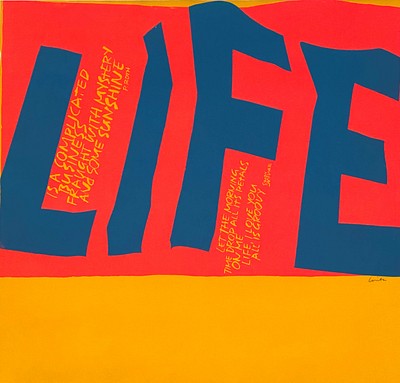

Oswaldo Guayasamin (Ecuadorian, 1919-1999) Painting Collage

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $10 |

| $100 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,500 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $15,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Apr 30, 2023

Fine Art Auction - 35th Anniversary Myers Antiques auctions@myersfineart.com

- Lot Description

Oswaldo Guayasamin (Ecuadorian - American, 1919-1999) Painting. Painted paper on paper collage painting. Signed lower right Guayasamin. Measures 8 inches high, 9.7 inches wide. Frame measures 9.5 inches high,11.5 inches wide. In good condition. From the estate of Academy Award winning film director Anthony Harvey.

From Askart.com: The following text was written and submitted by Jean Ershler Schatz, artist and researcher from Laguna Woods, California: Oswaldo Guayasamin (1919-1999) was born in Quito, Ecuador. He was the oldest of ten children in a poor family. He enrolled at Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes in Quito against his father's wishes and studied architecture and painting. Guayasamin is a passionate, plump and indefatigable Ecuadorian Indian (the name means white bird flying in Inca). He studied with Orozco and has a similar social consciousness, amounting to aching rage at Man's inhumanities, and a similar range of technique, from abstraction to hammer-blunt realism. But his subject matter, Ecuador, is all his own; he sees it as a tragic land. Following his first exhibition in Ecuador, he was invited by the US State Department to show in a traveling exhibit in the United States of America. He also traveled to Peru, Chile, Argentina and Bolivia and painted a series of 103 paintings focusing on life among the poor Indians and Blacks of Latin America. He exhibited in Quito, Caracas, Washington, DC and in Barcelona. He also painted murals, two of which are in Quito. He visited Cuba, China, Russia and painted many heads of state, including Salvador Allende. He dedicated a museum to the town of Quito. He died in 1999 in Quito. From Wikipedia: Guayasamín started painting from the time he was six years old. La Galería Caspicara, an art gallery opened by Eduardo Kingman in 1940, was one of the first places that Guayasamín was featured. His themes of oppression in the lower social classes allowed him to stand out and gain more recognition. El Silencio in particular, was a painting from this showcase that stood out. It marks a shift in Guayasamín's work from storytelling to focusing on his subjects symbolizing all human suffering. Guayasamín met José Clemente Orozco while traveling in the United States of America and Mexico from 1942 to 1943. They traveled together to many of the diverse countries in South America. They visited Peru, Brazil, Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, and other countries. Through these travels, he observed more of the indigenous lifestyle and poverty that appeared in his paintings. In 1988 the Congress of Ecuador asked Guayasamín to paint a mural depicting the history of Ecuador. Due to its controversial nature, the United States Government criticized him because one of the figures in the painting shows a man in a Nazi helmet with the lettering CIA on it. Oswaldo Guayasamín won first prize at the Ecuadorian Salón Nacional de Acuarelistas y Dibujantes in 1948. He also won the first prize at the Third Hispano-American Biennial of Art in Barcelona in 1955. In 1957, at the Fourth Biennial of São Paulo, he was named the best South American painter. The artist's last exhibits were inaugurated by him personally in the Luxembourg Palace in Paris, and in the Palais de Glace in Buenos Aires in 1995. In Quito, Guayasamín built a museum that features his work. His images capture the political oppression, racism, poverty, Latin American lifestyle, and class division found in much of South America.

Obituary from NY Times - Dec. 13, 2017: Anthony Harvey, Lion in Winter - Director and Kubrick Editor, Dies at 87.

It might have gone down as the most ridiculous scene in the most audacious film that Anthony Harvey ever worked on, but at least as Mr. Harvey told the story, a momentous event in the real world kept it from the moviegoing public. It was an epic two minutes worth of pie throwing, and it was originally to be the ending of - Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, - Stanley Kubrick's dark satire of the nuclear age. Mr. Harvey, the editor on that movie, was pretty pleased with the way the chaotic scene had come out. It was a brilliant piece of work, he once said. Who knows? I certainly thought it was. But the movie, which was scheduled for release in January 1964, was to receive its press premiere in late November 1963, right when all sorts of plans were thrown into turmoil by the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. That ending, how it started, the George Scott character threw a custard pie to the Russian ambassador, and it missed and hit the president, Mr. Harvey told the film journalist Glenn Kenny in 2009. Columbia Pictures, he said, was very nervous about anything to show the president, any president in that state. As a result, the pie-throwing scene was scrapped. Others involved with the movie have over the years given different explanations for the changed ending, but in any case the airborne pies were replaced with the now familiar montage of nuclear explosions - set to Vera Lynn's rendition of the song We'll Meet Again, an unsettling ending instead of a slapstick one. Mr. Harvey would go on to become a director himself, teaming with Katharine Hepburn on several films, most notably The Lion in Winter (1968), for which he was nominated for an Oscar. He died on Nov. 23 at his home in Water Mill, on Long Island, at age 87. The Brockett Funeral Home confirmed the death. Mr. Harvey was born on June 3, 1930, in London. His father, Geoffrey Harrison, died when he was young, and after his mother, the former Dorothy Leon, remarried, he took the surname of his stepfather, Morris Harvey, an actor. He got an early taste of the movie business when he was cast in a small part in the 1945 film "Caesar and Cleopatra," which starred Claude Rains and Vivien Leigh, but his real entree came when he landed a job as an editor for the British filmmakers John and Roy Boulting. He learned the art of editing as it was done in predigital days, pasting countless film clips together by hand. He received his first film-editor credits in 1956, on a short called - On Such a Night and the feature Private's Progress, a war comedy. He was the editor on Kubrick's - Lolita in 1962, which led to the - Dr. Strangelove assignment, a difficult one that involved cutting between three concurrent story lines, one set in the war room of the American government. We had a huge kind of war room of our own in the cutting room, Mr. Harvey told Mr. Kenny, and we put up pieces of paper representing every sequence in different order. It was Kubrick, he said in a 1994 interview with The New York Times, who told Mr. Harvey that he was ready to direct. It was Kubrick, too, who gave him an important piece of advice: If an actor is giving a dazzling performance, hold on to that shot and resist the temptation to cut away to, for instance, the reactions of other characters in the scene. In 1966, Mr. Harvey directed - Dutchman, a short film based on a play by LeRoi Jones, who would become better known as Amiri Baraka. Peter O'Toole was impressed enough by that film that he recruited Mr. Harvey for - The Lion in Winter, in which Mr. O'Toole starred as Henry II opposite Katharine Hepburn as Eleanor of Aquitaine. Working with her is like going to Paris at the age of 17 and finding everything is the way you thought it would be, Mr. Harvey said. Hepburn won an Oscar for her performance, splitting the award with Barbra Streisand, who won for Funny Girl. Mr. Harvey also directed Hepburn in a well-regarded television adaptation of Tennessee William's - The Glass Menagerie in 1973. John J. O'Connor, reviewing that film in The Times, called it a special TV event, demanding attention. It won four Emmy Awards. But Mr. Harvey's output as a director was limited. His handful of theatrical releases included the comedy - They Might Be Giants in 1971, the drama Richard's Things in 1981 and another Hepburn vehicle, Grace Quigley, in 1985. That movie was poorly received, and Mr. Harvey retreated from film directing, returning only in 1994 for This Can't Be Love, a television movie starring Hepburn and Anthony Quinn. He retired to his Long Island home, which he had acquired three years earlier. He leaves no immediate survivors. Mr. Harvey was comfortable working in Hollywood but preferred life on the East Coast, where the film business was not quite so all-consuming. He told of once having surgery in a Los Angeles hospital. As I was coming to, he recalled, the anesthesiologist said, - I'm very anxious to get into movies. - Shipping Info

-

All shipping arrangements and costs are the sole responsibility of the buyer. We are happy to assist in the transfer of merchandise to a shipper of your choice. Buyers should request a shipping quote prior to bidding. There are reliable shipping companies to use, and they include:

(1) The UPS Store:

Charlie Mosher

301 West Platt St

Tampa, FL 33606

(813) 251-9593

store3751@theupsstore.com

www.theupsstore.com/3751For a shipping quote, click the link below to get started on a quote OR to make payment for an existing quote: MyAuctionQuote.com/myers

(2) The UPS Store:

RayAnna Brodzinski

740 4th Street North

St. Petersburg, FL 33701

(727) 513-2400

shipping@store6886.com

www.theupsstore.com/6886(3) The UPS Store:

Rian Fehrman

5447 Haines Rd N,

St. Petersburg, FL 33714

(727) 528-7777

store6173@theuspsstore.com

www.theupsstorelocal.com/6173(4) Family Pak & Ship

Amel & Mohamed Hamda

2822 54th Avenue S.

St. Petersburg, FL 33712

727 865-2320

Raman@familypakandship.com

www.familypakandship.com(5) The UPS Store:

Gina Farnsworth

204 37th Ave N.

St Petersburg, FL 33704

(727) 822-5823

store3146@theupsstore.com

www.theupsstore.com/3146(6) The UPS Store:

200 2nd Ave South

St Petersburg, FL 33701

(727) 826-6075

store3248@theupsstore.com

www.theupsstore.com/3248(7) Craters & Freighters

(813) 889-9008

Fax (813) 884-8393

Tampa@cratersandfrighters.com

www.cratersandfreighterstampa.com (U.S. & International)(8) Orbit Professional Packing Crating

(888) 247-8540 or (727) 507-7447

lg@orbitppc.com

www.orbitppc.com (U.S. & International)LARGER ITEMS SHIPPING SUGGESTIONS

For items too large for standard shipping, such as furniture:

(1) Plycon - Furniture Transportation Specialists"

(954) 978-2000 (U.S. only)

lisa@plycongroup.com

www.plyconvanlines.com

You must submit a request on-line.(2) All Directions Moving

Specialist in moving furniture from FL to NY.

941-758-3800

alldirections@comcast.net

(3) Craters & Freighters

(813) 889-9008 or (877) 448-7447

Tampa@cratersandfreighters.com

(U.S. & International).(4) Westbrook Moving LLC

Makes regular trips up and down the east coast.

(404) 877-2870

westbrookdeliveries@gmail.com(5) Eastern Express

Owner Jeff Bills makes regular trips up and down the east coast.

(843) 557-6633

jb101263@yahoo.com(6) Can Ship US

Owner makes trips from Florida to Canada

Steve Fleury (905) 301-4866

canshipus@gmail.comThere are many other local and national shippers available in our area that we can refer you to. We are not responsible for any delays on the part of this third party shipper, should there be any. We recommend shipping all items insured. Should any damage occur to items transported by a third party, we are not held responsible. In the event that an item is approved for a return, shipping is not refundable.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB