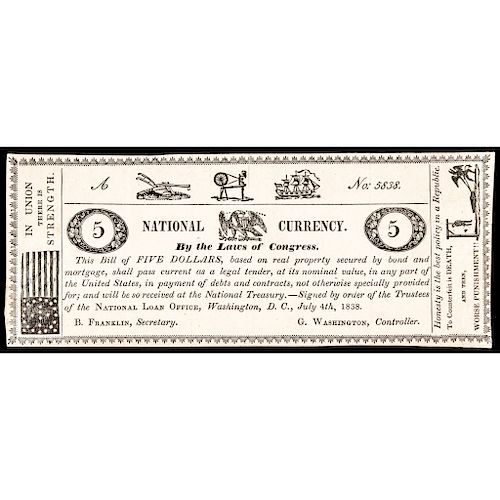

July 4, 1838 National Currency Note Illustration + B. FRANKLIN + G. WASHINGTON

Lot 218

Estimate:

$800 - $1,000

Absentee vs Live bid

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $10 |

| $200 | $20 |

| $300 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $200 |

| $3,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,000 |

| $30,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

| $200,000 | $20,000 |

| $300,000 | $25,000 |

| $500,000 | $50,000 |

About Auction

By Early American History Auctions

Jul 13, 2019

Set Reminder

2019-07-13 12:00:00

2019-07-13 12:00:00

America/New_York

Bidsquare

Bidsquare : Colonial & Continental Currency-Coinage-Historic Peace Medals- Encased Postage Stamps

https://www.bidsquare.com/auctions/early-american-history-auctions/colonial-continental-currency-coinage-historic-peace-medals--encased-postage-stamps-4256

Historic Coins, Colonial & Continental Currency, Political, Americana, Encased Postage Stamps, Peace Medals Early American History Auctions auctions@earlyamerican.com

Historic Coins, Colonial & Continental Currency, Political, Americana, Encased Postage Stamps, Peace Medals Early American History Auctions auctions@earlyamerican.com

- Lot Description

Obsolete Currency

July 4, 1838 Proposed National Currency Note Illustration

July 4, 1838-Dated Printed Note Illustration, Washington, D.C., "NATIONAL CURRENCY by the Laws of Congress," Five Dollars, "B. FRANKLIN, Secretary - G. WASHINGTON, Controller," Choice Extremely Fine.

Haxby-Not listed. Exceedingly Rare, Printed United States Proposed National Currency Note Illustration, proposed to be issued by the Federal government, the first we have offered. Printed in black on period wove paper titled "NATIONAL CURRENCY" with a decorative border design and wonderful 26-Star American Flag design with logo "IN UNION there is STRENGTH" within the left margin, blank reverse is very clean with light folds. The right side margin vignette with a Hanging Man at the gallows, a casket below reading in part, "To Counterfeit is DEATH and then, WORSE PUNISHMENT" in criticism of our Currency! Its design was included in a pamphlet proposal in 1834 written by Thomas Mendenhall. See: Russ Rulau's "Standard Catalog of United States Tokens, 1700-1900" and Stack's John J. Ford, Jr. Collection Sale. An exceptional, high quality specimen that would prove an important addition to any Banking History and United States Paper Money collection.

The Panic of 1837 was a financial crisis in the United States that touched off a major recession that lasted until the mid-1840s. Profits, prices, and wages went down while unemployment went up. Pessimism abounded during the time. The panic had both domestic and foreign origins. Speculative lending practices in western states, a sharp decline in cotton prices, a collapsing land bubble, international specie flows, and restrictive lending policies in Great Britain were all to blame.

Mendenhall, Thomas. An Entire New Plan for a National Currency: Suited to the Demands of this Great, Improving, Agricultural, Manufacturing & Commercial Republic, with Appropriate

Introductory and Concluding Remarks. To Which Is Added, A Plan for a Real National Bank. Philadelphia: J. Rakestraw, 1834, 32 pp., with sample of a $5 issue of national currency tipped in. Disbound but preserving original plain brown wrappers.

It is not entirely clear who Thomas Mendenhall was. In this pamphlet he mentions in passing that, during the revolution, he "experienced several times, the misfortune of capture and plunder at sea; and ... suffered the horrors of starvation, and other miseries of a British prison ship at New York." He also indicates that he first issued his currency proposal in 1816. In his American Radicalism, 1865-1901, Chester M. Destler identifies this as a pamphlet entitled National Money, or a simple System of Finance; [etc.] (Georgetown, Va., 1816).

Here he elaborates on his earlier proposal and sets out a specific draft statute for creation of a national currency (pp. 17-20). He was well aware of Thomas Law's advocacy of a national currency and calls Law a "respectable writer." But he implies that Law's proposals have lacked specificity. He also sets out specific statutory language (pp. 27-29) for creation of a national bank "founded upon the credit of the Government and its resources," as Andrew Jackson had suggested might be possible in his annual message of 1829.

The national currency would be issued by a National Loan Office and would be a legal tender. The National Loan Office would lend the currency to State Loan Offices at either 4 or 5 percent per annum. The State Loan Offices would in turn lend the currency to individuals at either 5 or 6 percent per annum. The loans to individuals would be secured by land and mortgages on real property, worth double (or at least one third more) than the amount of the loan. Interest on the loans to individuals would be payable annually or semi-annually. As long as the borrower made the interest payments, repayments of principal would be "at the convenience of the borrower." The National Loan Office might also make loans to the states, which they could use to finance internal improvements or to pay down existing debts. Finally, the might authorize the National Loan Office to lend money to the federal government.

Mendenhall anticipates concerns that the national currency might depreciate. He argues that this can't happen because of the security provided for the loans (focusing on the loans to the individual and ignoring his proposals to make loans to the states and to the national government). As he puts it, "the real value of the land is made to pass into the nominal value of the money." With respect to the loans to the national and state government, if such loans "bring a redundant quantity of the currency into circulation, and cause an injurious rise in the prices of specie ... , which might erroneously be supposed a depreciation of the currency; it would, in such case, be the duty of the Government and the State Legislatures, to provide ways and means for drawing such redundance out of circulation ..."

He argues that his national currency would be far superior to a currency ostensibly payable in specie. He notes that a specie currency is vulnerable to an export of specie and observes that existing banks cannot really redeem in specie because the amount of specie that they hold in their vaults is generally a very small fraction of their notes outstanding. He believes that the issuance of national currency under his plan will put to rest "the old and delusive dogma, that a specie basis is indispensable in all Banks of Discount and Deposit."

Destler concludes that Edward Kellogg (see 1849) drew on Mendenhall for his influential currency plan and for his critique of the Safety Fund System. As will be discussed in connection with Kellogg's works, Kellogg was known as the father of Greenbackism.

Also of note, the sample of national currency that is tipped in is quite charming. It resembles contemporary bank notes but instead of being issued under the names of a bank president and cashier it is issued under the names of G. Washington, Controller, and B. Franklin, Secretary, of the National Loan Office.

On May 10, 1837, banks in New York City suspended specie payments, meaning that they would no longer redeem commercial paper in specie at full face value.

Despite a brief recovery in 1838, the recession persisted for approximately seven years. Banks collapsed, businesses failed, prices declined, and thousands of workers lost their jobs. Unemployment may have been as high as 25% in some locales. The years 1837 to 1844 were, generally speaking, years of deflation in wages and prices.

- Shipping Info

-

Early American provides in-house worldwide shipping. Please contact us directly if you have questions about your specific shipping requirements.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB