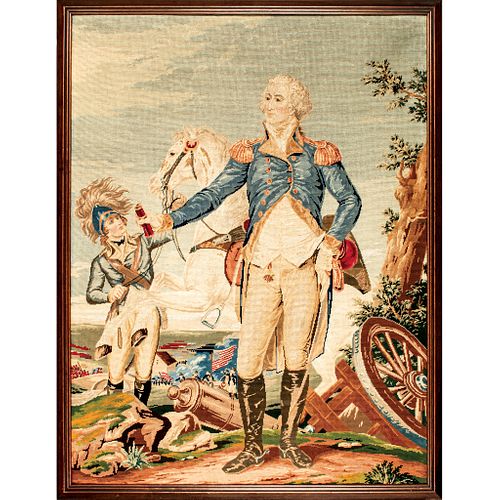

c. 1840 George Washington at Trenton, Berlin Wool Work Portrait 33 w x 44 h

Lot 263

Categories

Estimate:

$2,400 - $2,800

Absentee vs Live bid

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $10 |

| $200 | $20 |

| $300 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $200 |

| $3,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,000 |

| $30,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

| $200,000 | $20,000 |

| $300,000 | $25,000 |

| $500,000 | $50,000 |

About Auction

By Early American History Auctions

Aug 21, 2021

Set Reminder

2021-08-21 12:00:00

2021-08-21 12:00:00

America/New_York

Bidsquare

Bidsquare : Autographs - Historic & Political Americana - Militaria & Guns

https://www.bidsquare.com/auctions/early-american-history-auctions/autographs---historic-political-americana---militaria-guns-7321

335 Lots of Rare, Historic Autographs, Americana, Civil War Era, George Washington, Revolutionary War Era, Colonial America, Federal Period, War of 1812, Colonial Currency & more... Early American History Auctions auctions@earlyamerican.com

335 Lots of Rare, Historic Autographs, Americana, Civil War Era, George Washington, Revolutionary War Era, Colonial America, Federal Period, War of 1812, Colonial Currency & more... Early American History Auctions auctions@earlyamerican.com

- Lot Description

Historic Americana

"George Washington at Trenton" Berlin Wool Work Textile After the Oil Painting by John Trumbull Similar to Specimen Illustrated on the Dust Jacket Cover of "Threads of History"

c. 1850, Impressive Hand-Stitched "George Washington at Trenton", Mammoth 33" wide x 44" tall Berlin Wool Work Portrait, After the Painting by John Trumbull, Extremely Fine.

c. 1850 Large Colorful Berlin Wool Work with a historic standing Portrait of General George Washington. Measuring about 33" x 44", this embroidered portrait takes after John Trumbell's oil painting "General George Washington at Trenton". This Wool Work textile is listed in "Threads of History" by Herbert Ridgeway Collins as #221 on page 132 and also takes prominence on the jacket cover of Collins' book. This portrait is framed in a simple stained wood without glass, backed for support on heavy card. Its multitude of colors appear to be as virtually as rich as when it was first worked. This image of "General George Washington at Trenton" is after a large full-length portrait in oil painted in 1792 by the American artist John Trumbull of General George Washington at Trenton, New Jersey, on the night of January 2, 1777, during the American Revolutionary War. This is the largest size "George Washington at Trenton" Berlin Wool Work Textile we have offered.

Berlin Wool Work, as we know it today, was developed in Germany in the 19th century for the amateur stitcher, based on Hand-painted charts of Cross Stitch patterns, that were worked with a very soft wool that was spun in the city of Saxe-Gotha, located in the central German region. The wool was taken to Berlin, where it was dyed and packaged with the charts which were also printed and painted there.

The first charts were released in 1804, and within the next forty years, at least 14,000 different designs were produced. When the brightly-colored wools became commercially available in 1820, it was accorded the name Berlin Work; these wools actually began to replace crewel, lambswool and silk threads that had been popular materials.

The wool was dye in brilliant colors reflecting popular German taste. In addition to the standard Cross and Tent Stitches, a new stitch called the Surrey Stitch, created a thick dimensional pile that added to the richness and reality of floral designs. As if this were not enough, some designs even called for the inclusion of colored glass beads as accent.

In 1810, a Madame Wittich of Berlin decided that better charts were needed, and she tried to interest local artists in this endeavor. The result was not only improved charts, but a return to better materials like silk and a higher grade of canvas. Herr Wittich saw the commercial value of charts that were copies of classic or popular paintings with the colors actually painted on the canvas in the squares. Artists were hired to transfer great works of art onto canvas, and encouraged to create their own floral and geometric designs. Some of these original designs were created on "point" paper and were very expensive. ("Point" paper is graph paper using 1 square = 1 inch scale.)

One of the special characteristics of Berlin Work patterns was the use of "point" paper that showed colored blocks on the paper that corresponded to the squares on the canvas. Before this, colors had been indicated by codes and patterns were printed using copper plates; the printed pattern then had to be graphed and painted by hand, which added to the cost.

The embroiderer could now follow a colored graph by counting lines, squares, and stitches on a blank canvas. A new canvas was created that had parallel threads crossing at larger intervals, and that innovation was followed by the inclusion of a blue line placed vertically at intervals of 5 or 10 threads to help the stitcher count.

Another important characteristic of Berlin Work was the type and quality of wool used. Until this time, old English and Netherlands wools, called zephers, were used in tapestries and worsted embroideries. The quality of this new wool fiber was much better and the way it accepted dye produced a much more satisfying product.

The wool was softer than crewel thread, which was wiry and twisty, and strands of woven crewel thread were very difficult to separate. Because the new wool product took dye so well, more brilliant colors could be produced. In addition, the weight of the Berlin wool was designed to fit the canvas. Berlin wool was manufactured for knitting as well as embroidery.

Some German wool was brought to England in its raw state, then combed, spun and dyed in Scotland. To quote Caulfeild, "that dyed here is less perfect and durable than that imported ready for use, except those dyed in black which are cleaner in working." (Caulfeild 27). Eventually, Berlin wool was produced in Yorkshire by blending German and English wool. However, it is interesting to note that although the traditionally dynamic colors were popular with German embroiderers, English needlewomen appear to have preferred softer and more subtle colors.

Prior to 1830, Berlin Work patterns were not well known outside of Germany. German stitchers worked the patterns and some even earned small sums of money by selling their finished products. In 1831, a Mr. Wilks of Regent Street in London purchased as many good designs as he could find, as well as the patterns and working materials from Berlin and Paris. By the middle of the 19th century, Berlin Work patterns had become the favorite designs of embroiderers in both England and the United States.

In 1870, the rise of the Art and Crafts Movement in England, led by the brilliant designer William Morris and later picked up in New England, spelled the decline in popularity of Berlin Work.

- Shipping Info

-

Early American provides in-house worldwide shipping. Please contact us directly if you have questions about your specific shipping requirements.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB