Paul Thek (American, 1933-1988) Cityscape Painting

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $10 |

| $100 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,500 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $15,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Apr 30, 2023

Fine Art Auction - 35th Anniversary Myers Antiques auctions@myersfineart.com

- Lot Description

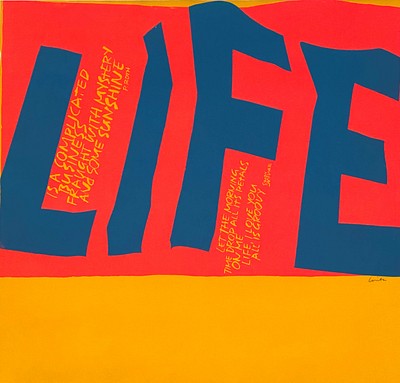

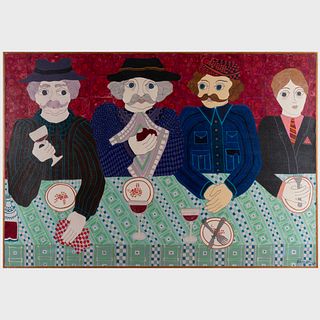

Paul Thek (American, 1933-1988) Painting. Title - Cityscape with Rooftops. Watercolor and gouache painting on paper. Signed lower right Thek ‘79. Sight size of the painting measures 16.7 inches high, 21.8 inches wide. Frame measures 25.75 inches high, 31 inches wide. In good condition, tape hinged at top, not laid down. From the Water Mill, NY estate on Long Island of Academy Award nominated film director Anthony (Tony) Harvey (1930-2017).

From Askart.com: The following review, by Holland Cotter, is from The New York Times, October 21, 2010 Paul Thek (1933-1988), the subject of a ragged, moving and much-anticipated retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art, was only 54 when he died of AIDS in 1988. But by then he had already slipped through the cracks of art history. Or rather he had fallen into one of the deep trenches that divide that history into artificial islands with names like Pop and Minimalism. Thek came to art with so much going for him — talent, looks, energy and imaginative peculiarity — that for a decade or so he was an island unto himself, an archipelago even. In the early 1960s, when everyone else in New York was into hands-off fabrication and Benday dots, he was modeling hyper-realistic images of meat, raw and bleeding, from beeswax. Gross and funny, they had people buzzing. Then in 1967 Thek abruptly left for Europe and radically changed his art. Instead of sculpture, he created immense, collaborative, ephemeral environments from throwaway stuff: newspapers, candles, flowers, onions, eggs, sand. When their time was up, these works went into the rubbish bin. Thek, with his long blond hair and pied-piper charm, was a big success in Europe. Museums threw open their doors. He stayed for nine years. In 1976 he returned to New York and had a nasty shock. Almost no one here remembered the work he had done in the 1960s, or knew what he had been up to in Europe in the years since, or cared about what he was doing in the present. He had been away too long. The '60s were over. He had a few Manhattan gallery shows and a museum solo in Philadelphia, but people stayed away. Depressed and angry, he painted quick, small pictures in his East Village walk-up, smoked a lot of pot, cruised local parks and kept an obsessively confessional diary. To support himself, he bagged groceries in a supermarket, washed hospital floors. Europe was far, far away; 1980s New York, with its bottomless cash and gated art world, far too close. His memorial service at St. Mark's Church in-the-Bowery was a fair gauge of his stature. The church wasn't packed, but the eulogists — Robert Wilson, Susan Sontag — were stars. Sontag, an old friend, had dedicated her breakthrough book, Against Interpretation, to Thek in 1966. In 1989 she would dedicate another, AIDS and Its Metaphors, to his memory. Since his death Thek's reputation, always high in Europe, has grown in the United States. In the 1990s, a time of identity politics and AIDS, there were Thek shows, articles, books. In the early 2000s, with young artists interested in the quirky and the personal in art, his influence was strong and was acknowledged by older figures like Robert Gober and Mike Kelley. Now, finally, if with slightly behind-the-beat timing, comes Paul Thek: Diver, a Retrospective, at the Whitney. What do we find? Less than hoped for, perhaps, but more than anticipated: solid concentrations of the early sculptures and the later paintings; mere scraps of the great environments that came between. Do they add up to a career survey? With the help of documentary photographs, an accessible catalog, and an application of Thek's own definition of faith — Believing is seeing — they do. The beginnings of that career were ordinary. The artist was born George Joseph Thek — the Paul came later — to a middle-class Brooklyn family of German and Irish descent. His parents were Roman Catholic; the first art he saw was in churches. His connection to religion remained deep, and deeply conflicted. He studied painting at Cooper Union in the 1950s and at that time met Sontag, Eva Hesse and the photographer Peter Hujar. Thek was alert to the new art and artists around him: Jasper Johns, Allan Kaprow, Claes Oldenburg and Robert Rauschenberg; later Joseph Beuys and Arte Povera. He readily spoke of their impact on him. He made a momentous first trip to Europe in 1962. He cried in front of van Goghs in Amsterdam, stood drop-jawed before Michelangelo in Rome. The major event, though, came when he and Hujar, traveling as lovers, stumbled on Capuchin catacombs in Sicily: caves packed with corpses encased in glass coffins and propped against walls. Hujar took photographs; Thek got ideas for a new kind of art. What resulted were the sculptures of meat and amputated limbs, which Thek sealed into sleek Formica and plexiglass containers, and in one instance into an Andy Warhol Brillo box turned on its side. Collectively called Technological Reliquaries, they were clearly sendups of Minimalism's industrial machismo and Pop's complicit consumerism — though at a time when a brutal war was building in Southeast Asia, they also hinted at larger politics. The culminating work from this period, The Tomb — Death of a Hippie, became Thek's most famous, and infamous, piece: it consisted of a full-size cast of his body laid out as if dead, surrounded by sacramental bowls and possible drug paraphernalia, inside a pink wooden pyramid. Readings of the image have been endless: it's a symbol of the putrefying ideals of the 1960s; it's a narcissistic joke. Whatever its meaning, the piece now exists only in photographs.

Obituary from NY Times - Dec. 13, 2017: Anthony Harvey, Lion in Winter - Director and Kubrick Editor, Dies at 87.

It might have gone down as the most ridiculous scene in the most audacious film that Anthony Harvey ever worked on, but at least as Mr. Harvey told the story, a momentous event in the real world kept it from the moviegoing public. It was an epic two minutes worth of pie throwing, and it was originally to be the ending of - Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, - Stanley Kubrick's dark satire of the nuclear age. Mr. Harvey, the editor on that movie, was pretty pleased with the way the chaotic scene had come out. It was a brilliant piece of work, he once said. Who knows? I certainly thought it was. But the movie, which was scheduled for release in January 1964, was to receive its press premiere in late November 1963, right when all sorts of plans were thrown into turmoil by the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. That ending, how it started, the George Scott character threw a custard pie to the Russian ambassador, and it missed and hit the president, Mr. Harvey told the film journalist Glenn Kenny in 2009. Columbia Pictures, he said, was very nervous about anything to show the president, any president in that state. As a result, the pie-throwing scene was scrapped. Others involved with the movie have over the years given different explanations for the changed ending, but in any case the airborne pies were replaced with the now familiar montage of nuclear explosions - set to Vera Lynn's rendition of the song We'll Meet Again, an unsettling ending instead of a slapstick one. Mr. Harvey would go on to become a director himself, teaming with Katharine Hepburn on several films, most notably The Lion in Winter (1968), for which he was nominated for an Oscar. He died on Nov. 23 at his home in Water Mill, on Long Island, at age 87. The Brockett Funeral Home confirmed the death. Mr. Harvey was born on June 3, 1930, in London. His father, Geoffrey Harrison, died when he was young, and after his mother, the former Dorothy Leon, remarried, he took the surname of his stepfather, Morris Harvey, an actor. He got an early taste of the movie business when he was cast in a small part in the 1945 film "Caesar and Cleopatra," which starred Claude Rains and Vivien Leigh, but his real entree came when he landed a job as an editor for the British filmmakers John and Roy Boulting. He learned the art of editing as it was done in predigital days, pasting countless film clips together by hand. He received his first film-editor credits in 1956, on a short called - On Such a Night and the feature Private's Progress, a war comedy. He was the editor on Kubrick's - Lolita in 1962, which led to the - Dr. Strangelove assignment, a difficult one that involved cutting between three concurrent story lines, one set in the war room of the American government. We had a huge kind of war room of our own in the cutting room, Mr. Harvey told Mr. Kenny, and we put up pieces of paper representing every sequence in different order. It was Kubrick, he said in a 1994 interview with The New York Times, who told Mr. Harvey that he was ready to direct. It was Kubrick, too, who gave him an important piece of advice: If an actor is giving a dazzling performance, hold on to that shot and resist the temptation to cut away to, for instance, the reactions of other characters in the scene. In 1966, Mr. Harvey directed - Dutchman, a short film based on a play by LeRoi Jones, who would become better known as Amiri Baraka. Peter O'Toole was impressed enough by that film that he recruited Mr. Harvey for - The Lion in Winter, in which Mr. O'Toole starred as Henry II opposite Katharine Hepburn as Eleanor of Aquitaine. Working with her is like going to Paris at the age of 17 and finding everything is the way you thought it would be, Mr. Harvey said. Hepburn won an Oscar for her performance, splitting the award with Barbra Streisand, who won for Funny Girl. Mr. Harvey also directed Hepburn in a well-regarded television adaptation of Tennessee William's - The Glass Menagerie in 1973. John J. O'Connor, reviewing that film in The Times, called it a special TV event, demanding attention. It won four Emmy Awards. But Mr. Harvey's output as a director was limited. His handful of theatrical releases included the comedy - They Might Be Giants in 1971, the drama Richard's Things in 1981 and another Hepburn vehicle, Grace Quigley, in 1985. That movie was poorly received, and Mr. Harvey retreated from film directing, returning only in 1994 for This Can't Be Love, a television movie starring Hepburn and Anthony Quinn. He retired to his Long Island home, which he had acquired three years earlier. He leaves no immediate survivors. Mr. Harvey was comfortable working in Hollywood but preferred life on the East Coast, where the film business was not quite so all-consuming. He told of once having surgery in a Los Angeles hospital. As I was coming to, he recalled, the anesthesiologist said, - I'm very anxious to get into movies. - Shipping Info

-

All shipping arrangements and costs are the sole responsibility of the buyer. We are happy to assist in the transfer of merchandise to a shipper of your choice. Buyers should request a shipping quote prior to bidding. There are reliable shipping companies to use, and they include:

(1) The UPS Store:

Charlie Mosher

301 West Platt St

Tampa, FL 33606

(813) 251-9593

store3751@theupsstore.com

www.theupsstore.com/3751For a shipping quote, click the link below to get started on a quote OR to make payment for an existing quote: MyAuctionQuote.com/myers

(2) The UPS Store:

RayAnna Brodzinski

740 4th Street North

St. Petersburg, FL 33701

(727) 513-2400

shipping@store6886.com

www.theupsstore.com/6886(3) The UPS Store:

Rian Fehrman

5447 Haines Rd N,

St. Petersburg, FL 33714

(727) 528-7777

store6173@theuspsstore.com

www.theupsstorelocal.com/6173(4) Family Pak & Ship

Amel & Mohamed Hamda

2822 54th Avenue S.

St. Petersburg, FL 33712

727 865-2320

Raman@familypakandship.com

www.familypakandship.com(5) The UPS Store:

Gina Farnsworth

204 37th Ave N.

St Petersburg, FL 33704

(727) 822-5823

store3146@theupsstore.com

www.theupsstore.com/3146(6) The UPS Store:

200 2nd Ave South

St Petersburg, FL 33701

(727) 826-6075

store3248@theupsstore.com

www.theupsstore.com/3248(7) Craters & Freighters

(813) 889-9008

Fax (813) 884-8393

Tampa@cratersandfrighters.com

www.cratersandfreighterstampa.com (U.S. & International)(8) Orbit Professional Packing Crating

(888) 247-8540 or (727) 507-7447

lg@orbitppc.com

www.orbitppc.com (U.S. & International)LARGER ITEMS SHIPPING SUGGESTIONS

For items too large for standard shipping, such as furniture:

(1) Plycon - Furniture Transportation Specialists"

(954) 978-2000 (U.S. only)

lisa@plycongroup.com

www.plyconvanlines.com

You must submit a request on-line.(2) All Directions Moving

Specialist in moving furniture from FL to NY.

941-758-3800

alldirections@comcast.net

(3) Craters & Freighters

(813) 889-9008 or (877) 448-7447

Tampa@cratersandfreighters.com

(U.S. & International).(4) Westbrook Moving LLC

Makes regular trips up and down the east coast.

(404) 877-2870

westbrookdeliveries@gmail.com(5) Eastern Express

Owner Jeff Bills makes regular trips up and down the east coast.

(843) 557-6633

jb101263@yahoo.com(6) Can Ship US

Owner makes trips from Florida to Canada

Steve Fleury (905) 301-4866

canshipus@gmail.comThere are many other local and national shippers available in our area that we can refer you to. We are not responsible for any delays on the part of this third party shipper, should there be any. We recommend shipping all items insured. Should any damage occur to items transported by a third party, we are not held responsible. In the event that an item is approved for a return, shipping is not refundable.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB