EXTREMELY IMPORTANT SHENANDOAH (NOW PAGE) CO., SHENANDOAH VALLEY OF VIRGINIA, JOHANNES SPITLER PAINT-DECORATED YELLOW PINE BLANKET CHEST

Lot 492

Categories

Estimate:

$250,000 - $300,000

Absentee vs Live bid

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $10 |

| $200 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $3,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $30,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

By Jeffrey S. Evans & Assoc., Inc.

Jun 20, 2015 - Jun 21, 2015

Set Reminder

2015-06-20 09:30:00

2015-06-21 09:30:00

America/New_York

Bidsquare

Bidsquare : Important Catalogued Auction of Americana & Fine Antiques

https://www.bidsquare.com/auctions/jeffrey-evans/important-catalogued-auction-of-americana-fine-antiques-706

Jeffrey S. Evans & Assoc., Inc. info@jeffreysevans.com

Jeffrey S. Evans & Assoc., Inc. info@jeffreysevans.com

- Lot Description

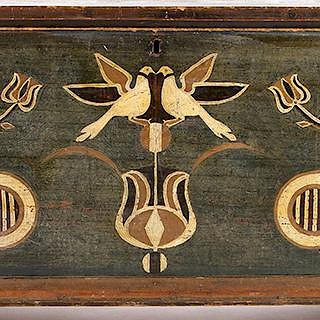

EXTREMELY IMPORTANT SHENANDOAH (NOW PAGE) CO., SHENANDOAH VALLEY OF VIRGINIA, JOHANNES SPITLER PAINT-DECORATED YELLOW PINE BLANKET CHEST, the hinged rectangular lid with applied edge molding of square profile with angled lower edge over a dovetailed case with applied ogee base molding and cut-out bracket feet. Interior with lidded till. Original wrought-iron strap hinges with triangular terminals. The moldings, feet, and bottom board are all attached with wooden pins, and the top corners of the dovetailed case are secured with wooden pins as well. Two wrought-iron nails are used to attach the rear foot supports. Painted-decoration to the lid incorporates inverted hearts balancing inverted crescents suspended on thin, prominently knopped, stems, and the front panel design features a central zone with lovebirds perched atop an abstract tulip form flanked by parallel outer zones, each with a triple-bloom tulip-like form issuing from the tip of an inverted heart containing dual barred orbs. Reserve. Circa 1800. 23" H, 47 1/2" W, 21 1/4" D.

Published: Donald Walters - "Johannes Spitler: Shenandoah County, Virginia, Furniture Decorator", The Magazine Antiques, Vol. 108, No. 4 (October 1975), p. 734, fig. 6.

Provenance: Property of a descendent of the original owner. See catalogue note for details.

Catalogue Note: In the field of American Decorative Arts, the paint-decorated furniture of Johannes Spitler (Virginia/Ohio, 1774-1837) of the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia holds a special place. Working during the nascent years of the Republic in an isolated region of the country, Spitler developed an iconic style by blending Old World traditions with New World techniques. His paint-decorated case pieces now reside in numerous institutions throughout the country, and the landmark 2004 sale by auctioneer Jeffrey S. Evans of the Modisett family hanging cupboard, a masterpiece decorated by Spitler, still holds the record auction price for American folk art paint-decorated furniture at $962,500. Since the artist was first identified by Don Walters in his 1975 article for The Magazine Antiques, the body of Spitler’s work, and our understanding of it, has continued to grow as unrecorded pieces come to light and new information is discovered. The present example, descended directly in the Long family of Shenandoah (now Page) County, Virginia, adds a new chapter to the story and stands out amidst the total group for its quality of design, outstanding condition, and fresh-to-the-market provenance. The first of eight children, Johannes Spitler was born in October of 1774 at Mill Creek in what was then Shenandoah County, Virginia and died in 1837 in Fairfield County, Ohio. His grandfather, John Spitler (1720-1752), was a Swiss immigrant and one of the early settlers of the Massanutten region, as it was known at the time. This area of the northern Shenandoah Valley, situated along the South Fork of the Shenandoah River between Massanutten Mountain (then called Buffalo Mountain) to the west and the Blue Ridge Mountains to the east, was settled in 1733 by a group of fifty-one Swiss and German settlers, who, fleeing religious persecution in Europe, had secured land in the New World in order to establish a new life. These people are generally referred to as "Swiss Mennonites", a broad term that encompassed an evolving religious movement in Switzerland and Germany during the Reformation. Though John Spitler arrived shortly after the initial wave of Swiss settlers, he undoubtedly shared common religious, cultural, and social bonds with this first group. He died young, however, at age 32, leaving behind a wife and two young children. The youngest of these two children, Jacob Spitler (1749-1829), would go on to lead a long and productive life, serving in the Revolutionary War and later participating in one of the earliest westward migrations in the nation’s history. He married Nancy Henry (1752-1826) in Shenandoah County in 1773, and a year later she gave birth to a son, Johannes. Whether Johannes Spitler ever received any sort of training or apprenticeship in a trade or profession is unclear at this point, but it is clear that, by the final years of the 18th century, he was already, in his early 20s or perhaps even earlier, creating paint-decorated furniture for clients in the area. For just over a decade, it appears that Spitler produced a relatively high number of these pieces, as much as twenty-five per year by some estimates. Thirty-one pieces with painted decoration attributed to Johannes Spitler have been documented at this point, and such a significant survival rate indicates that the decorator was fully engaged in a successful enterprise, one that likely provided an important source of supplemental income for a full-time farmer such as he was. Nonetheless, despite this success in Virginia, Johannes and his family moved west to Ohio in 1809, where they joined his father, Jacob, and mother, Nancy Ann, and settled in what would become Fairfield County. Jacob Spitler and his wife soon became members of the newly formed Pleasant Run Baptist Church there, which had been founded in 1806 by Lewis Sites/Seitz from Rockingham County, Virginia, an area just west of the Spitler home in the Shenandoah Valley. Johannes Spitler (his name now anglicized to "John") was most likely a member of the Pleasant Run congregation as well, though no definitive record of his membership exists. Living in close proximity to his parents and many other Massanutten natives in this new western land, Johannes must have sensed at some point after his arrival that he was marking the beginning of a new period, one filled with opportunity. It appears, however, that the second phase of Spitler’s life was marked with much less success than the first. In fact, according to new research by independent scholar and author, Elizabeth "Betsy" Davison, Johannes Spitler died impoverished, his will bearing witness to the significant amount of debt he had accumulated. The stark reality reflected in his final will, combined with his artistic silence while in Ohio, indicate that Johannes Spitler’s life in the west must have been very different from his life in Virginia. His beautifully designed gravestone, probably paid for out of pity by the church congregation and which still stands in the Pleasant Run cemetery, features a willow tree and a short verse in the lower inscription: "Stop my friends and take a view / Of the cold grave allotted you / Remember well that you must die / And turn to dust as well as I". In a final connection with the Shenandoah Valley, the stone, signed "John Strickler / Stone cutter", was worked by a member of the Strickler family, which had set up an enterprise in the same area and also migrated from Shenandoah County in the first years of the 19th century. It is not entirely clear why the Spitlers and several other families left the Shenandoah Valley for the newly formed state of Ohio. Were they simply in search of greater opportunity, or were they prompted to leave their home in Massanutten by something specific? Divisions within religious denominations and even individual churches were common in this period, so it is possible that some sort of schism within the Mennonites of Massanutten may have contributed to the departure of a number of area families, including the Spitlers. In this light, perhaps it is more than mere coincidence that Martin Kauffman, a pastor at Mill Creek Baptist Church where the Spitlers were members, died in 1806, a year before the extended Spitler family journey west begins. Whatever the case may be, Johannes Spitler left the Valley in 1809, and his decade-long career as a folk artist, one of the most important in early America, came to a close, for it appears that Johannes Spitler stopped producing paint-decorated furniture when he moved to Ohio. Only two examples of his work have surfaced with Ohio histories, and it is quite possible that these chests were brought from Virginia during the migration. How could such a prolific and successful craftsman in the prime of his working life suddenly cease output? Did something happen on the journey west? Was he injured in some way that would prohibit him from continuing in this type of work? Did the social and cultural appetite for his brightly painted and highly stylized pieces not exist in Ohio as it had in Virginia? In the absence of direct evidence, we can only speculate. To date, twenty-eight chests, two clocks, and one hanging cupboard with painted decoration attributed to Johannes Spitler have been documented. All of these pieces are constructed of yellow pine and, with the one exception of the Jacob Strickler tall case clock now at the Museum of American Folk Art and the hanging cupboard now in the Jane Katcher Collection, share common construction characteristics. For the chests in particular, these features include exposed and wedged dovetailing to the case and feet; generous use of wooden pegs to secure lid moldings, base moldings, feet, and the upper joint at each top corner of the case; lids attached with iron strap hinges; and feet of a consistent ogival profile. It is not known for sure at this point who the cabinetmaker was for these pieces, whether it be Spitler himself or someone else, but it does appear that a single hand was primarily responsible for the construction of the forms that are decorated by the artist’s hand. More research on this area of Spitler study is undoubtedly forthcoming. Within the whole group of case pieces with painted decoration attributed to Johannes Spitler, there are clearly two styles or modes of production during the artist’s career. The first, referred to as the Geometric Group, incorporates, as the name suggests, primarily straight-edge-and compass-drawn geometric forms, and at least nine examples from this group include inscriptions with dates and what appears to be a numbering system. The second, referred to as the Figural Group, incorporates primarily straight-edge, compass, and template-executed elements of a more representational nature, including birds, hearts, tulips, and crescents. These examples from the second group, in which the Long family chest is included, are typically not inscribed, but continue to exhibit the same tendency towards attaining balance in design through a pattern of segmentation and alteration. It is not clear whether Spitler’s work evolved chronologically or whether the existence of the dual groups represents two distinct stylistic approaches the artist employed throughout his career, but the differences do exist. Was Spitler offering his clients a choice between the two styles throughout his working period, or did the style simply change? Betsy Davison has speculated that Spitler employed different modes of decoration based on the specific religious affiliation of the customer. In this case, decorative schemes associated with the Geometric Group were adopted for the more conservative Mennonite clients in the area, and patterns and forms typical of the Figural Group were utilized for other, more worldly, customers of differing religious affiliations. In this light, it appears that the demand for Spitler’s unique paint-decorated creations extended across a broad swath of Massanutten society, and that the decorator, much like a popular artist receiving multiple commissions, was quite busy during this period of production. Whatever the impetus for the differentiation of style may be, the artist was able to continue in the Old World tradition of decorating case pieces, particularly chests, with painted designs drawn from a shared visual vocabulary. This tradition remained strong in Pennsylvania through the end of the 18th century and into the early years of the 19th century, and, not surprisingly, surviving examples of the form with Pennsylvania histories far outnumber surviving examples from Virginia. In this respect, the volume of Spitler’s documented work seems all the more remarkable. It is rare to identify an early American folk artist, even more so to locate such an extensive body of this artist’s work. Working within a general tradition, Spitler developed a unique style in a unique region of the country, and, in doing so, was able to satisfy what must have been a strong demand for brightly painted and elaborately decorated furniture forms. And brightly painted these forms were. Composed in colors of what conservator Chris Shelton has called "vivid intensity", Spitler pieces originally would have appeared much brighter in hue than their currently oxidized states indicate, contradicting preconceived notions about the supposedly hyper-conservative nature of early Mennonite culture. In fact, it is Spitler himself who most clearly defies our romanticized understanding of the backcountry craftsman. A master of paint and design, he used the most modern of materials and techniques for his work despite his relatively isolated location and probable lack of formal training. The Prussian blue, lead white, red lead, lampblack, and red ochre that the artist employed were all "commercially available pigments" and likely came by way of Philadelphia down the Great Wagon Road to the growing crossroads town of New Market on the western side of the Massanutten Range or the nascent village of Luray just north of the Massanutten community. Additionally, Spitler appears to have incorporated these modern elements, including the use of stencils or templates, as an integral part of a "streamlined methodology" employed for the systematic production of paint-decorated case pieces. We do not typically associate backcountry decorative artisans with methodologies, but with Spitler such is the case. Working in zones and using compass, straight edge, and template, the artist scribed out his designs and then applied the painted decoration, beginning with the red, white, and black used in the imagery, followed by the blue background. As is the case with the Long family chest, several examples were first painted all over with red ochre primer or undercoat and then treated in the manner described above. With both techniques, Spitler achieved a degree of precision in his painted ornamentation that creates a bold effect pleasing to the eye. As with all great folk art, Spitler’s work rides the ineffable line between sophistication and naivete, and his highly individual designs continue to startle us with their beauty. The current example from the Long family, nearly untouched for over two hundred years, is just such a revelation, and its appearance on the market represents an exceedingly rare opportunity to acquire an outstanding work by one of early America’s premier folk artists. The Long family chest exhibits the standard tripartite divisional arrangement and naturalistic imagery that is associated with the second group of Spitler chests. Here the decorator employs a design featuring a central zone with lovebirds perched atop an abstract tulip form flanked by parallel outer zones, each with a triple-bloom tulip-like form issuing from the tip of an inverted heart containing dual barred orbs. In this case, Spitler’s meticulous preparation in decoration is most evident (see catalogue photos), and the artist’s orderly use of measured scribe lines to establish a grid within which to work allows for a caliber of precision not typically encountered in folk art. Additionally, the Long chest retains a remarkably well preserved paint-decorated design to the lid that is unlike any heretofore documented (see catalogue photos). The pattern in this instance is laid out in three panels or zones, as in the front panel, and incorporates inverted hearts balancing inverted crescents suspended on thin, prominently knopped stems. Considering that most chests were likely used for both storage and seating, painted decoration to the lid on Spitler chests rarely survives intact. This unusual aspect of the Long chest affords us the uncommon opportunity to observe the ways in which the artist was able to use the lid as a decorative extension of the front panel by echoing many of the same motifs employed in the principal design. The overall effect is dramatic. Indeed, the Long family chest exemplifies those qualities of precision and balance for which Spitler is celebrated and clearly stands out as the product of a master craftsman working at the peak of his creative powers. The present chest with painted decoration by Johannes Spitler descended directly in the family of pioneer Shenandoah Valley settler, Philip Long (Germany/Virginia, 1678-1755). Remarkably, it has remained in the immediate region of Massanutten and in the same family for its entire 215-year existence. Rarely do objects of this significance remain in the families for which they were created for such an extensive period, and this additional quality of the Long chest only adds to its importance. This chest was likely made in the years following the 1795 marriage of Reuben Long (1773-1830) and Mary Ann Shank Long (1773-1831), possibly in conjunction with the birth of their first child, Elizabeth, and has descended through six generations of the Long family to the present owner. Reuben Long was the great-grandson of pioneer Philip Long (Lung), who, along with a group of other men and their families, established in 1729 a settlement in what was then referred to as Massanutten. Long had purchased his property from business associates of Jacob Stover, a land speculator who had applied in 1728 to the council in Williamsburg for a 10,000 acre land grant on the South Fork of the Shenandoah River. William Beverley initiated a suit against the settlers shortly after their arrival, claiming that they had no title to the land, but the suit was dismissed in 1733 by Governor Gooch, and the property was officially deeded to Stover and another speculator, Ludwick Stone. Philip Long and his son Paul purchased their properties from Stone in 1737 and began to establish homesteads and farms. Philip Long acquired 800 acres on the eastern side of the South Fork, upon which he built what is known as Fort Long, a stone dwelling with defensive features used for protection against attacks from Native Americans. In 1740, Philip Long and Abraham Strickler, another pioneer Massanutten settler and great-grandfather of fraktur artist Jacob Strickler, traveled to record their deeds in newly formed Orange County. While there, probably prompted by the difficult journey over the Blue Ridge Mountains, Long and Strickler petitioned the court for assistance in building a road from Thornton’s Mill on the eastern side of the Blue Ridge all the way across the Massanutten Valley and over what was then called Buffalo Mountain to the town of New Market where it could connect with the Great Wagon Road. The court appointed Long and Strickler to oversee the project, and the thoroughfare they laid out, which became the basic path for today’s Route 211, is one of the oldest roads in the Shenandoah Valley. Philip’s son, Paul, also played an important role in the early settlement of Massanutten, establishing a fort on his property as well. Paul Long probably served with the Augusta County militia and may well have seen action in the French and Indian War during Braddock’s defeat at the Battle of Monongahela in 1755. Long died only a few years later in 1759, leaving behind three children. One of those children was eighteen-year-old Philip Long (1742-1826), sometimes referred to as Philip Long, Sr., another important member of the family who would go on to serve in the Revolutionary War. Long was at the Battle of Point Pleasant in 1774, which included fierce fighting against a combined Indian force, and later in 1778 and 1779 participated in the important expeditions of Colonel George Rogers Clark, whose actions in what was then called the Northwest Territory helped to secure vast swaths of land for the new nation upon gaining independence. Following his discharge from the Army in present-day Indiana, Philip Long then walked nearly 1,100 miles back to his home in Shenandoah County. In another interesting twist to the story, Philip Long may have served in the same militia as Jacob Spitler (the father of Johannes Spitler) during the war for American independence, and the two must have known each other as a result of their shared experiences. Additionally, Philip’s son, Reuben, was roughly the same age as Johannes, and, as both were first-born sons of Revolutionary veterans as well, it is possible that Reuben Long and Johannes Spitler had been acquainted long before the present chest was commissioned. Philip Long’s son, Reuben, was five years old when his father left home in 1778 with Captain Michael Reader’s Militia Company on their way to join Colonel Clark’s force. Reuben Long, the first-born son, received a healthy inheritance from his father, including "seven hundred acres of land lying in said county on the west side of the South River of Shenandoah". Not surprisingly, Reuben remained in the area, married, and raised four children with his wife, Mary Ann Shank. According to family history, the present chest with painted decoration by Johannes Spitler was probably made for Reuben and Mary Ann in the years after their marriage in 1795. Reuben Long died in 1830 without a will, and an extensive inventory of his estate was tabulated in preparation for a sale. His widow, Mary Ann, purchased almost all of the furniture at the sale, including a "clock and case", a "case of drawers", and "two chests". It is quite possible that the present example with decoration by Spitler is one of the "two chests" mentioned in the sale record of Reuben Long’s estate, but, unfortunately, no such direct evidence has been discovered at present. Upon the death of Mary Ann Shank Long in 1831, family tradition states that the chest then passed to her son, Philip Shank Long (1813-1897), who became one of the wealthiest and largest landowners in what was now called Page County. In 1872, Long acquired title to the farm and home, called "Wallbrook", of Peter Brubaker as part of a complicated and lengthy legal procedure to resolve a delinquent debt. Philip Shank Long’s extensive will from 1897 includes an elaborate distribution of properties amongst his children, including "Lot No. 1 of the Peter Brubaker land" as well as "such personal property as I may have, or hereafter set aside" to his youngest son, John William Long (1853-1930). The Long family Spitler chest was probably moved to the Brubaker home at "Wallbrook" (built c. 1820) when John William Long took possession of the property upon his father’s death. J. W. Long is the great-grandfather of the present owner, the chest having remained at Wallbrook Farm since it had been moved there over one hundred years earlier. To our knowledge this chest represents the last Spitler-decorated piece remaining in the family of the original owner and had never left the community where it was made until transported to our gallery earlier this year.The Long family chest survives in remarkable original condition with expected wear to the decoration on the lid and minor areas of the feet and base molding. The lid is slightly ill-fitting due to shrinkage, and several of the screws in the original wrought-iron strap hinges appear to have been replaced. An old (probably 19th century) layer of thin varnish covers the painted decoration and has served as a protective layer against the elements and standard usage wear. Blocking was added to the original feet in the 19th century to hold casters, and screws, which travel through the facings and attach to the blocking behind, were added at that time as well. There are early repairs to the proper left front foot dating from the first quarter of the 19th century which consist of two wooden pins inserted through the bottom of the original foot facings to stabilize two horizontal cracks. All elements of the foot are original, and this early repair is only evident on the underside.Condition

- Shipping Info

-

The buyer is responsible for all associated shipping costs.

To expedite shipping, we recommend payment by Visa® or MasterCard®, cashier's/certified check or money order.

Standard shipping charges include our packing fee and the cost of shipping with insurance (based on current UPS or USPS fees). A handling fee may be charged for packages that must be taken to the Post Office. Alternate shipping options

Our account with UPS provides for a daily pick up, therefore no handling fee applies to packages shipped via UPS.

Special requests for alternate methods of shipping are acceptable, but may result in an additional cost to you.

We pack for shipping only upon request and we work in order of request.Once a package is ready to ship it is weighed, measured and processed through the USPS and/or UPS system in order to determine cost of shipping including insurance and additional services (e.g. delivery confirmation) as applicable.Shipping charges include a fee for packing time and materials. Our time is billed at $15.00 per hour and we use recycled materials whenever possible at no cost to the buyer. If purchased supplies (e.g. boxes) are used, that cost is passed on to the buyer as part of the packing fee.(Our $15.00/hour fee is prorated, therefore if a packing job requires 30 minutes and no purchased supplies, the total packing fee would be $7.50.)The actual cost of shipping/insurance and packing/materials cannot be determined until packing is completed. Once known, the shipping charges are applied to the buyer’s invoice and he/she is notified of the cost by email (or by phone if we have no email).We may pack/ship for 150-250 people after each auction. The entire post-auction process generally takes 2-3 weeks to complete.We work as quickly as possible, however, not everyone can be first in line. If you are are in the second half of our packing order, it may be 2-3 weeks before your package ships. We appreciate your patience and assure you that we will take excellent care of your items.

Buyers are not obligated to accept our packing/shipping service and are welcome to make other arrangements if desired.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB