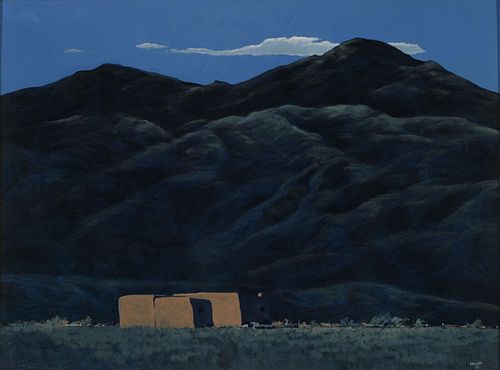

Phil Epp (American, 1946-) Moonlight Oil Painting

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $10 |

| $100 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,500 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $15,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Apr 30, 2023

Fine Art Auction - 35th Anniversary Myers Antiques auctions@myersfineart.com

- Lot Description

Phil Epp (American, 1946- ) Painting. Title - Moonlight Landscape. Oil on masonite painting. Signed lower right Phil Epp. Also signed by Phil Epp and titled Moonlight on reverse. Painting measures 18 inches high, 24 inches wide. Frame measures 23 inches high, 29 inches wide. In good condition.

From Askart.com: The following information is from an interview by John D. Thiesen and Ami Regier, published in Mennonite Life, December 2003. Born in Henderson, Nebraska, on August 28, 1946, Phil Epp became an artist, graduated from Bethel College in 1972, and taught art in the Newton public school system for 30 years, retiring in May 2003. In the evolution of his art practice, his paintings have become widely known; his work is now available in galleries in Santa Fe and Taos, New Mexico; Chicago, Illinois; Kansas City, Missouri; and Tubac, Arizona; and in municipal settings with several recent large-scale, sculptural, collaborative public art projects.

This interview was conducted August 27, 2003, at Epp's studio east of Newton, Kansas, a structure added three years ago to the home he shares with his wife, art teacher Karen Epp, two children Kate and Justin (when they were younger), three horses, and a dog. The home and studio are set on 16 acres, and Phil and Karen designed it in relation to the Spanish-influenced architecture of the American Southwest.

Phil Epp noted that he researched Kansas art history and became more influenced by the realists later in his career, and thus identifies them in this interview as influences in the last few years of his work. His earlier influences include a wide range of artists, including the minimalists and color field artists who developed as dimensions of abstract expressionism. For example, the color fields of Mark Rothko paintings offer a precedent for the abstract quality of landscape and giant color field of the sky in Phil Epp's paintings. Phil cited two contemporary artists who have been important influences: Richard Serra (minimalist American sculptor) and James Turrell (minimalist, American, Quaker installation artist). Turrell's work shares a focus in what he describes as skyscapes with Phil Epp's compositions; his work on the geography and sky space of Roden Crater can be viewed online. In addition, Robert Regier continues to be an influential colleague.

Information from the interview includes the following comments by the artist: As far as art is concerned, my parents were encouraging of my drawing. They also had an aesthetic sense about the land that I think was important. The wide-openness of the landscape and my parents' interest in the aesthetics of the weather was really significant…There were individuals in the community who were very supportive. Basically we're talking Mennonites here, so we're talking music, and I didn't fit that.

After graduating from Bethel College in 1972, I went looking for a job as a teacher and stayed with that for 30 some years. Yes, I was always an art teacher. Then, a lot of times the question came up, should I get my master's? I always kind of balked. First of all, I didn't want to. I didn't want to go to school. I didn't want to spend the time or money or energy. Now, this being my first year of retirement, I've thought oftentimes that people plan only for their careers, but they don't plan beyond their careers. So I'm really kind of glad I didn't get my master's. That energy went into art. Working on art took the energy that I had. . . . I didn't bring my work into the classroom for years. When the work started selling, I also became worried about conflict of interest. For instance, what if I did a painting demonstration in class, and then later sold it? I thought I could get in trouble with it some way or another, so I kept them pretty separate.

Of Blue Sky, Public art project in Newton, Kansas: Most of the projects have been cooperative projects with other artists, and that has been a new experience. So those two things, working with public art, and working cooperatively with other artists, have developed in the last three-four years. I think part of that came about because of my interest in sculpture. Here's the idea: my interest in sky as open space or openness. It's you with the natural landscape, just the juxtaposition of the artificial and the natural, when the artificial represents the natural. . . .You had asked how the projects came about. Terry Corbett (ceramic tile artist, Wichita, KS) and I had done a ceramic tile wall mural in El Dorado, KS, about five years ago. (on Main Street just north of the Coutts Art Museum.) And then we did a small mural together here on Main Street, (above the Scrapbook Gallery at 504 N. Main) and Terry Corbett has been involved in most of these projects. We worked together on most of these things, and they (the owners) determined what they wanted.

Of promoting public art: That's one of the lessons: have a lot of coffee. I think the artist has to be the aggressor, because art isn't something that people necessarily prioritize. So I have a somewhat aggressive attitude, and the galleries I've dealt with have required an aggressive attitude. Survival: You can't be passive in art and survive. Subtlety doesn't cut it as far as art is concerned. My approach is that I develop a model, and show a potential audience what I want to do, and if it doesn't happen, I still have this wonderful idea that I developed. And it doesn't really matter whether they accept it or they don't; we went through the process of the model and anr idea, and we're making art the way we hoped to make it. And so I got on that kick: we made the model. We proposed it to a committee, and there were some helpful people who wanted to see it come about. Blue Sky project was initially tied to the baseball diamond on First Street. That was an interesting phenomena: the sports complex was eventually cut, but the art project was pretty much committed, so the foundation had changed. That's when we got the place over there (the current site on Kansas Avenue by Centennial Park). That was a long process.

Of Blue Sky Project: some contact with the Sand Creek restoration project by the corps of engineers developed. There was an archeologist who came down from Arizona, and I got to know him, and he would take me around. He was intrigued by the (current) location; he said there were four distinct civilizations that lived in the area. Native Americans, 500 years ago: it was a real hub. Then it was the initial landfill 100 years ago (for Newton). The third stage was the landfill 30 years ago, covered, and then, fourth, the current culture and use. Then he was really intrigued with how this is the perfect spot to show what happens with rivers. First, trade and commerce and so on, and then it turned into this waste area-dumping ground, then the recreational area reclaims the waste area.

I'm on the side of public art, plain and simple. I think it's important. I think that a lot of people can get some use out of it. A lot of it (its value) isn't immediate. Down the road, people will see it as pretty neat.---Also did cloud motif city direction signs for Newton Attractions. And mural above Scrapbook Gallery that is a train pulled by the Santa Fe Chief going across the panoramic landscape and public art project in Olathe, Kansas, Reflective Spaces at the R.R. Osborn Plaza. Large scale vertical slabs of land dominated by blue sky with white clouds. I didn't want to make a flat surface, in a three-dimensional park, like a billboard with pictures on it. Sitting in a meeting, I had an idea to separate these things in this way. It will be more of a landscape, an Olathe landscape . . . The thing that makes it interesting to me is that the pieces bisect the landscape at angles; they aren't going to be flat. Light will hit them different ways at different times, with stones and sky and stuff in between the images. With the base it will be 17-18 feet tall.

Of his art and his Mennonite Religion: I'm not too interested in hanging out with art-friendly Mennonites. This is why I like the regionalists. I don't expect to go to church and talk about art. I'm not even a fan of people performing in church. I don't even necessarily think it's appropriate for people to perform in church. I like the people, and I like the church, and I have a lot of respect for them, and I'm not sure why we don't go. We'll probably go back again sometime soon.

Answer to question of Are you a Plains artist or a Southwestern artist? Are you a Nebraska or Kansas artist? I grew up overlooking a big basin, a low land area where water would collect. We had a quarter section pasture. Prairie, actually: it was different from a pasture. No buildings for a few miles. Pretty open space; I always liked the plains. I can see that this painting does look a bit more like eastern New Mexico; most of the time I don't really identify them as belonging to a certain place. They develop as their own location. Usually they have a little mix of New Mexico and Kansas in them. All the realists influenced me, among other influences: Benton, Curry. And there was some overlap: Ward Lockwood was a New Mexico artist who was born in Kansas. He was a significant New Mexico artist. He came to Kansas, started abstraction, from a pretty realistic starting point. He has Kansas roots. Quite a few of the New Mexico artists have Kansas roots. Part of that has to do with the Santa Fe railroad and just the intrigue with the Southwest. But there's quite a connection between the Southwest and Kansas art. Many of these were swallowed up by modernism. Others adapted and updated their realism to modernism.

Of composition of his landscapes relative to low horizon lines and color gradations in sky, Phil Epp said: Those aspects evolved and became refined over the years. Depth is created by darker color at the top of the composition. When teaching art, one is always teaching perspective. That affected my work. The low horizon gets you kind of looking up. Low horizon is something that, talking about Kansas and Midwestern painters, influenced me in the 1970s. I remember Keith Jacobshagen, who I met once or twice. He was an instructor at Nebraska, and was one of the first artists that I remember shoving the horizon line way down. I remember going to one of his shows at Reuben Saunders Gallery in Wichita and thinking wow, that's pretty neat. And so, I think that's where I started shoving the landscape down. He was a part of a school of landscape painters at the time, and he did that. It worked for me to shove the horizon line down quite a ways because it became more about the sky than about land. - Shipping Info

-

All shipping arrangements and costs are the sole responsibility of the buyer. We are happy to assist in the transfer of merchandise to a shipper of your choice. Buyers should request a shipping quote prior to bidding. There are reliable shipping companies to use, and they include:

(1) The UPS Store:

Charlie Mosher

301 West Platt St

Tampa, FL 33606

(813) 251-9593

store3751@theupsstore.com

www.theupsstore.com/3751For a shipping quote, click the link below to get started on a quote OR to make payment for an existing quote: MyAuctionQuote.com/myers

(2) The UPS Store:

RayAnna Brodzinski

740 4th Street North

St. Petersburg, FL 33701

(727) 513-2400

shipping@store6886.com

www.theupsstore.com/6886(3) The UPS Store:

Rian Fehrman

5447 Haines Rd N,

St. Petersburg, FL 33714

(727) 528-7777

store6173@theuspsstore.com

www.theupsstorelocal.com/6173(4) Family Pak & Ship

Amel & Mohamed Hamda

2822 54th Avenue S.

St. Petersburg, FL 33712

727 865-2320

Raman@familypakandship.com

www.familypakandship.com(5) The UPS Store:

Gina Farnsworth

204 37th Ave N.

St Petersburg, FL 33704

(727) 822-5823

store3146@theupsstore.com

www.theupsstore.com/3146(6) The UPS Store:

200 2nd Ave South

St Petersburg, FL 33701

(727) 826-6075

store3248@theupsstore.com

www.theupsstore.com/3248(7) Craters & Freighters

(813) 889-9008

Fax (813) 884-8393

Tampa@cratersandfrighters.com

www.cratersandfreighterstampa.com (U.S. & International)(8) Orbit Professional Packing Crating

(888) 247-8540 or (727) 507-7447

lg@orbitppc.com

www.orbitppc.com (U.S. & International)LARGER ITEMS SHIPPING SUGGESTIONS

For items too large for standard shipping, such as furniture:

(1) Plycon - Furniture Transportation Specialists"

(954) 978-2000 (U.S. only)

lisa@plycongroup.com

www.plyconvanlines.com

You must submit a request on-line.(2) All Directions Moving

Specialist in moving furniture from FL to NY.

941-758-3800

alldirections@comcast.net

(3) Craters & Freighters

(813) 889-9008 or (877) 448-7447

Tampa@cratersandfreighters.com

(U.S. & International).(4) Westbrook Moving LLC

Makes regular trips up and down the east coast.

(404) 877-2870

westbrookdeliveries@gmail.com(5) Eastern Express

Owner Jeff Bills makes regular trips up and down the east coast.

(843) 557-6633

jb101263@yahoo.com(6) Can Ship US

Owner makes trips from Florida to Canada

Steve Fleury (905) 301-4866

canshipus@gmail.comThere are many other local and national shippers available in our area that we can refer you to. We are not responsible for any delays on the part of this third party shipper, should there be any. We recommend shipping all items insured. Should any damage occur to items transported by a third party, we are not held responsible. In the event that an item is approved for a return, shipping is not refundable.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB