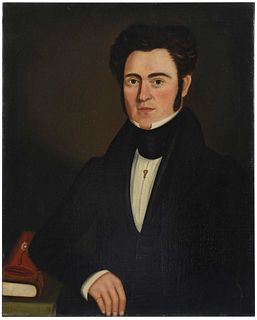

Elihu Root Jr. (American, 1881-1967) Oil Painting

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $10 |

| $100 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,500 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $15,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Apr 30, 2023

Fine Art Auction - 35th Anniversary Myers Antiques auctions@myersfineart.com

- Lot Description

Elihu Root Jr.(American, 1881-1967) Painting. Title - Sky. Oil on artist board painting. On the reverse titled Sky with the artist's name, Elihu Root Jr. c. 1958. Elihu Root was president of the Century Association from 1918-1927. The artist is the son of Elihu Root Senior, a 1912 Nobel Peace Prize recipient and United States Secretary of State between 1901 and 1909. Measures 24 inches high, 36 inches wide. Frame measures 27.5 inches high, 39.5 inches wide. In good condition.

From oneidadispatch.com: Elihu Root Jr., Hamilton College class of 1903 alumnus, was the son of esteemed administrator Elihu Root, 1912 Nobel Peace Prize recipient, Secretary of War and Secretary of State in the McKinley and Roosevelt Administrations, and founder of the U.S. Army War College in Carlisle, Pa. Elihu Root Jr.'s life was no less impressive. He was a distinguished lawyer and a founding partner of what would become the well-respected Dewey Ballantine law firm headquartered in New York City. He was one thing more. Root was also an amateur painter. Several of his works are now on display in a show of surprising power at Hamilton College's Emerson Gallery, Elihu Root Jr., Class of 1903: Lawyer-Painter. Over dinner in New York City in early summer 2003, John Root, Hamilton College wartime class of 1944 alumnus and Eliah Root Jr.'s nephew, told David Nathans, the Emerson Gallery's acting director, about a work of his uncle's that was hanging in the Main Gallery of the exclusive Century Association, also known as the Century Club, founded by 100 men of arts & letters in 1847. Intrigued, Nathans dropped by the club at 5th Avenue and 43rd Street. It has a fabulous collection of 19th and 20th century American art and some of the best Hudson River School paintings, Nathans said in a telephone interview from Princeton, N.J. There, within the walls of the classic McKim, Mead, and White building, he found Root's graceful 1956 oil on canvas female nude, Theodora. The subject matter and the way it was painted wasn't anything like what I was expecting from Elihu Root, said Nathans. It was well painted, a good crafted picture in tone and composition. The shadowing was great. The sense of depth.... There was a professionalism here, and I wanted to see more. Nathans left the Century Club convinced the work could not have been a one-shot. We had no idea when he began to paint, said Nathans, but Root, born in 1881, may have started as early as the 1920s. He only began to show his work at the Century Association's invitation from 1947 to 1966. He was 65 when he began showing his work, Nathans said. My sense is that before then he was just developing his skill and confidence. These exhibitions climaxed with the one-man show and retrospective Figures and Phantasies, which collected 43 of the artist's works, from Jan. 9 to Feb. 3, 1963 at the Century Club. Nathans and co-curators Deborah Pokinski, associate professor of art history, and three of her students, Hamilton 2004 graduates Talbot Gibson, Carolyn McLean and Laura Weatherly, might have recreated that show, which was the last time many of these works would be seen by the public for over 40 years. But as Root painted for pleasure and not his livelihood, many of the works were dispersed among family and friends as gifts. John Root had two in his New York City apartment, which, he admitted, weren't very good. I agreed with him, said Nathans. But the whereabouts of much of Root's best work, including several pieces from the Figures and Phantasies show, today is unknown. We found about half of the pieces from that 1963 show and were able to exhibit them, Nathans said. If we had a lot more time and the ability to track them down, we may have found more. Root, Nathans said, was truly an amateur in the sense that he didn't necessarily value the selling of these objects. He did them purely out of enjoyment. The quintet of Hamilton College curators amassed works largely from Root's family members in New York City, Clinton and its environs. The family has strong historical ties to Clinton and are Hamilton people. Roughly one-third to half of the works were retrieved from the attic of the College Hill home built by Elihu Root Sr., most recently owned by Molly Root, Elihu Root Jr.'s daughter-in-law, where they had languished since the early 1970s after Elihu's second cousin and second wife, Nancy died, Nathans said (a portrait of her is in the show). Molly herself died two days after Elihu Root Jr., Class of 1903: Lawyer-Painter opened on June 4. But not before she saw her father-in-law's works as an exhibition. Thirty-seven of the artist's creations, 18 of them once exhibited at the Century Club, compose the show. Included are landscapes and cloudscapes, but it is Root's female portraits and female nudes that reveal an extraordinary potency. According to the exhibition's catalogue, Harper's magazine wrote in 1967 that Root's nudes had gained considerable underground fame. The steel-grey toned Pat Carter is a totally beguiling portrait. Carter was a model and friend of Root's, but little else seems to be known about her, Nathans said. Other stand-out female portraits are the oil on board Lilith (1947) and Portrait Sketch of a Blond Woman oil on board (undated). Leda a la Mode (ca 1959), from the collection of Molly Root, is a heady oil on canvas that effectively stands apart from other works. But the beauty of Theodora, the exhibition's central work and perhaps Root's most stunning, is undercut by a curatorial flaw. This powerful work should have been given its own space, as Leda a la Mode had been given, to heighten its effect. The female nude, bequeathed by Root to the Century Club, was loaned to the club for nearly a decade before Root's death in 1967. The work was displayed during special banquets in the Main Dining Room and toasted by the club's male members. Fortunately it has not stirred controversy since the club was opened to women, who, according to Nathans, have accepted it in its proper artistic context. That wasn't the case at the National Press Club in Washington D.C., where in the 1997 an imbroglio erupted over a nude painting depicting the Greek courtesan Phryne. A small band of female members attached a meaning to the painting that was never intended. They saw it as a symbol of the time the Press Club was exclusively male and demanded the painting's removal. After a meticulous restoration to remove a film of smoke, Phryne was banished from the Press Club's walls. Root's nude oil Bottoms Up (1963) is a playful work. It's the most kitschy in the group, Nathans opined, reflective of a Playboy magazine type of art of the period. Another nude, the mythology-based Persephone, follows Rene Magritte. That wouldn't have been unusual since Root traveled in circles of arts & letters, said Nathans. His brother was an avid art collector and knew many artists in New York City. Also, Hamilton students of Root's day would have been well-steeped in classical stories. Here Persephone, queen of the underworld, is contemporized with a pageboy haircut. She's depicted holding an empty chalice as the River Lethe snakes in the background. Among the more atypical among Root's works are Shriek and Shriek II. Both evoke a nightmarish Mardi Gras. Root's landscapes are among the less-satisfying works in the exhibition, but Plum Point, with its moon drenched shore, is especially noteworthy. The Emerson Gallery has brought Root's work out of obscurity and into the public eye. It seems entirely appropriate then to give him, even after a 37-year lapse, his proper due as an artist just as the Century Club had done while he lived. - Shipping Info

-

All shipping arrangements and costs are the sole responsibility of the buyer. We are happy to assist in the transfer of merchandise to a shipper of your choice. Buyers should request a shipping quote prior to bidding. There are reliable shipping companies to use, and they include:

(1) The UPS Store:

Charlie Mosher

301 West Platt St

Tampa, FL 33606

(813) 251-9593

store3751@theupsstore.com

www.theupsstore.com/3751For a shipping quote, click the link below to get started on a quote OR to make payment for an existing quote: MyAuctionQuote.com/myers

(2) The UPS Store:

RayAnna Brodzinski

740 4th Street North

St. Petersburg, FL 33701

(727) 513-2400

shipping@store6886.com

www.theupsstore.com/6886(3) The UPS Store:

Rian Fehrman

5447 Haines Rd N,

St. Petersburg, FL 33714

(727) 528-7777

store6173@theuspsstore.com

www.theupsstorelocal.com/6173(4) Family Pak & Ship

Amel & Mohamed Hamda

2822 54th Avenue S.

St. Petersburg, FL 33712

727 865-2320

Raman@familypakandship.com

www.familypakandship.com(5) The UPS Store:

Gina Farnsworth

204 37th Ave N.

St Petersburg, FL 33704

(727) 822-5823

store3146@theupsstore.com

www.theupsstore.com/3146(6) The UPS Store:

200 2nd Ave South

St Petersburg, FL 33701

(727) 826-6075

store3248@theupsstore.com

www.theupsstore.com/3248(7) Craters & Freighters

(813) 889-9008

Fax (813) 884-8393

Tampa@cratersandfrighters.com

www.cratersandfreighterstampa.com (U.S. & International)(8) Orbit Professional Packing Crating

(888) 247-8540 or (727) 507-7447

lg@orbitppc.com

www.orbitppc.com (U.S. & International)LARGER ITEMS SHIPPING SUGGESTIONS

For items too large for standard shipping, such as furniture:

(1) Plycon - Furniture Transportation Specialists"

(954) 978-2000 (U.S. only)

lisa@plycongroup.com

www.plyconvanlines.com

You must submit a request on-line.(2) All Directions Moving

Specialist in moving furniture from FL to NY.

941-758-3800

alldirections@comcast.net

(3) Craters & Freighters

(813) 889-9008 or (877) 448-7447

Tampa@cratersandfreighters.com

(U.S. & International).(4) Westbrook Moving LLC

Makes regular trips up and down the east coast.

(404) 877-2870

westbrookdeliveries@gmail.com(5) Eastern Express

Owner Jeff Bills makes regular trips up and down the east coast.

(843) 557-6633

jb101263@yahoo.com(6) Can Ship US

Owner makes trips from Florida to Canada

Steve Fleury (905) 301-4866

canshipus@gmail.comThere are many other local and national shippers available in our area that we can refer you to. We are not responsible for any delays on the part of this third party shipper, should there be any. We recommend shipping all items insured. Should any damage occur to items transported by a third party, we are not held responsible. In the event that an item is approved for a return, shipping is not refundable.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB