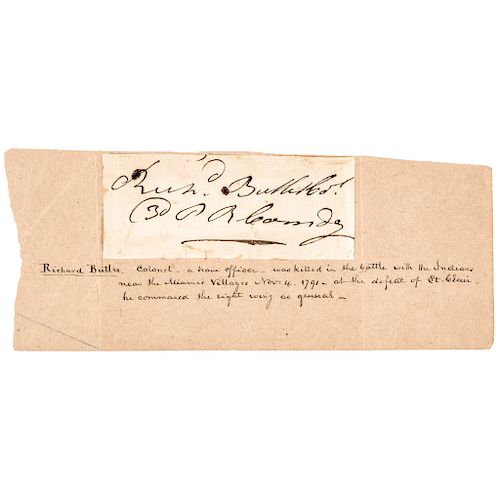

Major General RICHARD BUTLER Killed while Fighting Indians at St. Clair's Defeat

Lot 18

Categories

Estimate:

$400 - $600

Absentee vs Live bid

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $10 |

| $200 | $20 |

| $300 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $200 |

| $3,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,000 |

| $30,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

| $200,000 | $20,000 |

| $300,000 | $25,000 |

| $500,000 | $50,000 |

About Auction

By Early American History Auctions

Oct 19, 2019

Set Reminder

2019-10-19 12:00:00

2019-10-19 12:00:00

America/New_York

Bidsquare

Bidsquare : Historic Autographs-Currency-Political-Americana-Militaria-Guns

https://www.bidsquare.com/auctions/early-american-history-auctions/historic-autographs-currency-political-americana-militaria-guns-4513

326 Lots of Rare, Historic Autographs, Americana, Civil War Era, George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, Black History, Revolutionary War Era, Colonial America, Federal Period, War of 1812, Colonial Currency, Indian Peace Medals & more... Early American History Auctions auctions@earlyamerican.com

326 Lots of Rare, Historic Autographs, Americana, Civil War Era, George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, Black History, Revolutionary War Era, Colonial America, Federal Period, War of 1812, Colonial Currency, Indian Peace Medals & more... Early American History Auctions auctions@earlyamerican.com

- Lot Description

Autographs

Major General Richard Butler Signature Revolutionary War Officer Killed at "St. Clair's Defeat"

RICHARD BUTLER (1743-1791). Revolutionary War Major General, Killed while Fighting Indians at "St. Clair's Defeat," known as "the most decisive defeat in the history of the American military."

c. 1777 Revolutionary War Period, Outstanding Large Clipped Signature, "Ricd. Butler Col / 3d PA Comdg.", 4.5" x 2" mounted to a 8.75" x 3.5" album page, Choice Very Fine. An original and rare autograph, he was a Pennsylvania frontiersman and Indian trader who served as a Major General in the American Revolution. He negotiated with the Indians as a commissioner of the Continental Congress, and fought with Morgan's Riflemen at Saratoga and Monmouth, and with Anthony Wayne at Stony Point and Yorktown. He was later killed in battle with the Miami Indians at St. Clair's defeat in the Northwest Territory 1791, A nice strong signature. Notes below signature read: "Richard Butler. Colonel... a brave officer - was killed in the battle with the Indians near the Miami Villages Nov 4, 1791 - at the Defeat of St. Clair - he commanded the right wing as General." An extremely rare Revolutionary War period signature that is large, boldly written and impressive for display. The very first we have offered.

At the outset of the American Revolution, the Continental Congress named Richard Butler a commissioner in 1775 to negotiate with the Indians. He visited representatives of the Delaware, Shawnee, and other tribes to secure their support, or at least neutrality, in the war with Britain.

On July 20, 1776, Butler was commissioned a major in the 8th Pennsylvania Regiment in the Continental Army, serving first as second in command to his friend Daniel Morgan. He was promoted to lieutenant colonel in March 12, 1777 retroactive to September 1776. On June 7, 1777 he was promoted to colonel and placed in command of 9th Pennsylvania Regiment.

During the war he saw action at the Battle of Saratoga (1777) and the Battle of Monmouth (1778). His four other brothers also served, and were noted for their bravery as the "fighting Butlers".

In January 1781 he was transferred to the 5th Pennsylvania and lead the Continental Army at the Battle of Spencer's Ordinary.

At the conclusion of the Battle of Yorktown in October 1781, General George Washington conferred on Richard Butler the honor of receiving Cornwallis' sword of surrender, an honor which Richard gave to his second in command, Ebenezer Denny. At the last moment, Baron von Steuben demanded that he receive the sword. This almost precipitated a duel between Butler and Von Steuben.

At the victory dinner for his officers, George Washington raised his glass and toasted, "The Butlers and their five sons!"

Following Yorktown, Butler remained in the Continental Army and was transferred to the 3rd Pennsylvania following a consolidation of the Army on January 1, 1783. On September 30th of the same year, he was breveted (i.e. an honorary promotion) as a brigadier general. Butler remained in active service with the Continental Army until it was finally disbanded on November 3, 1783.

After the war, the Confederation Congress put Richard Butler in charge of Indians of the Northwest Territory. He negotiated the Treaty of Fort Stanwix in 1784, in which the Iroquois surrendered their lands. He was also called upon during later negotiations, such as the Treaty of Fort McIntosh in 1785.

Butler returned to Pennsylvania, and was a judge in Allegheny County. He also served in the state legislature. He married Maria Smith and had four children, only one of whom lived to have children and continue the line. Butler also fathered a son, Captain Butler (or Tamanatha) with Shawnee chief Nonhelema. Butler and his Shawnee son fought in opposing armies in 1791.

In 1791, Butler was commissioned a major general in the levies (i.e. militiamen conscripted into Federal service) under Major General Arthur St. Clair to fight against the Western Confederacy of Native Americans in the Northwest Territories (modern day Ohio). He was killed in action on November 4, 1791 in St. Clair's Defeat at what is now Fort Recovery, Ohio.

Reportedly he was first buried on the battlefield, which site was then lost until it was accidentally found years later. The remains were laid to rest with the remains of the other fallen at Fort Recovery.

In 1783 Butler became an Original Member of the Pennsylvania Society of the Cincinnati, a military society of officers who had served in the Continental Army.

St. Clair's Defeat, also known as the Battle of the Wabash, the Battle of Wabash River, or the Battle of a Thousand Slain, was a battle fought on November 4, 1791 in the Northwest Territory of the United States. The U.S. Army faced the Western Confederacy of American Indians, as part of the Northwest Indian War. It was "the most decisive defeat in the history of the American military." It was the largest victory ever won by American Indians.

The American Indians were led by Little Turtle of the Miamis, Blue Jacket of the Shawnees and Buckongahelas of the Delawares (Lenape). The war party numbered more than one thousand warriors, including a large number of Potawatomis from eastern Michigan and the Saint Joseph. The opposing force of about 1,000 Americans was led by General Arthur St. Clair. The forces of the American Indian confederacy attacked at dawn, taking St. Clair's men by surprise.

Of the 1,000 officers and men that St. Clair led into battle, only 24 escaped unharmed. As a result, President George Washington forced St. Clair to resign his post and Congress initiated its first investigation of the executive branch.

On the evening of 3 November, St. Clair's force established a camp on a high hill near the present-day location of Fort Recovery, Ohio, near the headwaters of the Wabash River.

An Indian force consisting of around 1,000 warriors, led by Little Turtle and Blue Jacket, waited in the woods until dawn, when the men stacked their weapons and paraded to their morning meals. Adjutant General Winthrop Sargent had just reprimanded the militia for failing to conduct reconnaissance patrols when the natives then struck, surprising the Americans and overrunning their ground.

Little Turtle directed the first attack at the militia, who fled across a stream without their weapons. The regulars immediately broke their musket stacks, formed battle lines and fired a volley into the Indians, forcing them back. Little Turtle responded by flanking the regulars and closing in on them. Meanwhile, St. Clair's artillery was stationed on a nearby bluff and was wheeling into position when the gun crews were killed by Indian marksmen, and the survivors were forced to spike their guns.

Colonel William Darke ordered his battalion to fix bayonets and charge the main Indian position. Little Turtle's forces gave way and retreated to the woods, only to encircle Darke's battalion and destroy it. The bayonet charge was tried numerous times with similar results and the U.S. forces eventually collapsed in disorder. St. Clair had three horses shot out from under him as he tried in vain to rally his men.

After three hours of fighting, St. Clair called together the remaining officers and, faced with total annihilation, decided to attempt one last bayonet charge to get through the Indian line and escape. Supplies and wounded were left in camp. As before, Little Turtle's Army allowed the bayonets to pass through, but this time the men ran for Fort Jefferson. They were pursued by Indians for about three miles before the latter broke off pursuit and returned to loot the camp. Exact numbers of wounded are not known, but it has been reported that execution fires burned for several days afterward.

The casualty rate was the highest percentage ever suffered by a United States Army unit and included St. Clair's second in command. Of the 52 officers engaged, 39 were killed and 7 wounded; around 88% of all officers became casualties. After two hours St. Clair ordered a retreat, which quickly turned into a rout. "It was, in fact, a flight," St. Clair described a few days later in a letter to the Secretary of War. The American casualty rate, among the soldiers, was 97.4 percent, including 632 of 920 killed (69%) and 264 wounded. Nearly all of the 200 camp followers were slaughtered, for a total of 832 Americans killed.

Approximately one-quarter of the entire U.S. Army had been wiped out. Only 24 of the 920 officers and men engaged came out of it unscathed, the survivors included Benjamin Van Cleve and his uncle Robert Benham; Benjamin was one the few who were unharmed. Indian casualties were about 61, with at least 21 killed.

The number of U.S. soldiers killed during this engagement was more than three times the number the Sioux would kill 85 years later at the Battle of Little Big Horn. The next day the remnants of the force arrived at the nearest U.S. outpost, Fort Jefferson, and from there returned to Fort Washington

- Shipping Info

-

Early American provides in-house worldwide shipping. Please contact us directly if you have questions about your specific shipping requirements.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB