Rare 1864 Civil War Navy Substitute Form, By Future Mayor of Saco, Maine

Lot 226

Estimate:

$800 - $1,000

Absentee vs Live bid

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $10 |

| $200 | $20 |

| $300 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $200 |

| $3,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,000 |

| $30,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

| $200,000 | $20,000 |

| $300,000 | $25,000 |

| $500,000 | $50,000 |

About Auction

By Early American History Auctions

Jun 1, 2019

Set Reminder

2019-06-01 12:00:00

2019-06-01 12:00:00

America/New_York

Bidsquare

Bidsquare : Historic Autographs, Colonial Currency, Political Americana & Revolutionary War Era

https://www.bidsquare.com/auctions/early-american-history-auctions/historic-autographs-colonial-currency-political-americana-revolutionary-war-era-4152

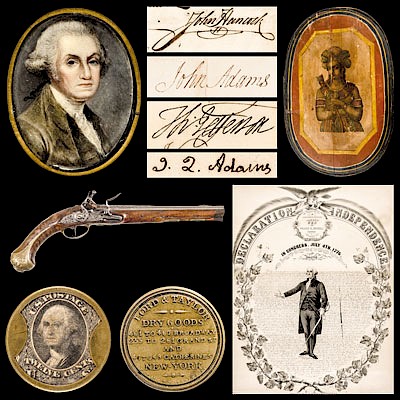

Historic Autographs, Coins, Currency, Political, Americana, Historic Weaponry and Guns, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, Early American History Auctions auctions@earlyamerican.com

Historic Autographs, Coins, Currency, Political, Americana, Historic Weaponry and Guns, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, Early American History Auctions auctions@earlyamerican.com

- Lot Description

Civil War Union Documents

Rare 1864 Civil War "Substitute for the Navy" Form By the Future Mayor of Saco, York County, Maine

September 2, 1864-Dated Civil War Period, Partially-Printed Document, Portland Maine Citizen Officially Enlists as a "Substitute" for the Navy, Choice Very Fine.

Civil War, Maine Substitute for Navy Form, 1864. This 5 x 7.5" form on official 'Provost Marshal's Office' of the 1st Congressional District of Maine with embossed seal at top, confirms a William O. Freeman of Saco, Maine to be duly enlisted and mustered into the U.S. Service, 51 Sub-District. Form language is stating as a 'recruit', crossed out, he is written in as a 'Substitute' for the Navy (with "Regiment, Maine Volunteers" also crossed out. Signed by Captain & Prov. Marshal Chas H. Doughty, 1st Dist. Mustering Officer, also signed by Sam C. Adams. Filled in Portland, September 2, 1864. Folds at center with bright and clean, well printed upon white wove period paper, having full margins, and a sharp embossed official seal at the upper left.

William O. Freeman, of Saco, York County, Maine was a Republican, later the Mayor of Saco, Maine in 1902. We believe he was a Substitute of a previously enlisted Navy Sailor who decided not to fight and instead hired a Substitute to take his place in the War. This is a Very Rare form, as citizens were not drafted into the Navy, but rather they enlisted. This was opposed to the Army where you were simply drafted.

Taken from 'thecivilwaromnibus.com':

When the Civil War began, there was no shortage of able bodied men who volunteered for service in both the U.S. Army and the Confederate Army.When the draft laws - known as the Enrollment Act - were first placed on the books in the United States in 1863, they allowed for two methods for avoiding the Draft - "Substitution" or "Commutation."

A man who found his name called in the draft lotteries that chose men for mandatory service could either pay a Commutation fee of $300, which exempted him from service during this draft lottery, but not necessarily for future draft lotteries, or he could provide a substitute, which would exempt him from service throughout the duration of the war.

The $300 Commutation fee was an enormous sum of money for most city laborers or rural farmers, and the cost of hiring a Substitute was even higher, often reaching $1,000 or more. The practice of hiring substitutes for military service took hold quickly in the North, becoming much more widespread than it had ever been in the South. For one thing, there was a much larger pool of men to draw from; immigrants that flowed into the ports of the North, even in a time of war, provided a large number of the substitutes hired by those who did not wish to serve.

As the duration of the war lengthened, African-American soldiers, who'd thus far been only nominally accepted by the U.S. Army as viable soldiers, also became part of the pool of potential substitutes. Many of the recruitment posters from the time explicitly solicit African-Americans for substitution. Although the hiring of substitutes seems mercenary, and in many cases, resulted in the desertion of the substitute, many who went to war as hired men went because they were unable to enlist through the regular channels. This included the recent immigrants who were anxious to fight for their new country, and, importantly, the African-Americans who found going to war as substitutes the only way to fight for their freedom. For these men, the war was indeed a "rich man's war and a poor man's fight," but from the perspective that poor men were more willing to fight for the possibilities they saw in their country.

- Shipping Info

-

Early American provides in-house worldwide shipping. Please contact us directly if you have questions about your specific shipping requirements.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB