[Hamilton, Alexander] [First Bank of the United States] Autograph Letter, signed

About Seller

2400 Market St

Philadelphia, PA 19147

United States

Established in 1805, Freeman’s Auction House holds tradition close, with a progressive mind-set towards marketing and promotion, along with access to a team of top experts in the auction business. And now with offices in New England, the Southeast, and on the West Coast, it has never been easier to ...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $200 |

| $3,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,000 |

| $30,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Oct 25, 2021

Freeman's is honored to present The Alexander Hamilton Collection of John E. Herzog, a single-owner sale of Alexander Hamilton material, on October 25. Curated by Darren Winston, Head of the Books and Manuscripts Department. Freeman's info@freemansauction.com

- Lot Description

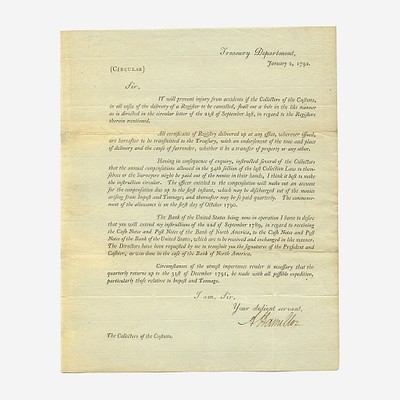

[Hamilton, Alexander] [First Bank of the United States] Autograph Letter, signed

Partisan fighting leads Alexander Hamilton to refute claims of impropriety regarding the operations of the Bank of the United States

"I rather avoid interference in the affairs of the Bank and am seldom consulted except as to general principles and as to those not always"

Philadelphia, Aug(ust) 27, 1792. One sheet folded to make four pages, 9 15/16 x 7 7/8 in. (252 x 200mm). Autograph Letter, signed and executed entirely in the hand of Alexander Hamilton as the first United States Secretary of the Treasury, to John Hopkins, Loan Officer for the State of Virginia, refuting any direct influence over the First Bank of the United States: "I have received your private letter/of the 16th; and am obliged by the information it/contains, which I need not assure you will have/its due weight in a final comparison of the pretension,/of the different candidates, as far as I may have/any agency in the matter. This however is truly very/problematical; as I rather avoid interference in the/affairs of the Bank and am seldom consulted except as to/general principles and as to those not always..." Addressed and free franked by Hamilton on verso, docketed to same in a different hand. Creasing from original folds; scattered minor tears along edges and folds; remnants of wax seal, with small loss to edge, on verso.

This rare letter reflects the incessant attacks leveled against Hamilton and his seemingly continuous need to defend his name. The very existence of the Bank was a constant source of partisan discord and would lead to numerous Congressional investigations against him in the years to come (see lots 28, 29, 30, 35).

Ever since Alexander Hamilton submitted his report to Congress on a national bank, in December 1790, partisan tensions flared between those who supported it and those who were against it. The divide was roughly split along sectional lines of North and South, with the northern congressional majority firmly supporting the Bank, while the southern minority, led by Virginia Congressman James Madison, was vehemently against it. Madison and his southern delegates, who were rich in land and enslaved people, and often debtors to Northern merchants, viewed the Bank as a threat to their agrarian livelihood, believing that it would lead to their exploitation at the hands of a powerful northern aristocracy. Madison would go on to argue against the Bank's constitutionality in violating the necessary-and-proper clause in Article I, Section 8. The bitter partisan feud almost led to Washington's vetoing the bill, but he instead sought out the opinions of his cabinet�Attorney General Edmund Randolph, Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, and Secretary of the Treasury Hamilton. Washington would go on to support Hamilton's more flexible interpretation of the Constitution, and sign the bill into law. The bill's passage only enflamed partisan tensions and, coupled with other aspects of Hamilton's ambitious agenda, helped form the country's first two political parties: the Federalists�those aligned with Hamilton, Washington's administration, and a strong central government�and the Democratic-Republicans�those aligned with Madison and Jefferson, who favored an agrarian-based economy and a decentralized government.

By August 1792 the nation had just recovered from its first financial crisis, the Panic of 1792. The Panic was due in part to a speculative frenzy created by the newly opened Bank and the expansion and contraction of credit that followed. Due to Hamilton's many legislative victories, and the ensuing Panic, Jefferson and Madison had come to view Hamilton as nothing short of a threat to the Republic. The political divide was firmly drawn in Congress, and felt even more strongly in Washington's cabinet as Hamilton and Jefferson engaged in a campaign to undermine each other. As Ron Chernow observes about the nature of this political divide, "By 1792, both political parties saw their opponents as mortal threats to the heritage of the Revolution. But the special mixture of idealism and vituperation also stemmed from the experiences of the founders themselves. These selfless warriors of the Revolution and sages of the Constitutional Convention had been forced to descend from their Olympian heights and adjust to a rougher world of everyday politics, where they cultivated their own interests and tried to capitalize on their former glory. In consequence, the founding fathers all appear to us in two guises: as both sublime and ordinary, selfless and selfish, heroic and humdrum. After the tenuous unity of 1776 and 1787, they had become wildly competitive and sometimes jealous of one another. It is no accident that our most scathing portraits of them come from their own pens." Hamilton and Jefferson's own pens found expression in some of the most vitriolic newspaper articles written by them during the newspaper wars that escalated during the time this letter was written. The Democratic-Republic paper, Philip Freneau's, National Gazette, often published articles by Jefferson, while the Federalist-aligned Gazette of the United States, published by John Fenno (see lot 6), often saw Hamilton ghostwriting articles to counter various charges of corruption and crypto-monarchism. In early August 1792, Hamilton crossed the partisan newspaper line and took to the pages of Freneau's Gazette then began publishing a series of articles written under the guise of "An American" and "Civis." In them he wrote disparagingly of Jefferson by name, and attacked him on a number of fronts. This bitter war engulfed much of the summer and fall of 1792, and further divided Washington's cabinet, often involving Washington in a futile attempt to quell the discord, and would go on to see Jefferson's resignation as Secretary of State at the end of 1793.

Profiles in History, 2016, Sale 84, Lot 73

- Shipping Info

-

No lot may be removed from Freeman’s premises until the buyer has paid in full the purchase price therefor including Buyer’s Premium or has satisfied such terms that Freeman’s, in its sole discretion, shall require. Subject to the foregoing, all Property shall be paid for and removed by the buyer at his/ her expense within ten (10) days of sale and, if not so removed, may be sold by Freeman’s, or sent by Freeman’s to a third-party storage facility, at the sole risk and charge of the buyer(s), and Freeman’s may prohibit the buyer from participating, directly or indirectly, as a bidder or buyer in any future sale or sales. In addition to other remedies available to Freeman’s by law, Freeman’s reserves the right to impose a late charge of 1.5% per month of the total purchase price on any balance remaining ten (10) days after the day of sale. If Property is not removed by the buyer within ten (10) days, a handling charge of 2% of the total purchase price per month from the tenth day after the sale until removal by the buyer shall be payable to Freeman’s by the buyer. Freeman’s will not be responsible for any loss, damage, theft, or otherwise responsible for any goods left in Freeman’s possession after ten (10) days. If the foregoing conditions or any applicable provisions of law are not complied with, in addition to other remedies available to Freeman’s and the Consignor (including without limitation the right to hold the buyer(s) liable for the bid price) Freeman’s, at its option, may either cancel the sale, retaining as liquidated damages all payments made by the buyer(s), or resell the property. In such event, the buyer(s) shall remain liable for any deficiency in the original purchase price and will also be responsible for all costs, including warehousing, the expense of the ultimate sale, and Freeman’s commission at its regular rates together with all related and incidental charges, including legal fees. Payment is a precondition to removal. Payment shall be by cash, certified check or similar bank draft, or any other method approved by Freeman’s. Checks will not be deemed to constitute payment until cleared. Any exceptions must be made upon Freeman’s written approval of credit prior to sale. In addition, a defaulting buyer will be deemed to have granted and assigned to Freeman’s, a continuing security interest of first priority in any property or money of, or owing to such buyer in Freeman’ possession, and Freeman’s may retain and apply such property or money as collateral security for the obligations due to Freeman’s. Freeman’s shall have all of the rights accorded a secured party under the Pennsylvania Uniform Commercial Code.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB![[Hamilton, Alexander] [First Bank of the United States] Autograph Letter, signed](https://s1.img.bidsquare.com/item/l/9470/9470960.jpeg?t=1MwoES)

![[Hamilton, Alexander] [First Bank of the United States] Autograph Letter, signed](https://s1.img.bidsquare.com/item/s/9470/9470960.jpeg?t=1MwoES)