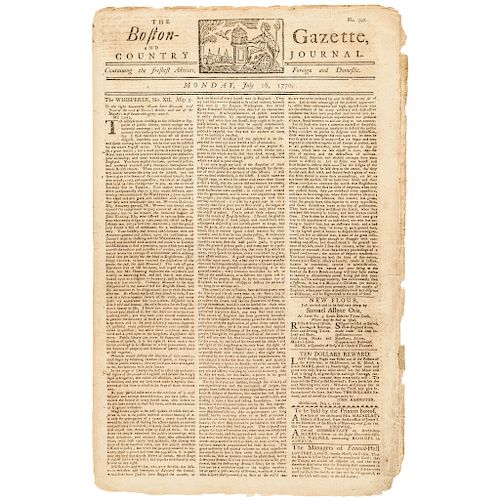

July 1770 Paul Revere Masthead Boston Gazette Newspaper and Boston Massacre News

Lot 135

Estimate:

$1,600 - $2,400

Absentee vs Live bid

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $10 |

| $200 | $20 |

| $300 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $200 |

| $3,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,000 |

| $30,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

| $200,000 | $20,000 |

| $300,000 | $25,000 |

| $500,000 | $50,000 |

About Auction

By Early American History Auctions

Aug 24, 2019

Set Reminder

2019-08-24 12:00:00

2019-08-24 12:00:00

America/New_York

Bidsquare

Bidsquare : Autographs, Colonial Currency, Political Americana, Historic Guns

https://www.bidsquare.com/auctions/early-american-history-auctions/autographs-colonial-currency-political-americana-historic-guns-4347

Historic Autographs • Colonial Currency • American Civil War Colonial Era • Revolutionary War • Political Americana • Black History Early American History Auctions auctions@earlyamerican.com

Historic Autographs • Colonial Currency • American Civil War Colonial Era • Revolutionary War • Political Americana • Black History Early American History Auctions auctions@earlyamerican.com

- Lot Description

American Revolution

July 16, 1770 Paul Revere Masthead Newspaper Four Months Post "Boston Massacre" in "The Boston Gazette"

July 16, 1770-Dated Colonial America, "The Boston Gazette and Country Journal", Four Months Post "Boston Massacre" Detailed Tensions between Acting Governor Hutchinson and the Colonial Assembly, Choice Extremely Fine.

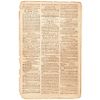

This original "The Boston Gazette and Country Journal" issue measures about 10" x 15.25", has 4 pages cleanly separated at the spine and reinforced with hidden clear tape inside, disbound, Complete. Articles detailing tensions between acting Governor Thomas Hutchinson and the Colonial Assembly, which reads in part:

Page 2, column 1 reports: "short account of the dispute between the Governor and Assembly, at Boston" (Regarding the "Boston Massacre of March 5, 1770."):

"Since Hutchinson's administration, happen'd the massacre of sundry persons in Boston by the soldiery, which occasioned their removal from the town, so that the objection against the assembly's doing business there was removed. Notwithstanding this, the lieutenant governor called the assembly to meet at Cambridge, informing them that for so doing he had his Majesty's express command. The council and house of representatives have each repeatedly remonstrated against this innovation. They have shewn, that by charter and acts of assembly confirm'd by the King, they have a right to meet at Boston, where convenient buildings are erected for that purpose, and where records are kept..." Also, "Public liberty can never be supported without freedom of speech, it is the right of every man; this Sacred priviledge is so essential to a free government , that the Security of property and freedom of speech, will stand of fall together." The lower right corner contains a notice regarding the upcoming "Faneuil-Hall LOTTERY"! A great, historical Boston newspaper of the period with a gorgeous, sharp Paul Revere Engraved Masthead at top. Fresh and clean overall, with a crisp sharply printed appearance.

Also includes an extensive essay by "The Whisperer" indicting Lord Mansfield, plus numerous notices and advertisements and much, much more period news, letters and historical information.

The Boston Massacre was a street fight that occurred on March 5, 1770, between a "patriot" mob, throwing snowballs, stones, and sticks, and a squad of British soldiers. Several colonists were killed and this led to a campaign by speech-writers to rouse the ire of the citizenry. All victims of the Massacre, Crispus Attucks, Samuel Gray, James Caldwell, Samuel Maverick and Patrick Carr, were buried at Granary Burying Ground in Boston.

What began as a street brawl between American colonists and a lone British soldier, but quickly escalated to a chaotic, bloody slaughter. The conflict energized anti-Britain sentiment and paved the way for the American Revolution.

Tensions ran high in Boston in early 1770. As more than 2,000 British soldiers occupied the city of 16,000 colonists and tried to enforce Britain's tax laws, American colonists rebelled against the taxes they found repressive, rallying around the cry, "no taxation without representation."

Skirmishes between colonists and soldiers - and between patriot colonists and colonists loyal to Britain (loyalists) - were increasingly common. To protest taxes, patriots often vandalized stores selling British goods and intimidated store merchants and their customers.

On February 22, a mob of patriots attacked a known loyalist's store. Customs officer Ebenezer Richardson lived near the store and tried to break up the rock-pelting crowd by firing his gun through the window of his home. His gunfire struck and killed an 11-year-old boy named Christopher Seider and further enraged the patriots.

Several days later, a fight broke out between local workers and British soldiers. It ended without serious bloodshed but helped set the stage for the bloody incident yet to come.

On the frigid, snowy evening of March 5, 1770, Private Hugh White was the only soldier guarding the King's money stored inside the Custom House on King Street. It wasn't long before angry colonists joined him and insulted him and threatened violence.

At some point, White fought back and struck a colonist with his bayonet. In retaliation, the colonists pelted him with snowballs, ice and stones. Bells started ringing throughout the town - usually a warning of fire - sending a mass of male colonists into the streets. As the assault on White continued, he eventually fell and called for reinforcements.

In response to White's plea and fearing mass riots and the loss of the King's money, Captain Thomas Preston arrived on the scene with several soldiers and took up a defensive position in front of the Custom House.

Worried that bloodshed was inevitable, some colonists reportedly pleaded with the soldiers to hold their fire as others dared them to shoot. Preston later reported a colonist told him the protestors planned to "carry off [White] from his post and probably murder him."

The violence escalated, and the colonists struck the soldiers with clubs and sticks. Reports differ of exactly what happened next, but after someone supposedly said the word "fire," a soldier fired his gun, although it's unclear if the discharge was intentional.

Within hours, Preston and his soldiers were arrested and jailed and the propaganda machine was in full force on both sides of the conflict.

Preston wrote his version of the events from his jail cell for publication, while Sons of Liberty leaders such as John Hancock and Samuel Adams incited colonists to keep fighting the British. As tensions rose, British troops retreated from Boston to Fort William.

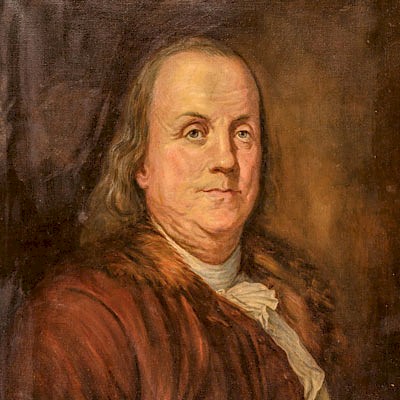

Paul Revere encouraged anti-British attitudes by etching a now-famous engraving depicting British soldiers callously murdering American colonists. It showed the British as the instigators though the colonists had started the fight.

It also portrayed the soldiers as vicious men and the colonists as gentlemen. It was later determined that Revere had copied his engraving from one made by Boston artist Henry Pelham.

- Shipping Info

-

Early American provides in-house worldwide shipping. Please contact us directly if you have questions about your specific shipping requirements.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB